It was a Eureka moment for Jonathan Comerford when he walked into the Peacock printmaking studio in Aberdeen four decades ago.

As somebody who had grown up in apartheid South Africa and witnessed the endemic racial discrimination which existed between whites and non-white people, here is a man who has tackled prejudice at the grassroots and inspired his compatriots through art.

But there was a litany of obstacles and so many in the cultural community who preferred to keep their heads down, ignore the injustice in their homeland, and pretend it wasn’t really happening, even as their country was branded an international pariah.

Jonathan was conscripted on a compulsory basis by the South African army to take part in a border conflict, with which he vehemently disagreed. For 15 months, he served in the forces and it was a desperate situation for the youngster.

But then, suddenly, the Cape crusader had the chance to travel to Aberdeen to meet with friends who were working in the energy sector. And it, literally, changed his life.

‘The place was a wonderland for me’

The experience left its mark on him and he spoke with something approaching reverence about the world of new possibilities which opened like Aladdin’s cave.

He said: “Having arrived in Britain with very little, I decided to visit friends living outside Aberdeen who were associated with the offshore oil industry.

“On journeying to the city one Saturday, I enquired about any printmaking facilities from an artist, who was then the artist in residence, at the Aberdeen National Gallery.

“He mentioned the Peacock studio in Castlegate and, thereafter, I went to find the studio.

“On walking in, I felt as if I had arrived in a very special place and environment. An environment which was first and foremost open access without the need to have had a formal training in printmaking to become a member.

“I had arrived in a place I could never have dreamed of. It was phenomenal and it was like a wonderland to me. And I’ve never forgotten the thrill I felt that day.”

South Africa had nothing like it

There was nothing remotely comparable in Cape Town or anywhere else in South Africa; a country where it was written into the legal system that whites would be granted access to opportunities which were denied their black and “coloured” counterparts, whether in science or business, sport or politics or culture.

The sort of inclusivity which Jonathan discovered at the Peacock venue was not merely absent back home, but it would have been deemed illegal if the authorities had learned about it.

So he had to be inventive as he developed his skills, both as as an artist and printer and as a political campaigner.

He recalled: “This type of [open] environment simply did not exist at the time in South Africa during the apartheid era.

“And, access to [print] presses to further one’s professional skills and practice as a professional artist did not exist other than if you were a student at either a university or a technical college.

Everything geared towards whites

“Access to knowledge or to equipment was used as a tool of power governed by an elitist system of privileged white academia and gallery owners.

“As a working-class, first-generation caucasian African, I was marginalised alongside the rabid mass denial of access of numerous educational and public facilities to the oppressed black African community [who formed the majority of the population].

“So, it was a very special experience, one which ended up becoming one of the fundamental policies besides the freedom of association, speech and creativity of the workshop which I eventually established, Hard Ground Printmakers, in Cape Town.”

How to avoid any more army life

Jonathan was in his element in the Granite City, but cold reality beckoned. He needed to head home and was staring at the prospect of a return to military service.

It was the last thing he wanted, but this resourceful character had been inspired by his time in Scotland. And that proved the catalyst for a momentous decision.

As he said: “A loophole existed. Essentially, I was state property. But I discovered that if I became a sole proprietor of a company, the government can’t get use of you again.”

It sparked his decision to bring the Peacock concept to South Africa, allowing him to follow his vocation as an artist, avoid the draft, and create a meaningful way of breaking down barriers and joining forces with kindred spirits from all races and backgrounds.

The hard ground was his concept

After scraping up enough money to buy a plane ticket, he returned to Cape Town with a slideshow about Peacock. Using it as a blueprint, he attracted a host of investors, one of them an art-loving diamond diver.

And eventually, in 1989, Hard Ground Printmakers was born and a quiet, but effective, revolution had been set in motion.

He said: “My condition to the investors was that there would be no repayment, but I would be responsible for producing artwork by South African artists in Cape Town.

“With the money, I rented a space and built the presses with enough cash left over to last the year. I then embarked on an incredible arts journey, pulling in and helping develop a host of art talents, particularly from deprived black communities.

