In the autumn of 1962, people across the world crossed their fingers, hugged their families and fervently hoped the pictures they watched on their black-and-white TV screens of a mounting crisis between the United States and the Soviet Union could be resolved without two tribes going to war.

There was shuttle diplomacy, secret talks, the involvement of the United Nations and angry exchanges between the Pentagon and the Kremlin.

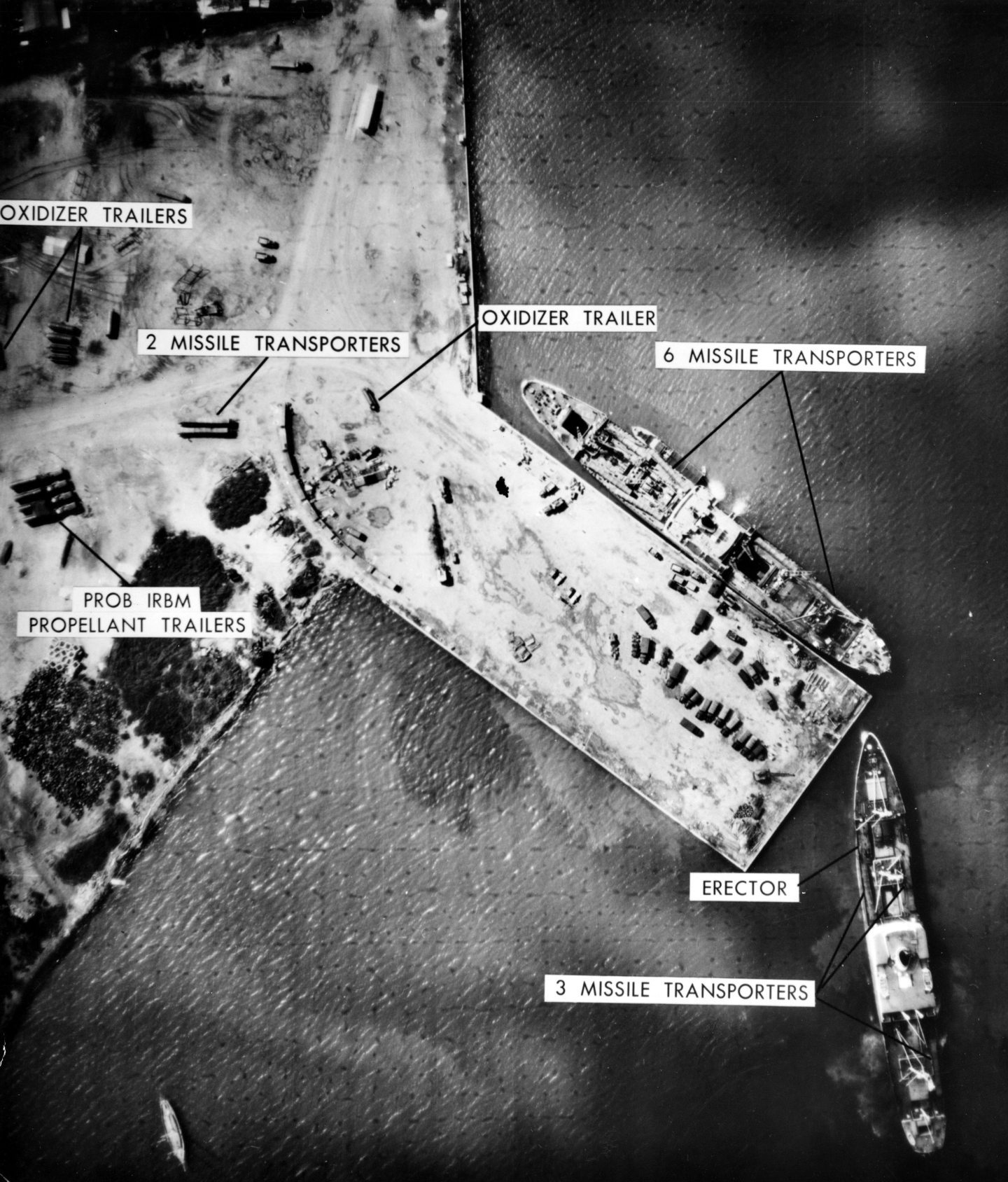

The global superpowers vied for supremacy, backed by vast nuclear arsenals. And the prospect of Armageddon increased after the Soviets installed ballistic missiles at several sites in Cuba, fewer than 100 miles from Florida, and planned to send more.

It was a battle of wills

The island, which had allied itself with the USSR following Fidel Castro’s rise to power, argued it had only accepted the weapons to deter further American attacks, following the Bay of Pigs invasion by anti-communist, US-backed forces the previous year.

