Families sat huddled around candles and coal fires in the dark. Electric lifts in high-rise blocks had no power. A man woke up to discover the water in which he kept his false teeth had become a block of ice during the night.

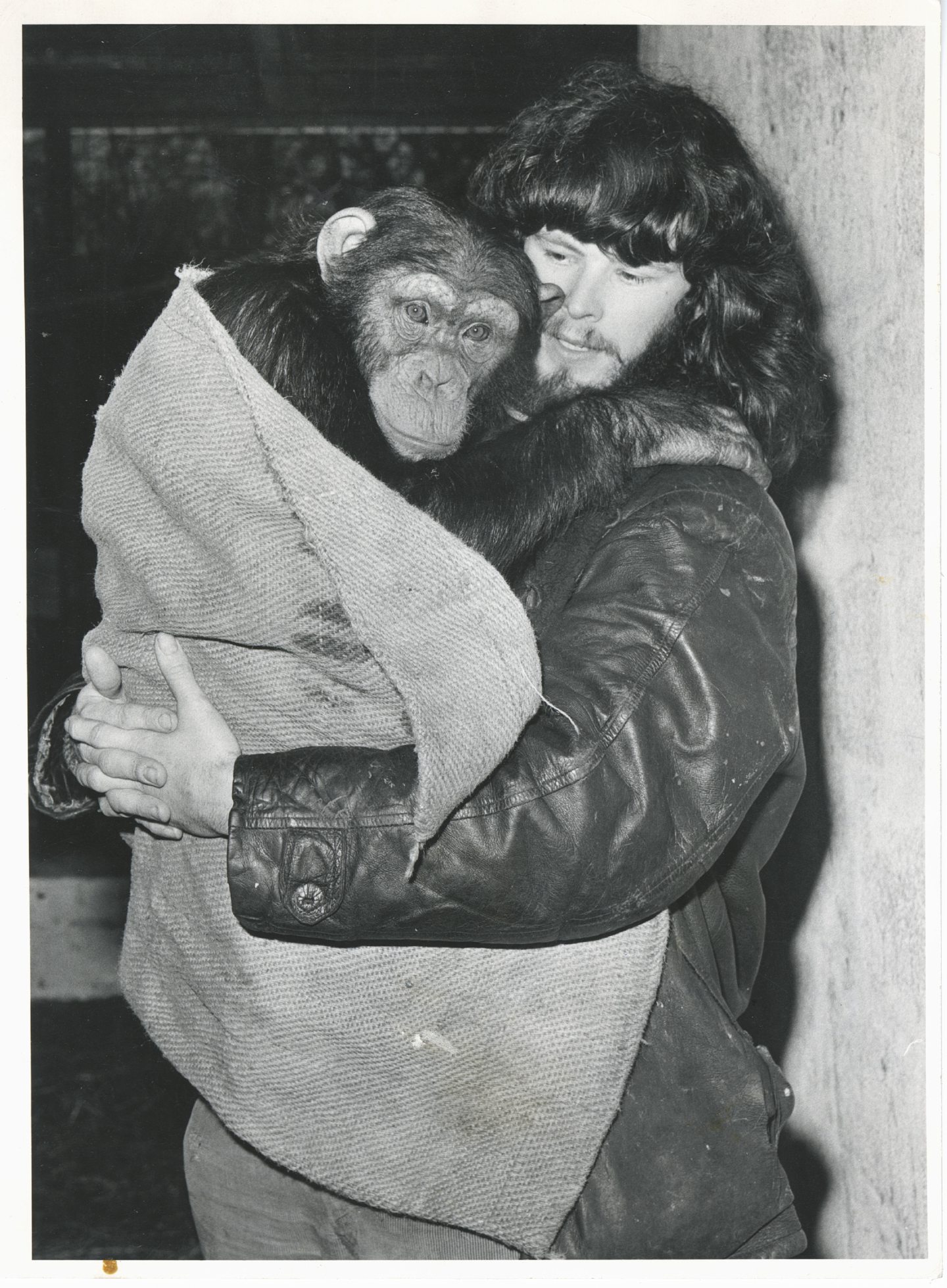

At Aberdeen Zoo, in Hazlehead, one of the chimpanzees, Heather, had to be wrapped in blankets because she was frozen. Meanwhile, at a city theatre, a drama group carried torches as they attempted to stage their latest production of Hello Dolly.

This was part of daily life across the north of Scotland in the winters of 1972 and 1973 when power cuts, strikes and the introduction of a three-day week meant the lights could go out at any time. Schools often closed, pubs regularly shut and many sporting fixtures had to be staged in the afternoon because floodlights weren’t available.

It’s nearly half a century ago, but the prospect of a new wave of power outages this winter was highlighted last week by John Pettigrew, the chief executive of the National Grid, who said the company would have to impose rolling power cuts on “those deepest darkest evenings in January and February” if generators failed to secure enough gas from the continent to meet demand, particularly if the country suffers a cold snap.