“With no affiliation or funding with institutional bodies, the studio operated as an entirely independent, autonomous entity. This was key to giving voice to artists against the apartheid regime.

“I already knew quite a lot of black artists and comrades who were fellow students; and people would come to the studio because I had access to the artists and the artists had access to Hard Ground. There was so much solidarity and support.”

It changed many lives for the better

Jonathan encouraged myriad artists to learn a variety of printmaking techniques that could help them translate their works into highly finished products. The studio subsequently became sustainable through sales of art.

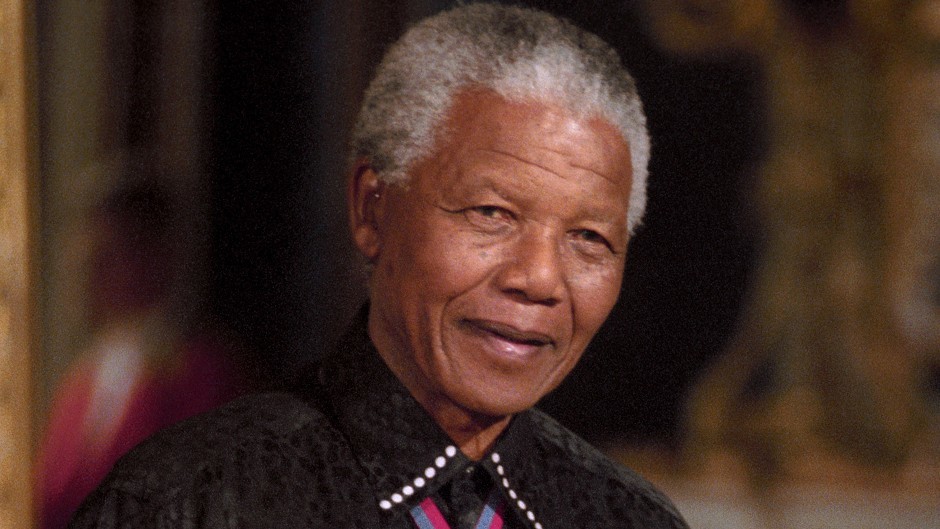

It was the talk of the [Cape] Town and, as the 1990s advanced, South Africa was transformed by a peaceful revolution and the election of Nelson Mandela as a president who was prepared to preach unity and look forward rather than waste time in raking over the decades where he and his race had been treated as second-class citizens.

It was a seismic period and Jonathan was thrilled at how matters unfolded, although, 30 years later, he isn’t so naive as to imagine all the old scars have vanished.