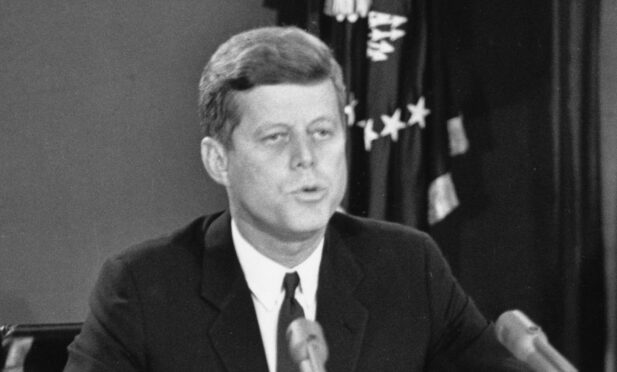

But it led to a situation where two leaders – John F Kennedy in Washington and Nikita Krushschev in Moscow – effectively tried to stare out the other in a battle of wills without appearing weak to their supporters in the West and Eastern blocs.

Hawkish elements in both camps threatened an escalation of hostilities, despite efforts behind the scenes to find an acceptable diplomatic compromise. Who would blink first?

Renowned Scottish historian Jim Hunter has never forgotten how close the world flirted with annihilation during that period.

One morning in October 1962, when the apocalypse seemed a credible scenario amid the doom-laden headlines, the youngster was up as usual at around 6.30am to have a quick breakfast, cycle to Duror Station and catch the early-morning train to Oban – where he was a second-year student in the town’s high school.

The news was full of speculation about whether nuclear weapons might be deployed by the Cold War combatants if discussions broke down between Kennedy and Krushschev.

This was at a stage when the world stood on the precipice – and Mr Hunter, who is now the emeritus professor of history at the University of Highlands and Islands, was among those who sat in class and worried about their future.

My pals and I talked about our fears

He said: “There was no TV reception of any kind in Duror. But breakfast coincided with the seven o’clock news bulletin on BBC Radio’s Home Service.

“A Soviet Russian convoy, it appeared, was steaming towards Cuba where, if its ships challenged the American naval blockade, which President Kennedy had put in place around the island, would be treated by the US as an act of war – a war, it seemed likely, that could escalate into a nuclear exchange.

“While on our way to Oban, at breaktime and at lunchtime, my pals and I must have talked about what might be about to happen.

“What I remember with a clarity that has not faded is attending a music class held on the top floor of what was then the newest part of the Oban High School complex.

“Music was not my strongest subject. That helps to account for the minute or two or three or four when, having lost all sense of what our teacher was saying, I gazed through the classroom window at the hills to the south-east.

“In that direction was Glasgow and, a little closer, the American submarine base on the Holy Loch. Both, I knew, were bound to be Soviet targets if a nuclear war broke out.

Was this the end of the world?

“Would it be possible, I wondered, to see from where I sat, the resulting mushroom clouds that would spell my own, my family’s and everyone else’s annihilation – if not from the blast, then from the radiation which would follow a nuclear strike.”

In the intervening years, it has emerged the incident revolved around more than the impasse in Cuba. Kennedy was aware his defence staff had far more missiles than the Soviets, while Krushschev believed the installation of weapons so close to US territory would balance the threat posed by America’s own missiles based in Turkey.

But such considerations were hardly mentioned amid the sabre-rattling and, for millions of people, the next few days were filled with anxiety. As so often, diplomats devised an exit strategy – whereby the Soviets removed the Cuban missiles while the Americans did likewise in Turkey – but the world had edged to the brink.

Fife-born nurse Jane Taylor, who has family in Aberdeen, was pregnant at the time and, working as a nurse, was caught up in the sense of panic as the crisis deepened.

She said: “What I remember most is the constant terror every day of wondering if it will be our last. We were advised to be ready to whitewash our windows to protect us from the blast, fill all our receptacles with fresh water, take to the hills if we could – the government at the time was full of wacky ideas which only served to panic people more.

Some opened up old war shelters

“The police were told they had to be prepared to evacuate people to the countryside and, as nurses, we were expected to wheel our patients on beds, chairs and trolleys in a likewise direction. But I was concerned about my unborn child and my husband, David.

“It was a terrifying time for us all. Some people even brought their wartime shelters into use again – stacking tins of food in them along with pots, kettles, anything that would hold water, bedding, candles, matches – you name it, people stored it.”

Eventually, as world leaders realised how catastrophic any descent into war would be for their people, commonsense prevailed. They stepped back from the brink, albeit with coded communiques which hinted they had claimed at least a moral victory.

Prof Hunter added: “In large part, I think war was averted in 1962 because the Russian leaders of that time, for all the threat they may have posed, were men who had seen, in the wake of Nazi Germany’s 1941 invasion of their country, the horrors that war – even non-nuclear war – inevitably brings.

“These men were not given to taking risks. But their successor in the Kremlin (Vladimir Putin) isn’t like that. This is our misfortune – the misfortune, in particular, of Ukraine.”

Former Aberdeen councillor and local historian John Corall has plenty of emotive memories of different crises which happened during the Cold War and was a teenager as the stakes intensified during the US naval blockade of Cuba.

The water could not be wasted

He said: “I remember the time of the 1956 Hungarian uprising, the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and the Czechoslovakian invasion of 1968 by the Soviets.

“We knew there was a four-minute warning and that water was very precious and could not be wasted, because you could live without food, but not without water.”

“The establishment fear was widespread civil unrest. But, as children, we just accepted there could be war at any time and the testing of the air raid sirens reinforced that feeling. We did think that some of us would be blown to smithereens.”

Conversation