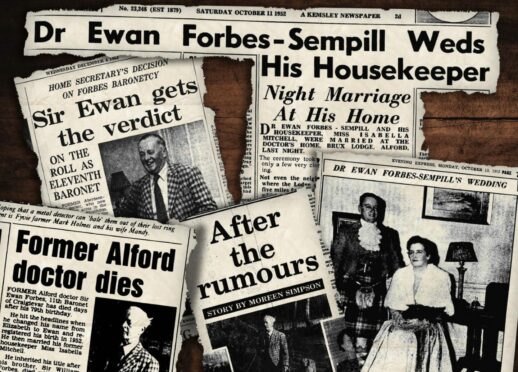

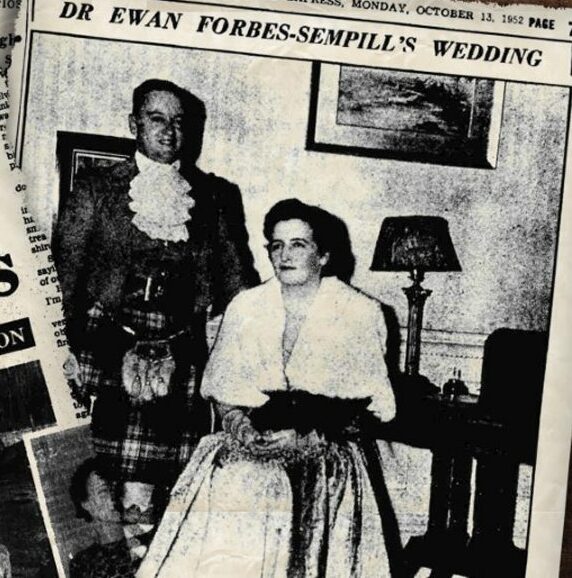

It’s a picture of marital bliss from 70 years ago; a celebration of the union of Dr Ewan Forbes-Sempill and Miss Isabella Mitchell which took place in palatial splendour at Brux Lodge in Kildrummy on October 10 1952.

The Press and Journal reported on how the couple and their guests enjoyed “an evening of song, recitation and dancing, to which the bridegroom contributed” and the occasion in Aberdeenshire was a happy one between two people who clearly loved each other.

Yet, although nobody knew it at the time, a torrent of controversy later engulfed Sir Ewan, which ended up in one of the most remarkable court cases of the 1960s.