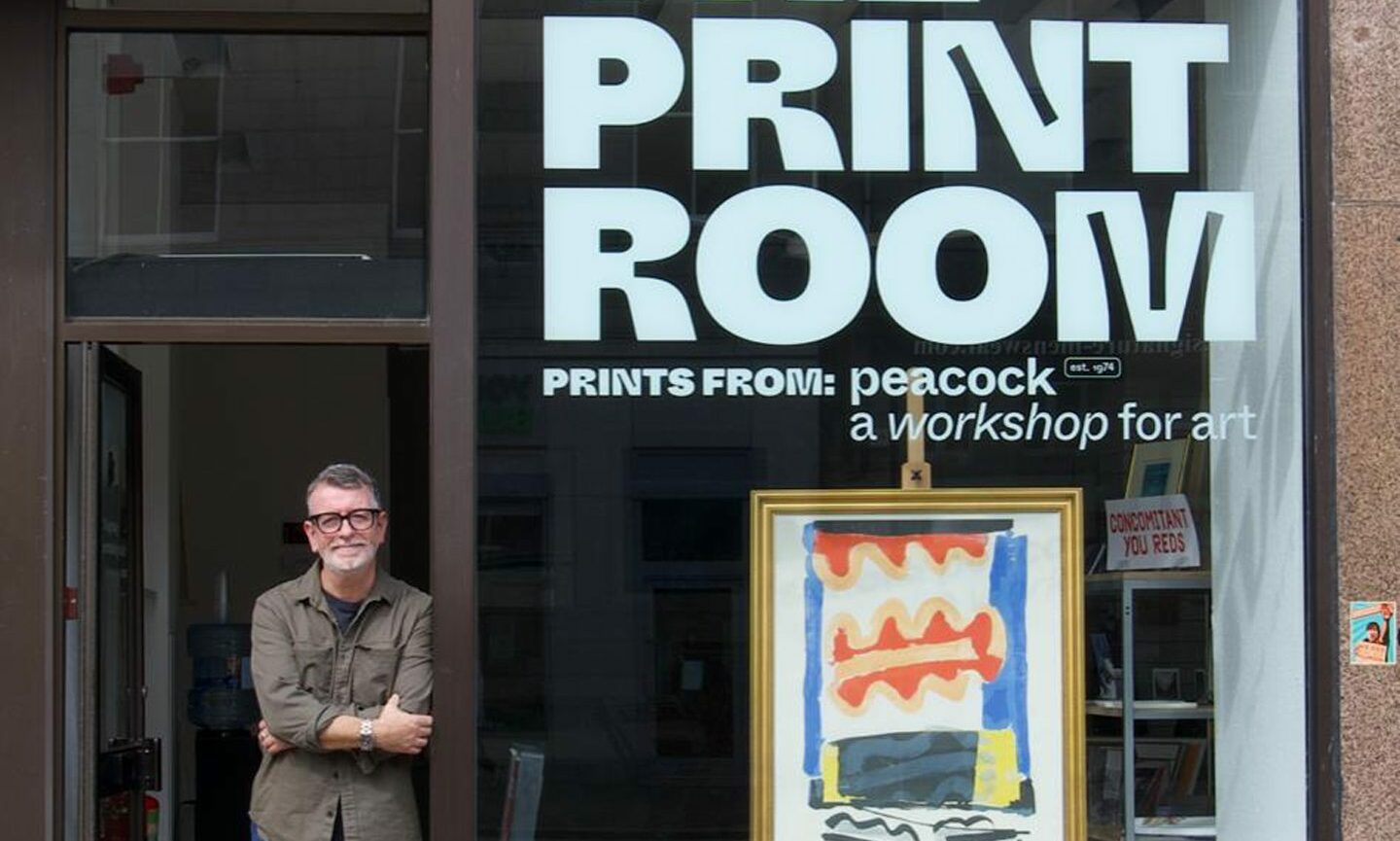

But, at least, as he is proving in a new exhition, Printmaking Sans Frontiers 1989-2021, which is on show in Aberdeen until November 23, that small steps can lead to major breakthroughs if one has the requisite ideas, innovation and instincts to succeed.

And he’s not finished there. His next ambition is to establish a printmaking trade route between Cape Town and Aberdeen – something else to bring folk closer together.

We’re better when we work together

He said: “The opposition I got – and still get – largely came from the privileged white art community and institutions.

“It impacted to such an extent that, during the 15 years I ran my studio, not a single university or technical college-employed printmaking lecturer visited it to meet the artists and discuss ways forward in establishing a more open educational system.

“The white-privileged gallery owners also did not engage or visit the studio to see what current printmaking was done or could be sold in their galleries.

“The fact I was able to run Hard Ground Printmakers for the length I did was due to the solidarity of all the artists and organisations, who worked with me or used the studio.

“The story and the prints produced by the artists illustrates the assistance in breaking down the apartheid barriers, of which there are still many to fall.

“Aluta continua” [the struggle continues].

The exhibition Hard Ground Printmakers 1989-2021 runs at The Print Room, 252 Union Street, Aberdeen, until November 23. Jonathan Comerford will give a free talk at the venue tomorrow and Sunday at 1pm.

Five questions for Jonathan Comerford

- What book are you reading? “The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass.”

- Who’s your hero/heroine? “Chris Hani [the leader of the South African Communist Party, who was assassinated in 1993]”.

- Do you speak a foreign language? “Kaapse Afrikaans”.

- Favourite band/music? “Bob Marley and the Wailers/Babylon by Bus”.

- What’s your most treasured possession? “My life”.

Conversation