To watch the relationship between Karen Adam and her father, Leonard Mellis, is to see a beautiful bond unfold.

Able to finish one another’s sentences, the pair converse with ease.

The fact they are so in tune should not be particularly surprising, bar the fact that Karen has rarely heard her father speak.

Rather than focus on what some might perceive as silence, the pair have developed a deeper form of communication over the passing years.

Every expression and every feeling perfectly captured, rather than lost in a tangle of conversation.

We converse via BSL, and my dad told me how both himself and his friends suffered trauma because of their school years

Karen has acted as a CODA for Leonard from a young age, enabling him to connect with the many aspects of society – where British Sign Language (BSL) is not widely known.

Leonard, 73, was born Deaf, and has gone on to use BSL throughout life – although its use was frowned upon during his childhood.

From finding love to having a successful career in an optician, deafness does not define Leonard as a person.

But that does not mean to say that life has been easy, and Scotland is so far the only country in the UK that has given BSL recognition in law.

My dad has never seen it as a disability, it is society that sees it as a fault in him

The BSL (Scotland) Act 2015 made it a legal requirement for the Scottish Government and public bodies to promote, and facilitate the promotion of, the use and understanding of BSL.

International Day of Sign Languages

As we celebrate International Day of Sign Languages on September 23 alongside International Week of the Deaf, what does BSL mean to those who use it?

It is estimated that 151,000 people in the UK use British Sign Language, and that 87,000 of them are d/Deaf.

The word deaf is used to describe or identify anyone who has a severe hearing problem, whereas Deaf with a capital D refers to people who have been deaf all their lives, or since before they started to learn to talk.

What it is like to navigate the world as a BSL user, and what more needs to be done to make our society, and in turn our communities, as inclusive as possible?

We spoke to BSL users and interpreters to find out more.

Karen Adam MSP, and Leonard Mellis, BSL users

Mum-of-six Karen Adam has been an MSP for Banffshire and Buchan Coast since 2021.

She is determined to use her political platform to help enable real changes surrounding BSL, and has the ultimate vision of it becoming part of the school curriculum.

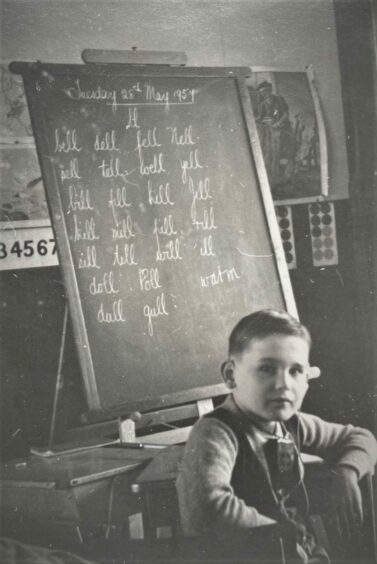

She is all too aware of the trauma which Leonard faced during childhood, when it was common for children to be physically punished if they attempted to sign.

Leonard was instead fitted with a cumbersome hearing aid, forced to undergo intense speech therapy, and smacked on the hands with a ruler if he was seen to be using BSL.

Trauma in school years

“I’ve very rarely heard my dad talk at all,” says Karen.

“We converse via BSL, and my dad told me how both himself and his friends suffered trauma because of their school years.

“They were treated in such a way to make them feel that they were less than, if they could not fit in with day-to-day life.

“His parents were told to talk to him, and he in return would use lip reading.

“Anything different was frowned upon; this was a time when children with additional needs were placed into homes.

“As I was growing up, I was able to see the joy that BSL could bring.

“It’s not just a way of communicating, it is a subset culture.”

Learning BSL in childhood

Karen has rarely known Leonard to use a hearing aid, and he takes immense pride in being part of the d/Deaf community.

“He has never seen it as a disability, it is society that sees it as a fault in him,” says Karen.

“BSL has always been part of my world.

“I think I finger spelled first. If I didn’t know a sign, then I would finger spell it out to dad and he in turn would teach me what the sign was.

“When I was younger I would go to the doctors or the bank with him, and act as his interpreter.”

Karen has even sat in the operating theatre whilst Leonard underwent a local anesthetic, and conversed with him via hand holding.

“My dad always had me as an interpreter, but lots of D/Deaf people don’t have anyone,” she said.

Discrimination within society

“We are really lacking with interpreters, and it shows when dealing with any kind of business.

“Phone companies for example, we were trying to sort a contract out and the company wanted to hear my dad on the telephone.

“We explained that he is Deaf, but still they insisted. They asked him to make a noise, a grunt.

“It was disgusting and so dehumanising.

“Any admin that comes with a strict security protocol, there is nothing in place for d/Deaf people.

“You need good internet for online interpreters.

“Sign language should be at the forefront of all organisations, third sector and public sector.

“But it is often forgotten.”

Get to grips with basics

Karen believes that even learning the basics, such as the BSL alphabet, can go a long way.

“I think there’s leftover remnants, telling of days gone by where you can be reluctant to interact with somebody who is different to you,” she said.

“Whereas a d/Deaf person could be overjoyed that you have tried to communicate, if you have gone out of your way.

“Learning the BSL alphabet can open up this whole new world.

“I would love to see BSL on the curriculum, particularly in primary school staring in P1, appearing alongside English.

“That’s the ultimate wish list.

“It would mean so many issues would be resolved, with the next generation automatically growing up knowing sign language.

