There was nothing flamboyant or headline-grabbing about the way in which the British Broadcasting Corporation came into existence 100 years ago.

Instead, on October 18 1922, a consortium was formed, licensed by the GPO, which comprised a number of large firms who provided the initial capital of £100,00o, backed by other radio manufacturers who were willing to pay £1 for an “ordinary share”.

It was decreed that the cost of funding the newly-born BBC would be met from a 10-shilling licence fee which the GPO levied on all owners of “domestic receivers”, which, in these days were the radio sets which were gradually attracting a bigger audience.

Reith dismissed TV as a passing fad

The corporation’s development was overseen by the company’s first Director-General, Sir John Reith, an imposing fellow born in a home nicknamed “Beefy Castle” in Stonehaven, who resolved that its mission should be to educate, inform and entertain.

From the outset, this strict religious figure had no time for tittle-tattle, frivolities or highlighting controversy and scandal on his news bulletins. Indeed, when interviewing potential employees, he would commence the interrogation by asking them: “Do you accept the fundamental teachings of Jesus Christ?”

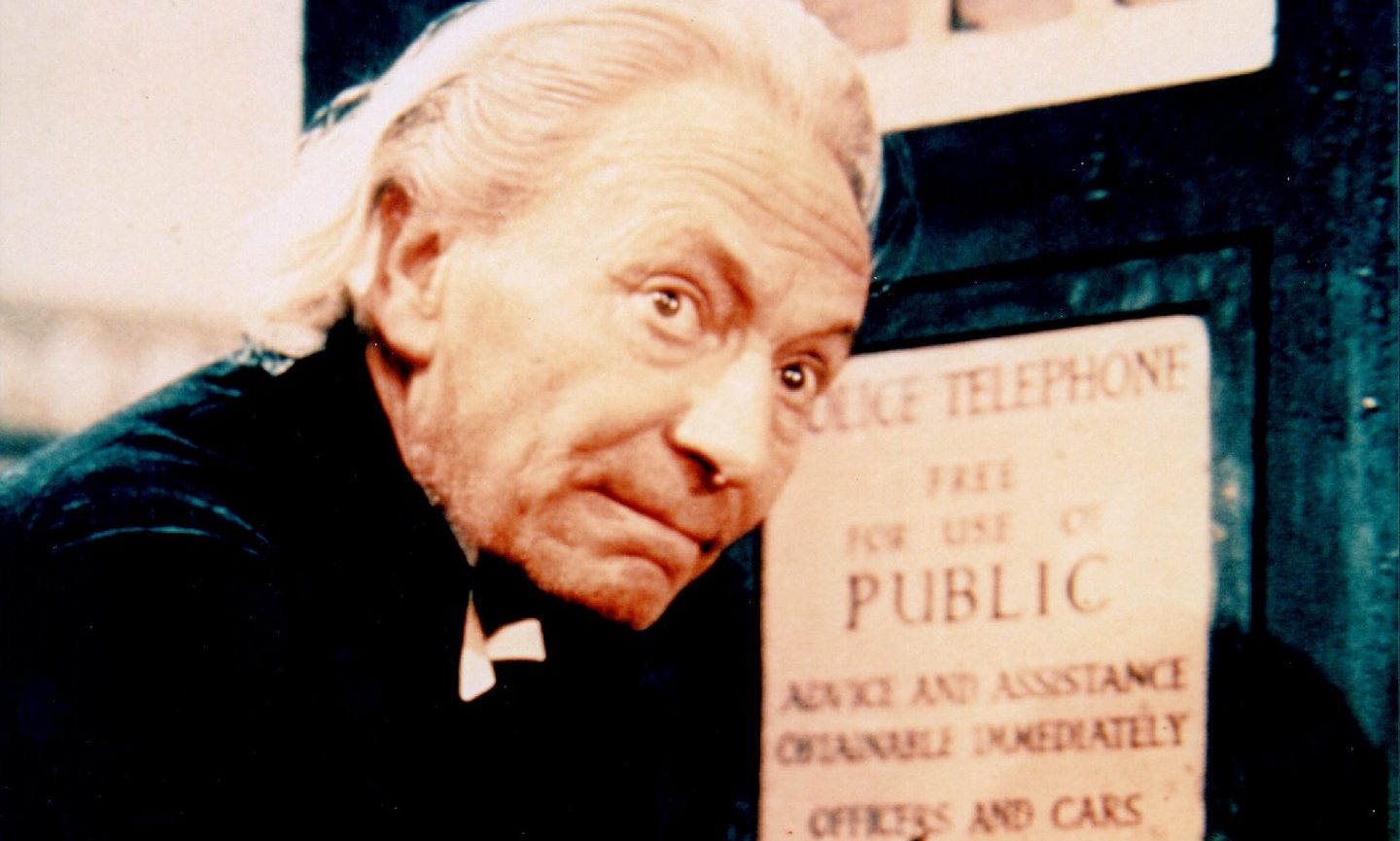

As somebody who lamented the rise of television – and initially dismissed it as a passing fad – one wonders what Reith would have made of the BBC’s history through the days of Doctor Who and Top of the Pops to the Two Ronnies and Morecambe and Wise and the creation of reality TV formats such as Strictly and The Great British Bake-Off.