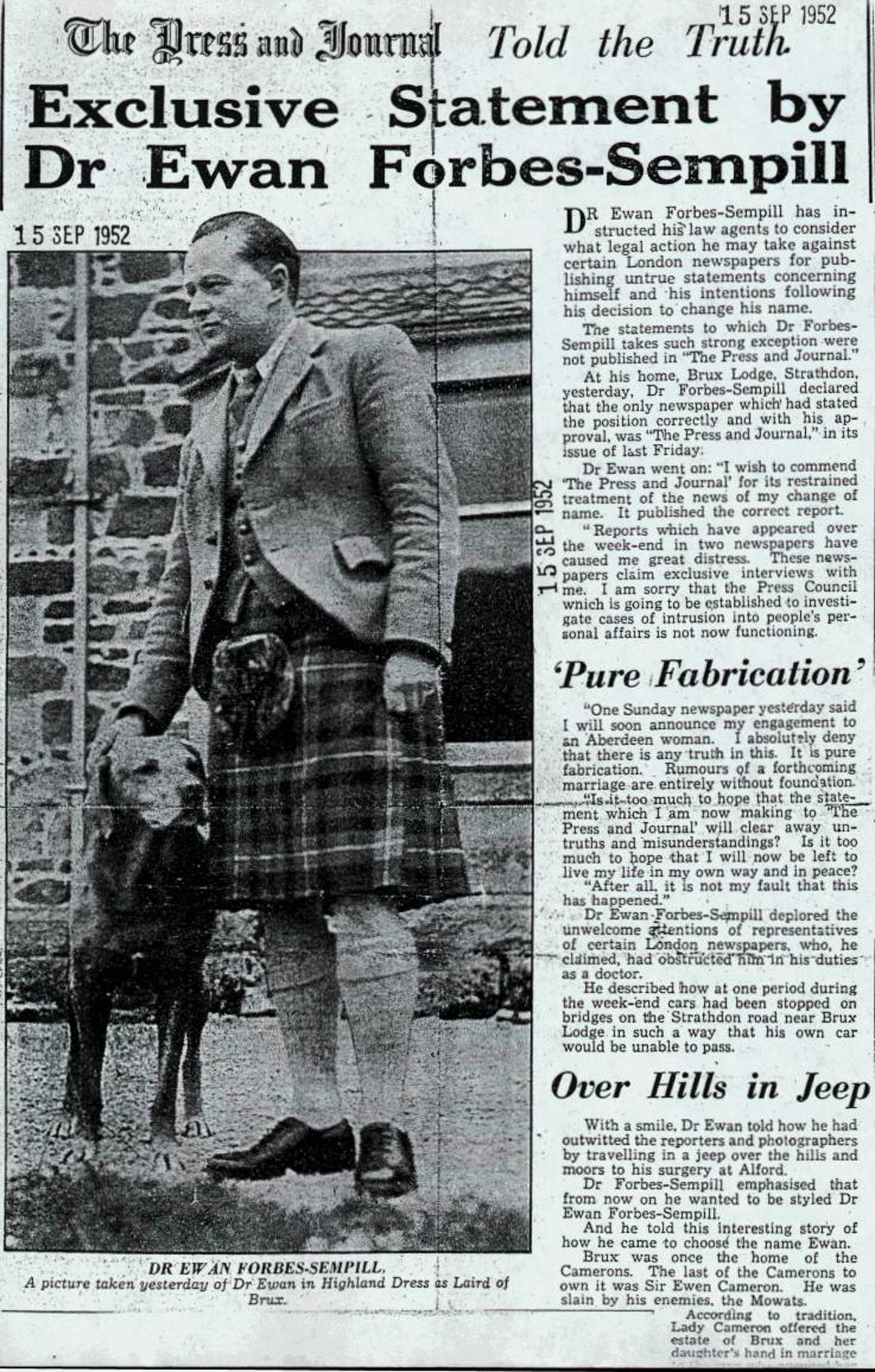

And it all started with a brief announcement in the Press and Journal, less than a month before the wedding, which stated simply: “Dr E Forbes-Sempill henceforth wishes to be known as Dr Ewan Forbes-Sempill”.

A fairly trivial matter, you might imagine. And the majority of readers would have been unaware of the circumstances which had led somebody born into the landed gentry 40 years earlier to change their name and attract the attention of the British press.

But there again, this was a story with everything: romance, secrecy, a judicial drama, a family feud and a little north-east community coming together to protect one of their residents from being hounded by Fleet Street.

Besides, the interest in the person at the centre of these events was heightened by the fact that the “Dr E Forbes-Sempill” in question was Elizabeth Forbes-Sempill: a birth registration which Ewan subsequently described as “a ghastly mistake” and which cast a cloud over the early years of his life in Aberdeenshire.

Nothing was commonplace in this saga, least of all the family ties which linked him to the aristocracy. Ewan’s father, John, who had the titles 18th Lord Sempill and Baronet of Craigievar, was a landowner and soldier who had commanded the 8th Battalion of The Black Watch during the First World War and was wounded at the Battle of Loos.

In the 1880s, he met Gwendolyn Prodger in Germany and they were married in a blaze of publicity in 1892. The couple had four children: William, who became an engineer and an aviator; Gwendolyn, who died of appendicitis before Ewan’s birth; Margaret, a decorated member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force in the Second World War, and Elizabeth, who argued from the earliest days “she” was, in fact, a “he”.

Elizabeth, who was known as Betty by her family, argued vehemently for many years against the name and sex which appeared on her birth certificate.

