Every now and again, you don’t have to think hard to find a story to tell in the weekly column because something just lands in your lap, so to speak.

The main topic last week was tomato growing, so the other day I was accosted by a chap who had been growing tomatoes in his greenhouse for years without much bother.

This year, however, there’s something nae right wi ’them.

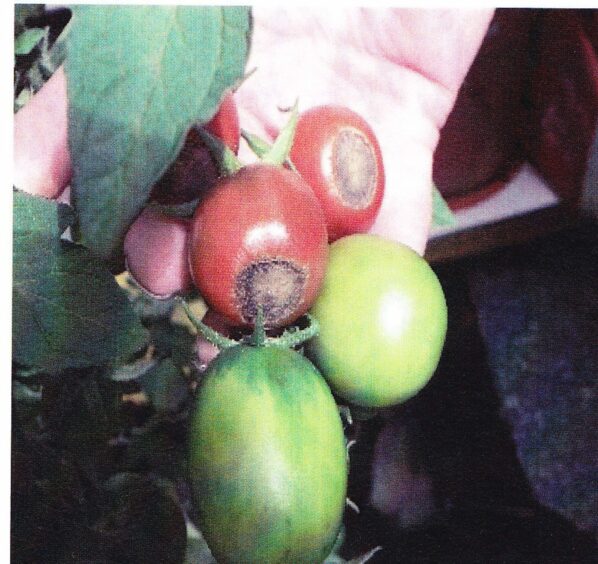

His tomatoes were showing the classic signs of blotchy ripening.

When looking for confirmation of a diagnosis, I always turn to my bible on Tomato Fruit Quality, written back in 1973 by a colleague in the Agricultural Development and Advisory Service (ADAS) of England and Wales for which I was working at the time.

The second half of our growing season brings up problems every year and this is no exception.

Whilst some of these occurrences are due to our own fallibility, much is due to seasonal weather patterns.

Blotchy ripening – the reasons

So, what’s the reason for blotchy ripening of tomatoes?

Let me quote directly from the ‘bible’ on the subject.

“As the fruit ripens, patches of the surface skin remain green or yellow.

“These patches may be well defined or may merge into the normally coloured areas.

“In extreme cases, large areas of the fruit surface have a glassy look. This problem may be confined to the lower fruit trusses and it is then generally more common on large fruited varieties.

High temperatures

“There is also strong evidence that excessively high temperatures in summer will increase the amount of blotchy ripening, especially when fruit is exposed to direct sunlight.

“In summing up, the disorder is most common on vigorous crops growing in conditions of low soluble salt levels, particularly potassium, low (night) temperatures or overwatering.

“Lower trusses are susceptible because, as experienced growers will know it is customary to start removing lower leaves to allow more light in to aid the ripening of the lower trusses.”

In so doing, there is a danger that some fruits may be affected by blotchy ripening so ca’ canny with that job.

Avoiding the problem

All of each fruit is not affected and once the ‘bad’ bit has been removed, the rest of the fruit is perfectly edible.

That, however, leaves a feeling of dissatisfaction; surely it must be possible to avoid the problem in the first place. Absolutely correct.

Firstly, amateur glasshouses are notoriously poorly ventilated and as a result, daytime temperatures can soar into very high levels BUT, foliage and fruit quality is adversely affected as soon as temperatures rise above the mid-80s F.

To cool the place down AFTER the ventilators have opened to their maximum, it may be necessary to leave the door open.

I appreciate that that is a difficult situation where marauding cats, rabbits and birds may take advantage when you are not there.

The answer is fit a net screen door.

Direct sunlight

Secondly, there is the problem of the high fruit temperatures being caused by direct sunlight, sunburn in other words.

There are two solutions to that, one cultural the other mechanical.

Whilst de-leafing is a common practice to allow air to circulate more freely round the ripening fruits and in so doing, cut down the incidence of grey mould fungus attack, over-zealousness will expose fruits to the direct rays of the sun.

In other words, do continue to de-leaf but ca’ canny.

You may also choose to shade the greenhouse surfaces.

In the old days we used whitewash with a dash of linseed oil mixed in, to make it stick (which was a real problem to clean off).

Nowadays there are proprietary products available such as Coolglass.

I wouldn’t want to dissuade you from that practice but the trouble is the perverseness of nature itself.

No sooner will you have it applied than you won’t see the sun again for several weeks leading to poor setting of later trusses because of low light intensity.

Roller blinds? Ideal for the job but a) you have to be in attendance to work them and b) you may consider that to be an expensive indulgence.

Finally we come to a much more contentious point, when and how to feed. That will depend on whether the plants are ‘in the ground’ or in containers like growbags.

A typical recommendation reads like this: “If growing in the soil, when first truss of tomatoes has set, feed at alternate waterings. When using growbags, feed once per week and increase to twice per week after the second truss has set. In each case, using a standard liquid feed as instructed.”

Experimentation

There is room here for a little bit of experimentation because there are so many different ways of growing tomatoes under glass.

My advice is to feed regularly. Strangely enough, this may slow down the growth but improve the quality and as a result improve the quality of the fruit AND its flavour too.

Conversation