Yet, while it still commands massive audiences for such events as The Olympics, the World Cup, Wimbledon and Eurovision, and during its recent coverage of the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the vast network is facing increasing pressure from streaming services, social media companies and politicians who believe that the licence fee – £159 for colour TV, and £53.50 for black and white – should be scrapped.

Just last weekend, questions were asked about the way the BBC in Scotland responded to First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s remark that she “detested the Tories”, while, a few days later, the Business Secretary at Westminster, Jacob Rees-Mogg, accused it of sparking panic among the financial sector and breaching its impartiality guidelines.

It’s hardly surprising that even those who broadly support the BBC admit its future looks uncertain. Former correspondent, Eleanor Bradford, said: “Radio Scotland constantly surprises me in its ability to do big occasions better than Radio 4 (such as the recent coverage of the death of The Queen at Balmoral) and you only need to travel abroad to realise that the BBC is one of the most respected news services in the world.

“But we have to remember how much change the BBC has had to deal with in a short period. For decades, all it had to worry about was whether to have one channel or two, and which white, male Oxbridge graduate would read the news next week.

“When I applied for a BBC job in the 1990s, I had to drop my regional accent to even get an interview and wouldn’t dream of putting my holiday job in a supermarket on my CV. By the time I left in 2016, applicants were trying to outdo each other’s working-class credentials and a part-time supermarket job was seen as positively as a degree.

‘The BBC is on a shoogly peg’

“Within a few years, the BBC has had to adapt to on-demand viewing, streaming giants, social media, online news, as well as being forced to reflect a more diverse world, devolved nations, and try to figure out how to provide true balance (which is more nuanced than just giving equal airtime to both sides).

“Sadly, I have to face the fact that the future of the BBC is – to borrow the perfect Scottish phrase – on a shoogly peg. The audience is frustrated when the BBC doesn’t reflect a complex society in the way we want it to and this frustration is compounded by the fact that we have to pay for the BBC whether we like it or not.”

The licence fee issue is currently under discussion, with some people calling for the corporation to consider subscription models as well as reducing its online coverage of news, sport, politics and entertainment at a time when the public is effectively paying for their journalists to cover the same territory as national and regional newspapers.

Politically, there are many people in every party who are critical of the BBC’s efforts to be non-partisan, whether in covering Brexit, Scottish independence, the economic downturn or the internecine warfare in Downing Street. Yet the SNP MSP Gillian Martin is among those who believe not all the condemnation is justified.

Ms Martin, who taught TV production and media studies for 15 years, said: “The BBC news output in the last two decades has faced criticism, with so many on all sides determined to assert it is biased against them, and I think this is largely unfair on the journalists working in newsrooms all over the country – some of whom I know.

“But I do think public confidence started to be shaken in the Blair years when the former, and very well regarded Director-General Greg Dyke, was effectively removed for standing by his journalists on their reporting of the Iraq war.

“Ever since then, I think there has been too much political interference in the higher echelons, and their somewhat ham-fisted attempt to prove they are ‘impartial’ has led to some of their brightest stars leaving to flex their more critical journalistic muscles elsewhere – which is a real shame.

“That said, I have always been, and continue to be supportive of, the licence fee model. You only have to go to the USA to see what happens when you don’t have that.”

The reality is that the BBC has been embroiled in political rows since the General Strike in 1926 when Reith locked horns with Winston Churchill over refusing to toe the Government line and the two men became implacable enemies.

But, according to Sandy Bremner, who worked for the BBC from 1990 until retiring in 2018 as its managing editor for the North East and Northern Isles, the debate should concentrate more on how the network moves forward rather than constant kneejerk reactions from its opponents.

He said: “In nearly three decades at the BBC, I came to see political attacks as a given. They came from nearly every level of Government, in Scotland and the UK. Sometimes they were direct threats. It’s what happens whenever original journalism reveals awkward truths. It goes with any good reporting.

“We sometimes fail to appreciate that independent journalism has to be defended by every journalist, sometimes in the face of significant threats. The battle for an impartial BBC was fought by Lord Reith, against Winston Churchill who wanted to use it as a mouthpiece of Government. It has been fought by every succeeding generation.

“They key is distinguishing between justifiable criticism requiring redress, and naked intimidation. As long as the BBC earns the public’s trust by refusing to buckle under that kind of pressure, it will be hard for any politician to destroy or diminish it. Of course, that won’t stop some politicians from trying, as we’ve seen in recent months.

“But then there’s the question of how to engage younger generations who regard the licence fee as a historical relic. The future of BBC funding is again a battleground.

‘It is still a great British invention’

“It has been grasped by some vested interests as a golden opportunity to harm the institution. So the current challenge to the public is a simple one. If you do value the BBC, now is the time to defend it.”

Nobody has ever argued the BBC is perfect, but it is now in the firing line, north and south of the border and with enemies to the right and left. It will have to devise a new funding model, but there’s no indication of that happening. So what’s in store?

Eleanor Bradford said: “Overall, despite its many infuriating tendencies, the BBC is still one of the greatest British inventions of all time. I think the danger is that we will only realise what we have lost when we have destroyed it.”

Conversation