I was recently sitting in a dirty, smelly, hot bus station near Alicante in Spain.

I was fed up and having a moan about my ride to the airport, then airport shuttle bus, then hanging around for this next bus, then lastly a walk to my final destination. What a hassle, I thought to myself.

Suddenly, something, or someone, caught my eye. A guy in his twenties, blind and with white stick, carefully manoeuvring himself through the bus station.

“You don’t know you’re living George,” a voice in my head said as I watched this guy. I felt embarrassed at myself, and at the same time much respect for the blind guy who just got on with it.

The following day I did a little test. I put my bandana round my eyes and decided to try and do everyday things, “blind”.

I walked into a chair, stubbed my toe on the kitchen door, dropped a couple of things, couldn’t find other things, and made one heck of a mess when attempting to make a cup of coffee.

I never realised how focused you have to be when pouring boiling water into a cup, when you can’t see.

I gave up after 20 minutes, sat down and felt like a failure.

How do blind people manage it? And that was only in the comfort of my own home. I didn’t even dare step outside into the garden.

As for being out in the big bad world, like my guy in the bus station, I can’t even comprehend it. It scares me. It feels impossible.

Walking down the road, popping into the shops, getting on a plane, a train, a bus… we all take it for granted. Imagine doing all that, in total darkness, blind.

What is it like to be blind?

Well, if you are reading this, you’ll never know. How could any of us know? It’s impossible.

I’d guess that the vast majority of blind people live full lives, albeit with daily challenges the likes of you and me will never know. Let’s take a look at some of them.

Surely, the biggest challenge has to be navigation. And not just out in the big bad scary world where there are obstacles such has roads, pavements, kerbs, cars and such like, but also inside the sanctuary of their own homes.

The golden rule here seems to be that if you live with a blind person or even visit with them, you must not move any object in the house, without first asking them of course.

This is vital. Think about it, if the blind person knows that the kettle sits touching the back kitchen wall and the spout points horizontal to said wall, if you turn that kettle to a different angle, they could burn themselves from the steam next time they make a cuppa.

How many times do we move a chair in our house without even thinking? Every day I’d guess, even just a foot or two. Again, very dangerous for a blind person, who needs to know that everything is always exactly in the same place.

As for out and about, again I think of my blind guy at the bus station. At least he knows where everything is inside his house, but outside with all its potential dangers? It’s mind-boggling really just how brave people must be to step outside into the darkness.

I’d imagine that’s where the invaluable work of guide dogs comes in. Nothing impresses me more than when I see a guide dog at work. The way it navigates its way through the streets, past other people, lampposts, then sits down at the kerb and waits until it’s safe to lead its human across the busy road. Remarkable.

Have you ever stopped in the street and helped a blind person? I have, years ago. I don’t now. Allow me to explain.

This man was in no distress, and was standing calmly at a junction. I took his arm and helped him cross the road. He said thanks and that was it. However, I’ve since learned that I shouldn’t have done that, I shouldn’t have presumed he needed help, I should have asked him first. Chances are he has crossed this street more times than I have and knew exactly what he was doing.

From what I’ve been told by those who know way more than I do on this topic: “Unless it’s an emergency situation or you can see trouble ahead, always ask, don’t presume.”

There are numerous famous blind people, from writers to mathematicians, to scientists, lecturers and lawyers. Three that instantly come to my mind are the politician David Blunkett, singer Andrea Bocelli and pianist Nobuyuki Tsujii.

I recently watched an old clip online of David Blunkett as Home Secretary. Standing at the dispatch box, he was on fine form. He rose to high office, and never let his blindness hold him back.

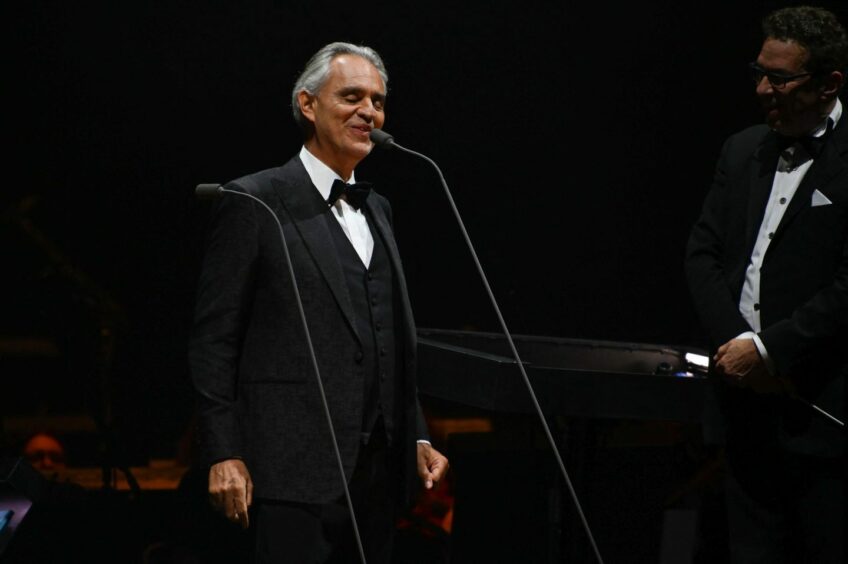

I adore the voice of singer Andrea Bocelli. I also admire the fact that he doesn’t wear dark glasses, and when he finishes a song and hears the applause, his face lights up and he beams the biggest smile ever.

The following day, I tried again. More determined this time. Bandana back on over my eyes, I sat down and cleared my mind.

“Focus George,” I said to myself. I also stopped trying to “look” for things. It was actually easier than the day previous.

I sat down with my coffee, burned my lips slightly on drinking, but nonetheless, I felt I’d made a decent go of it.

However, when going to the toilet, I realised I needed to sit down to pee as opposed to standing up and missing. That had never occurred to me before.

Feeling rather proud of myself, it suddenly dawned on me, although I had managed much better second time round, it was because I was seeing with my mind’s eye. I knew where certain things were, I know what a kettle feels like, I know where the kitchen sink is, I know what a fridge is and that there are shelves in it.

But what if… what if I had been blind from birth?

I’ve often pondered the following question. What is worse? Turning blind at some point in your life, or being blind from birth?

As devastating as turning blind must be, for me, the worst surely has to be being blind from birth.

I cannot fathom, I simply cannot, never having seen. Forget about cliches like a sunrise or a flower, but imagine never having seen everyday items like a chair, a desk, a spoon, a door, a dog. I cannot get my head round that at all.

I’d love to hear from any reader who has a blind family member or a friend. I’d be fascinated to hear from them and learn more. Be it them having become blind at some point, or having been blind from birth.

Our eyes, our ability to see, so vital in so many ways, yet just another of the many things we all take for granted.

Nobuyuki Tsujii is a Japanese pianist and composer. I urge you to watch the four-minute clip of him playing piano at Carnegie Hall. You’ll easily find it on YouTube.

Watch right to the end as he takes his applause and observe his humility. Nobuyuki was once asked how he stays in time when performing with an orchestra as he can’t see the conductor. He replied: “By listening to the conductor’s breath.”

I am in total awe of this young man, who has been blind since birth, therefore has never even seen a piano…

Conversation