A tomboy, who idolised her eldest brother and dressed in trousers and a bomber jacket, Forbes refused to attend a girls’ school, was educated at home and, when presented to the Queen as a “debutante” in 1930, was sprouting chin and chest hair, the effects of a heavy course of testosterone.

This was the opposite of a conventional lifestyle in the north of Scotland. But Forbes was an accomplished public reciter who, in the summer of 1930, won the Scots Verse recital contest at the Aberdeen Music Festival, and was paid by Beltona to make a series of recordings of Doric poet Charles Murray.

A life in medicine

When Lord Sempill died in 1934, both the barony and the baronetcy passed to William, who inherited an estate at Brux Castle of about 1,300 acres and took to the lifestyle of a laird with gusto, adopting a broad Doric accent.

But Forbes had no intention of being constrained within a patrician family. Having studied in Germany, the youngster was accepted as a medical student at Aberdeen University and began a new role as junior casualty officer at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

That quickly led to the offer of a GP’s role in Alford in 1945, where the newly-qualified doctor was also called upon to act as a medical officer for a large number of German prisoners of war who were still being held captive in the area.

Forbes was adaptable and inventive, blessed with the attitude that there was no such thing as problems, only obstacles to be negotiated by whatever means necessary.

The Alford area was one of the largest medical practices in Great Britain with some of the worst weather, but in the winter months, the resourceful GP often travelled through 10-foot snowdrifts in a converted Bren Gun carrier vehicle.

Forbes made no secret of the fact he considered himself a man and formally requested a warrant for birth re-registration from the Sheriff of Aberdeen, registering himself as male, and changing his name. This prompted his notice in the P&J and the news did not shock anybody. His plans had been known in advance to many of his patients, who were supportive of his actions and he was a popular figure in the community.

But though he and Isabella were blissfully happy, the story was far from finished.

In 1965, Ewan’s elder brother died, leaving daughters but no sons, and this created a headache in terms of who should be granted the titles and estate.

The barony could be inherited by male or female heirs, and so went directly to Sempill’s daughter, Ann, but the baronetcy – along with the bulk of the land – had to pass to the first male heir. But who was that? The Times cited Debrett’s in reporting that the heir to the baronetcy was the Hon Ewan Forbes-Sempill, “formerly registered as Elizabeth”.

However, this view was challenged by his cousin, John Forbes-Sempill, who argued that the 1952 re-registration was invalid and insisted that Forbes should still be legally considered a woman.

It might have been splitting heirs, but the challenge was taken to the Court of Session, where the case was heard in astonishing secrecy – no papers were publicly filed, and the judge sat in a solicitor’s office rather than in open court.

Indeed, the records were only eventually made available through the National Archives of Scotland in 1991, with additional documents released in 1994.

These showed that no fewer than 12 medical experts were called to give evidence and the rancour between the parties increased as the proceedings dragged on interminably.

It went all the way to Government

The judiciary finally decided that Ewan was a physical hermaphrodite, which would accord with the legal requirement of being “indeterminate at birth”. And yet, the evidence was anything but conclusive. Professor Martin Roth observed in evidence that he felt Forbes’ condition was closer to that of a transsexual, while Professor John Strong described the findings of the medical tests involved as “not wholly conclusive”.

The judge ruled in Ewan’s favour, but that was contested and appealed to the Lord Advocate, who referred the matter to the Home Secretary (and future Prime Minister) James Callaghan who finally decreed in December 1968 that Forbes was the rightful holder of the title, confirming the court’s decision.

But it had been an acrimonious business, one which had taken three years to resolve, and which had sparked considerable family tensions.

His sister, Margaret, wrote a letter in support of John’s claim to the baronetcy, testifying that Ewan had been a girl, albeit one who “went through the phase (as I did myself and so many girls do) of wanting to be a boy.”

With the inheritance case settled, Ewan and Isabella did their utmost to keep out of the public eye and he returned to life as a rural landowner.