The parties clashed over the economy

It also emerged that the BBC has prepared scripts which could be read on air if energy shortages are the catalyst for blackouts or the loss of gas supplies. These would attempt to reassure the public if a “major loss of power” causes mobile phone networks, internet access, banking systems or traffic lights to fail across Scotland, England and Wales.

Much of this will seem familiar to those who lived through the 1970s when trade unions and the Government frequently clashed over wage demands and the Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath insisted he couldn’t bow down to their demands, sparking myriad arguments with his Labour opponent, Harold Wilson.

But, although the power cuts caused problems for many people, and the lack of supplies on the shelves eventually led to food rationing, the majority of Scots struggled through the crises and some younger people even regarded the disturbances as a big adventure.

Aberdeen’s former Lord Provost, Barney Crockett, can recall the anxieties which were felt by the public as they prepared for temperatures to plummet and sought comfort from such items as candles, camping stoves, Thermos flasks and paraffin heaters.

He told me: “It will be hard for many to understand what high inflation and energy shortages mean in practice. You have to look back to the 1970s when the double whammy of rocketing oil prices and a miners’ strike led to regular power cuts and the introduction of a three-day week.

“Power was strictly rationed and commercial businesses were only allowed to operate on three consecutive days per week. Feelings ran high as to who was to blame, but, at the same time, there was a strong community spirit which helped us through.

“Everyone was buying paraffin heaters, candles and torches and sharing them whenever they were in short supply. Power cuts were staggered between areas, so people would visit relations or friends in another part of the city to avoid the worst.

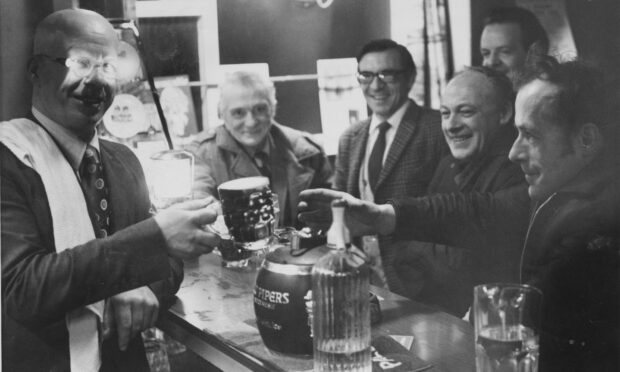

“Pubs had limited hours and some were closed [and there was ban on streetlighting], but they were very busy and cheerful when nearby areas were in darkness.

Life was no picnic for those in flats

“A particular problem in Aberdeen was that many residents lived in high rise blocks which had often only been recently completed. They not only had all-electric heating, but electrically-powered lifts and water pumps.

“So, not only was there no heat or light, but there was no water… and the prospect of taking your messages up 10 flights of stairs. Again, people had very strong reliance on friends and neighbours. A great emphasis was put on prioritising the National Health Service and that made many feel positive. We may discover in the challenging months to come whether people will respond in the same way they did then.”

Author and BBC football presenter Richard Gordon has never forgotten his mother lighting candles around their council flat in Lamond Place in the Granite City and the family “sitting in the dark trying to amuse ourselves”. But they were adaptable to the difficulties, as were his colleagues in the region.

He added: “I remember Aberdeen having to play Celtic in a League Cup tie at Pittodrie,

which was in November 1973. I cannot recall if the school – Skene Square Primary – was closed or if I was allowed off that day. But I was certainly at the game, a 0-0 draw, which kicked off early on Wednesday afternoon because floodlights couldn’t be used.”

Journalist Jim Strachan said: “My in-laws had a nice old house with a coal fire, so when power cuts hit our all-electric apartment, we buzzed off to them for a heat and hot food.

“Also, I remember that a power cut occurred during one particularly cold night. When my uncle went to bed, he put his dentures in a glass of water. Well, when he woke up the next morning, it had frozen solid.”

There was a gallows humour as Scots lived up to their reputation as God’s Frozen People, yet the blackouts, frost-encrusted homes and empty shelves were usually tolerated by families, whose senior members had faced worse during the Second World War and the austerity years of rationing books which followed the conflict.

So can we expect similar stoicism if the light and heating goes off in the new year? Historian and former UHI professor Jim Hunter is among those with doubts.

He said: “We were living in a rented flat and one of our lingering memories concerns the complexities of having three or four friends round for a meal.

“We would study the power cut schedule which was published daily and work out who among us was best placed to do the cooking by virtue of having early-evening power.

Attitudes have changed since then

“We recall getting a casserole cooked and then, when the lights were about to go out, loading it into a carrier bag and heading off to one of our friends’ places where the lights were about to come on, have our meal and head home to find our own lights about to come on again. And all this by bus.

“There must have been plenty of older folk for whom things were a whole lot tougher. But then, they had been through the war, had seen its horrors at first hand and had lived for years with rationing. A few power cuts must have looked pretty piddling.”

It remains to be seen whether Scots will show the same stuff upper lip when they find themselves in the dark as winter rages outside.

Conversation