There was never another night like it in the Granite City.

And Aberdeen was left in a state of shock and mourning as an unprecedented level of death and destruction was inflicted on soldiers and civilians.

It wreaked a terrible price for all those who lost loved ones and had their homes blown to pieces. And even now, 80 years later, the pictures of the Aberdeen Blitz testify to the devastation which was caused by the Luftwaffe as bombs rained down on April 21 1943.

By this stage of the Second World War, the tide was slowly turning against Adolf Hitler’s forces, but the terrible events of that attack on the north-east offered a stark reminder that maintaining the victory push came at a heavy cost.

In less than an hour, myriad housing blocks were reduced to rubble, service personnel at the Gordon Highlander barracks found themselves in a vision from hell, and thousands of men, women and children were forced to seek safety in the numerous shelters created to protect the public in a community that was nicknamed “Siren City”.

The enemy aircraft killed more than 120 soldiers and civilians as explosions proliferated throughout the night during the worst incident of the conflict for people in the north-east.

In the space of just 44 minutes, 127 bombs fell, wreaking havoc on or destroying more than 12,000 homes, killing 98 civilians and 27 soldiers, and wiping out a family of four, including two young children and a baby.

It had started out as a calm April evening and nobody could have predicted how the peace would be shattered in such an apocalyptic manner.

But suddenly there was the ominous sound of a rhythmic drone as a group of 10 Luftwaffe Dornier bombers approached their target from the coast.

Swooping as low as 100ft over Aberdeen, they flocked to the north-east like deadly birds of prey and were followed by another 15 shortly afterwards.

It was as well organised as you might have expected from an air force which had already laid waste to many countries across Europe and the planes flew in diminishing circles, dropping bombs with seemingly indiscriminate regard.

While the harbour and shipyard had been heavily attacked in previous air attacks after the outbreak of hostilities, the object of this foray was to terrorise the citizens and inflict maximum civilian casualties.

People’s homes crumbled in minutes

Hilton was one of the first Aberdeen regions to bear the brunt of the onslaught, with a direct strike to Middlefield School, where a young teacher, Sybil Spicer, was trapped by a falling beam – and her leg subsequently had to be amputated. (Although this brave woman was undaunted and eventually became headmistress of Cornhill School).

As the conflagration escalated, around 19 bombs tore through the estate and surrounding area, killing whole families in Cattofield Gardens and Bedford Road after their homes crumbled on top of them as smoke and screams filled the air.

The front of Causewayend Church on Powis Place was reduced to rubble and a large headstone from St Peter’s Cemetery on The Spital crashed into the bedroom of a neighbouring property after it was propelled through the air by a stick bomb.

St Mary’s Church in Carden Place received a direct hit from an explosive, which crashed through the roof and finally detonated in the Crypt Chapel. Practically every window was blown out by the blast and the two side walls were cracked from top to bottom.

Yet, it was a measure of the resilience of the Aberdeen public, in the midst of the chaos, that the patched-up church held Communion just three days later with a full choir and large congregation.

They couldn’t ignore what happened and mourned those who were lost. But the feeling among these people was defiance. Nazism had to be beaten. And it WAS beaten.

John Alexander, one of the young residents in Powis Place, told the Evening Express in 2008: “It all happened so quickly. One moment, everything was normal. Then people were being killed all around us. There was no warning at all. I’ll never forget it.”

Carnage came indiscriminately. On the Kittybrewster railway, a missile landed close to a shelter where 13 men were taking refuge and four of the group were killed.

Papers couldn’t report Blitz

The northern part of George Street was set alight and nearly every plate-glass window was blown out. A nearby school – which later became the site for Aberdeen Technical College – was targeted, next to a night nursery where about a dozen children and three nurses mercifully escaped with cuts.

Around Hutcheon Street, Broadford Works was severely damaged and the Kilgour and Watson hosiery factory was destroyed by fire.

A phosphorus bomb fell through the roof of the Northern Co-operative Society’s grocery store at Berryden as the offensive continued to cause extensive damage.

The Evening Express front page on Monday April 26 was actually about the bombing of Aberdeen, but due to regulations introduced by the authorities to preserve morale, the newspaper was unable to mention the city by name in its coverage.

Instead, it said: “Digging operations continue among the ruins of wrecked homes to recover bodies of the victims of last Wednesday’s air raid on a north-east town.

“It is now known that some families have been wiped out. But difficulty is being experienced in establishing the identity of some of the bodies recovered.

“Some of the ARP personnel had their homes destroyed in their absence on duty. One man and his wife were at a report centre when a message was received that their own home had been struck by a bomb.”

Yet, if that censorship obscured the lethal consequences of the attack, nobody on the ground had any doubt about the severity of what had transpired.