“I hope we get to that stage, because so many people have said to me that they wish they knew how to sign.

“If they had leaned as children, it would be effortless.”

Leonard is in agreement, and was able to speak to Your Life with Karen acting as his interpreter via video.

Thanks to BSL, I feel free

To watch the connection between them is humbling, and Leonard is now a d/Deaf historian.

“In 1880, there was a ban on the use of sign language, which spread around the world,” says Leonard.

“The attitude was that speech was the best way to integrate into society.

“I went to Aberdeen School for the Deaf, but it was an oral school.”

Leonard can recall feeling forced to speak, and found written English increasingly difficult.

“Sign language is really all about body language,” he says.

“It’s your facial expressions, you are projecting your feelings.

“Thanks to BSL, I feel free.

“Not restricted like my school days, when I was forced to communicate in a way which didn’t feel natural.”

Global connection

Just as accents can vary depending on where you live, there are also regional differences in sign language.

“I grew up with Doric sign language, but you’d see differences if you were in Glasgow,” says Leonard.”

International sign however, has the power to unite people from around the world.

The internationally recognised signs bridge the gap between different languages, and Leonard has recently been able to help a Ukrainian refugee family as a result.

“I don’t know Ukrainian, but I could still work out the signs,” says Leonard.

“I’ve also become very good at reading facial expressions and body language.

“You can read a person alongside signing.”

Leonard believes that younger people who are d/Deaf are now integrating more into society, but he would like to see them still come together as a group.

Don’t infantalise d/Deaf people

“There shouldn’t be any disadvantage to being d/Deaf,” he says.

“If people see me signing, the general reaction is ‘wow’.

“A small amount of people feel sorry for me, and I hate that.

“I am a grown man, not a baby.

“But people infantalise me, which is really frustrating.

“There are d/Deaf people all over the world who have gone on to be vets, teachers, medics.

“I see it as a hearing deficit, supplemented with sign language.”

Rebecca Goodall, interpreter and vice-chair of Highland Deaf Children’s Society

Highland Deaf Children’s Society (HDCS) is run by a small but mighty committee of family members of d/Deaf children alongside professionals who work with d/Deaf people.

They provide much needed support and advice to families of deaf or partially hearing children across the Highlands, and have a monthly meet-up at Frankie and Lola’s in Inverness.

For interpreter and vice-chair of HDCS Rebecca Goodall, BSL can enable children to reach their full potential.

Rebecca, who lives in Inverness, was one of only 10 people across Scotland chosen to take part in a government-funded project called Building Bridges, which enabled her to become a fully qualified and registered interpreter.

She has been involved with HDCS for around 15 years, and believes teaching even the basics in schools would provide a solid foundation.

Passion for sign language

“It all started for me when I met a BSL user when I was around 14 years old,” says Rebecca.

“I realised I didn’t know how to communicate with them, and that was my lightbulb moment.

“I knew I needed to do something about it, so I got together with a group of friends and started to learn signs.”

Rebecca went on to become involved with The Deaf Communication Project, and was head hunted by the deaf-led charity Deaf Action.

“It was to cover an admin role, but it also meant I was using sign language,” says Rebecca.

“The vision for HDCS is to make BSL as accessible as possible, so it is available to everyone.

“The charity itself provides opportunities for d/Deaf children and their families to get together, to have fun, and to be comfortable with who they are regardless of how they communicate.

“If everyone had those basic communication tactics and basic sign language was taught in schools, you have a starting point should you meet a d/Deaf child, friend, etc.

“I think as with many things in life, people can get a bit anxious about doing the wrong thing.

“They have it in their mind’s eye that it’s going to be really difficult to communicate with a d/Deaf person.

“I see it from an interpreter perspective all the time.

“But what’s really nice is when people want to learn the signs for hello, thank you.

“It starts there.”

Sheena Robertson: Parenting after diagnosis

Sheena, who is chair of HDCS, has firsthand experience of the struggles which families can face.

Her daughter, 16-year-old Kylah, was one of only three children in the Highlands who was misdiagnosed at birth.

It was originally thought Kylah had speech delay, until she was finally diagnosed with moderate hearing loss when she was around four years old.

She now wears hearing aids and uses BSL when conversing with d/Deaf friends.

Sheena, who lives in Inverness and works at Raigmore as an orthopedic staff nurse, believes changes needs to be made both in schools and in people’s attitudes.

Deafness need not be a stumbling block

“Kylah lost out on so much before she was fitted with hearing aids, and she has finally caught up,” says Sheena.

“She is now studying Childhood Practice at UHI.

“I think people are very awkward towards anyone who is d/Deaf though.”

Better support needed

Kylah attended mainstream school which Sheena believes was “hell” for her, with assumptions that due to hearing aids, she could hear perfectly fine.

“That’s not the case at all, what Kylah hears is completely different,” says Sheena.

“People aren’t aware of the situation, and Covid has not helped matters with masks.

“It has been a real struggle.”

Kylah started attending Highland Deaf Children’s Society when she was four, after Sheena looked for support from parents with shared experiences.

“I would like people to be more aware, to give respect and understand,” she says.

“If Kylah doesn’t hear something, people will say ‘oh it doesn’t matter’.

“They need to learn to be more accepting.

“Kylah would have benefitted so much had BSL been on the school curriculum.

“It’s a language, a way of communicating.

“Kylah’s hearing loss hasn’t stopped her from achieving, and I would want any parent in a similar situation to know that.”

Conversation