Ewan was an elder of the kirk at Kildrummy and was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Aberdeenshire in 1969, who, in his 70s, published a book of reminiscences of his early years called the The Aul’ Days, which obscured the details of his life as “Elizabeth”.

Understandably, in the circumstances, the couple craved their privacy and were unwilling to talk about anything to do with how they had met, let alone the protracted business in the courts. But in 1984 they made an exception for the Evening Express and the paper’s then journalist – and now regular columnist – Moreen Simpson was granted exclusive access to the couple as she delved gently into their existence.

Moreen wrote: “Sir Ewan and Lady Forbes became the subject of rumour, speculation and downright lies in a tightknit little community where he was a respected local GP as well as a member of the landed gentry.

“Everything happened in the early 1950s, yet it is still too painful and too private for them to talk about. However, they can look back at some of the traumatic events with stoical humour and laugh at their treatment at the hands of the gossip-mongers.

“Not unexpectedly, the Fleet Street press corps descended on the village in full force (after the wedding). But Sir Ewan’s first concerns were always for his new wife.

“While some people were shocked by the situation, the locals themselves rallied round the couple. Once, when Sir Ewan was being chased along a country road, roadmen working nearby moved their lorry so it straddled the carriageway, blocked the newshounds, and refused to budge until the doctor was a safe distance away.

“Lady Forbes is reluctant to get involved in any discussion of these harrowing days, although she can smile at the recollection of some of her treatment from ‘the west Aberdeenshire snobs’.

“She once overheard a woman saying that Sir Ewan’s wife was ‘not one of our kind’. Her immediate retort was: ‘No, I’m not and thank God for it!”

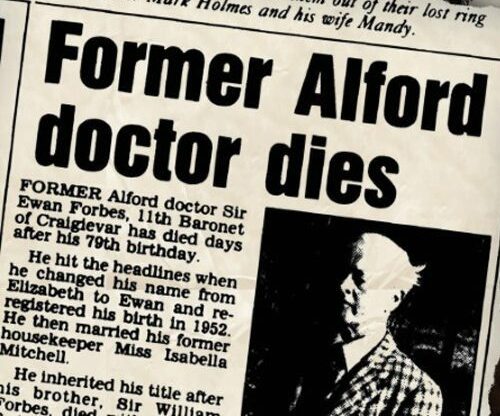

It’s difficult to imagine the response of Sir Ewan – who died in 1991, aged 79 – to learning his story is being turned into a TV drama more than 30 years later.

But, despite his misgivings over the vendetta that broke out between some members of his family, he was convinced he took the right course of action to correct what he perceived as the wrongs which happened after his birth.

‘We were both very happy’

He told Moreen: “I have been very lucky in many ways that I have had so many interesting things to do. I found myself a wonderful and perfect wife and I am glad that I had to work for a living and had the chance to help people as a GP in Alford.

“It would not have been nearly so interesting any other way.”

When Sir Ewan died in 1991, leaving no children, he was succeeded in the baronetcy by his cousin John. Isabella, for her part, passed away in 2002, but always insisted the near-40 years she was married to him was the happiest time of her life.

Let’s hope that is reflected in the TV series, which will be set in and around Craigievar Castle, the seat of the clan Forbes for 350 years.

It’s a compelling enough narrative without any embroidery.

This article was amended on 29/11/22 to remove reference to William Forbes-Sempill, the 19th Lord Sempill, as “a spy for the Japanese”. This statement was based on widespread media reporting at the time of the contents of classified papers released several years ago. His family has asked us to make clear that a recent academic review of the available information concludes that while he did provide Japanese contacts with information, accepted that, technically, he breached the Official Secrets Act on one such occasion, was investigated over many years by MI5, and was removed from the Admiralty by Churchill during the Second World War because his position there was “incompatible with his political activities and his Japanese contacts”, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that he was engaged in espionage, that he revealed anything of major significance or could justifiably be described as a traitor. We are happy to provide that clarification, to link here to those findings and apologise for any upset or confusion.

Conversation