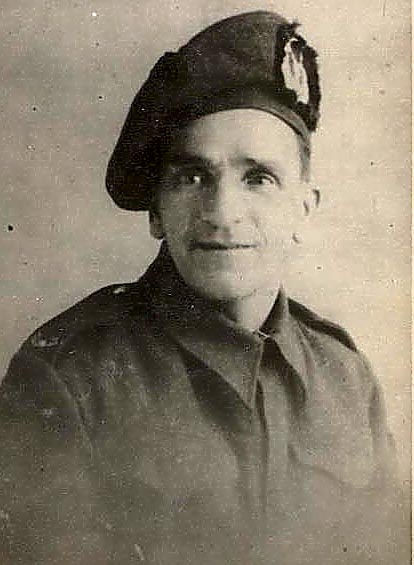

Walter Wren was among those who was serving with the Gordon Highlanders in Aberdeen when he was caught up in the Germans’ mass bombing raid.

Walter’s story was all too typical

Lance Corporal Wren, born in Gateshead in 1904, was one of the 27 soldiers who perished during these desperate hours. His great-granddaughter Heather Williquette spoke to the Press and Journal and revealed more about her predecessor’s tragic story.

She said: “Walter and my grandfather Joseph both served in the war and, although Joseph came home afterwards, Walter remained in Aberdeen.

“According to his death certificate, he was found the next morning (on April 22) in Charlotte Street School, aged 39.

“The list of the soldiers who fell records that he was in the 30th Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders, but it has been difficult finding out much information.”

The terse notification of his death was typical of that dreadful time in history. It comprised one sheet of paper, with the formal acknowledgment that he had been “killed by enemy action”. This was followed by the message: “I am to express the sympathy and regret of the Army Council at the death of the soldier in his Country’s service.”

The letter, which was dispatched to his mother at 51 Taylor Terrace in Gateshead, was one of tens of thousands issued between 1939 and 1945.

The raid had particularly grim consequences for those in the Bedford Road area, which was obliterated in a few minutes. And it was the catalyst for one of the worst civilian outrages in the Granite City when the Cox family, comprising mother Williamina, aged 22, and her three children, Freda, three, Frederick, 17 months and John, five months, were all killed at their home at 60 Bedford Place.

Their fate was only confirmed the following morning when search parties and officials discovered that many houses had been reduced to a grievous pile of rubble and ash, with no sign of those who had once lived there.

It was a heavy toll to bear

Other families were rocked over a longer period. Private Richard Wilson was one of the first PoWs to return home to Claremont Street from the Far East in October 1945. But, as the Aberdeen Journal reported, his sense of relief was soon mingled with sorrow.

The paper said: “Not until he arrived back in the city did he learn that, during his captivity, his brother, David, had died a prisoner in the Middle East; his sister, Georgina, had perished as a result of an accident while serving with the ATS in North Africa; and another sister, Mrs Lowson, had died at her home.

“Within a fortnight of Mrs Lowson’s death, the parents, Mr and Mrs William Wilson, lost their home at 425 George Street, in the Aberdeen Blitz.

“Understandably, the family reunion was tinged with sadness.”

Despite the devastation, there were tales of heroism, stoicism and miraculous escapes.

One Bedford Road resident, Albert Adams, told the Evening Express how he dashed through machine gun fire with his two young children to reach safety.

He said: “The bullets were flying furiously. I crawled into the ash house on my way to the shelter for protection, but when I looked up, there was no roof.

“It was no place for us, and we made a dash to the shelter and safety.”

It was only once the dust has settled that the scale of the death toll became obvious. And, as you might expect, Aberdeen was a very sombre place in the weeks ahead.

There is one particularly poignant photograph that shows the cortege of army vehicles taking some of the blitz victims from Bedford Road and Cattofield down Seaforth Road to the Trinity Cemetery on May 2 1943.

As they slowly advanced, their heads bowed, hundreds of Aberdonians lined the streets in silent tribute to the 98 civilian fatalities, many of whom were killed in their own homes. And many said a prayer that they had been spared. Because there really was a completely random element to whether people lived or died.

Consider the case of one resident on Stafford Street – who was unharmed in the first wave of attacks – but after returning to his tenement flat to collect his prized Great War medals, a second incendiary device struck the building and he was never seen again.

It was a lottery as to who lived

As Peter Nicol told the Press and Journal in 1993: “My daughter, aged six, was seriously ill in the Aberdeen Hospital for Sick Children. We had been asked to be near at hand, to be on call, so we were living with friends in Cattofield.

“However, Cattofield not only had a rain of bombs, but the street was raked by a hail of bullets. The windows were blown in and the lights went out, but our hosts’ small son – who was around seven or eight – had his arm around my wife’s shoulder and was saying: ‘It’s going to be all right, don’t worry’.

“When it was over, I ran out to get to the hospital as quickly as possible. What a scene of devastation hit my eyes – the house next door had simply disappeared.”

Conversation