There is no such thing as a typical day in Professor Lorna Dawson’s life.

She could be knee deep in a soil pit at a crime scene, examining a shoe in the laboratory, exploring and evaluating trace evidence data, plotting maps of search areas for investigators to prioritise, attending conferences, chatting to students, writing reports and statements, lecturing on Zoom and Teams, or presenting evidence in court.

Yes, and sometimes that all happens in a single day for Prof Dawson, the head of forensic soil science at the James Hutton Institute, whose expertise in unearthing crucial evidence has been pivotal in a string of high-profile cases, from the “World’s End” murders and the conviction of Angus Sinclair to the soil samples taken from tools in a garden shed which helped snare Swindon double-murderer Christopher Halliwell.

Lorna’s become a fictional character

She has also given evidence in the inquiry into the death in police custody of Sheku Bayoh, assisted in the search for missing Fraserburgh man Shaun Ritchie and examined soil from the vehicle of William MacDowell, who was convicted of murdering Renee MacRae and her three-year-old son, Andrew, during a high-profile trial last year.

Meanwhile, the little girl who grew up reading Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fabled Baker Street detective, who was one of the earliest pioneers of soil analysis, has had her work depicted in Ian Rankin’s Rebus novel In a House of Lies, and liaised with Ann Cleeves on the books and TV series, Shetland and Vera.

Yet, as she told me, she never wanted fame for fame’s sake, but a life which mattered, which made a difference and had a positive impact on others. And she has succeeded.

‘I have always loved and studied soil’

Globally recognised as an expert in her field – or fields – this indefatigable woman has the attitude that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

And, just like Holmes, her specialist subject is the minutiae, the faint imprint or microscopic smudge, which could make all the difference between a killer being caught or escaping punishment.

It all started back in the 1960s when she was growing up in the Scottish countryside and formed a deep attachment to the land which piqued her imagination and curiosity.

She said: “I have always loved and studied soil.

“Having been brought up in rural Angus, where I walked the tattie fields with my dad, watching the seasons change through the growing potato crop and how the yield depended upon the soil conditions, I soon realised the importance of caring for our soil.

‘Follow your dreams’

“The wildflowers I searched for depended on a soil appropriate for their survival. Then I went on to study the geography of soil, the chemistry and physics of soil, and then its application as a tool in searches and as trace evidence in the investigation of crime.

“Soil science is the ultimate inter-disciplinary subject – there has never been such a vital time to be a soil scientist – with its central role in creating fresh air, clean water, nurturing a rich biodiversity, nutritious food, a safe platform to build on, an amazing carbon store and a cultural treasure trove.

“For anyone who feels passionate about working in a particular field, I would tell them to follow your dreams, work hard and dedicate your efforts to make a difference.”

Prof Dawson’s involvement with such organisations as the National Crime Agency has demonstrated the technological innovations which have happened in her sphere.

But she insisted there was nothing glamorous about these assignments, let alone the sort of Eureka moments which happen on a regular basis in fictional TV dramas.

Instead, it’s a painstaking process and there is a similarity in her philosophy to that of her compatriot Professor Dame Sue Black, particularly in terms of bringing a combination of intellect, science and empathy to what are often harrowing cases.

Science develops at rapid pace

She said: “I have been extremely privileged to be invited to assist investigators, lawyers, wildlife crime officers and others in their case investigations.

“During the last 20 years, the science has developed so rapidly we can now analyse such tiny amounts of soil that a perpetrator won’t even realise they have trace evidence on them. All case work is about care, clarity and caution, in ensuring that everything is carefully recovered and recorded at the crime scene, analysed methodically, and evaluated without bias and presented in court with clarity and respect.

“It’s vitally important to be able to assist the decision makers, the jury, in coming to the right decision, so that justice is done for the family and friends of the victims of crime.

“It’s not a subject that should ever be glamorised, because it is the lives of individual people and their liberties that can be affected, so while it is important to communicate with the general public, such as at science and literary festivals and working with crime authors, it must always be done with respect and sensitivity.

“However, starting with soil, which is the very surface of our globe, and using that basic material to help investigators solve questions and the courts to bring justice…well, what could be more worthwhile than that?”

‘A true honour’

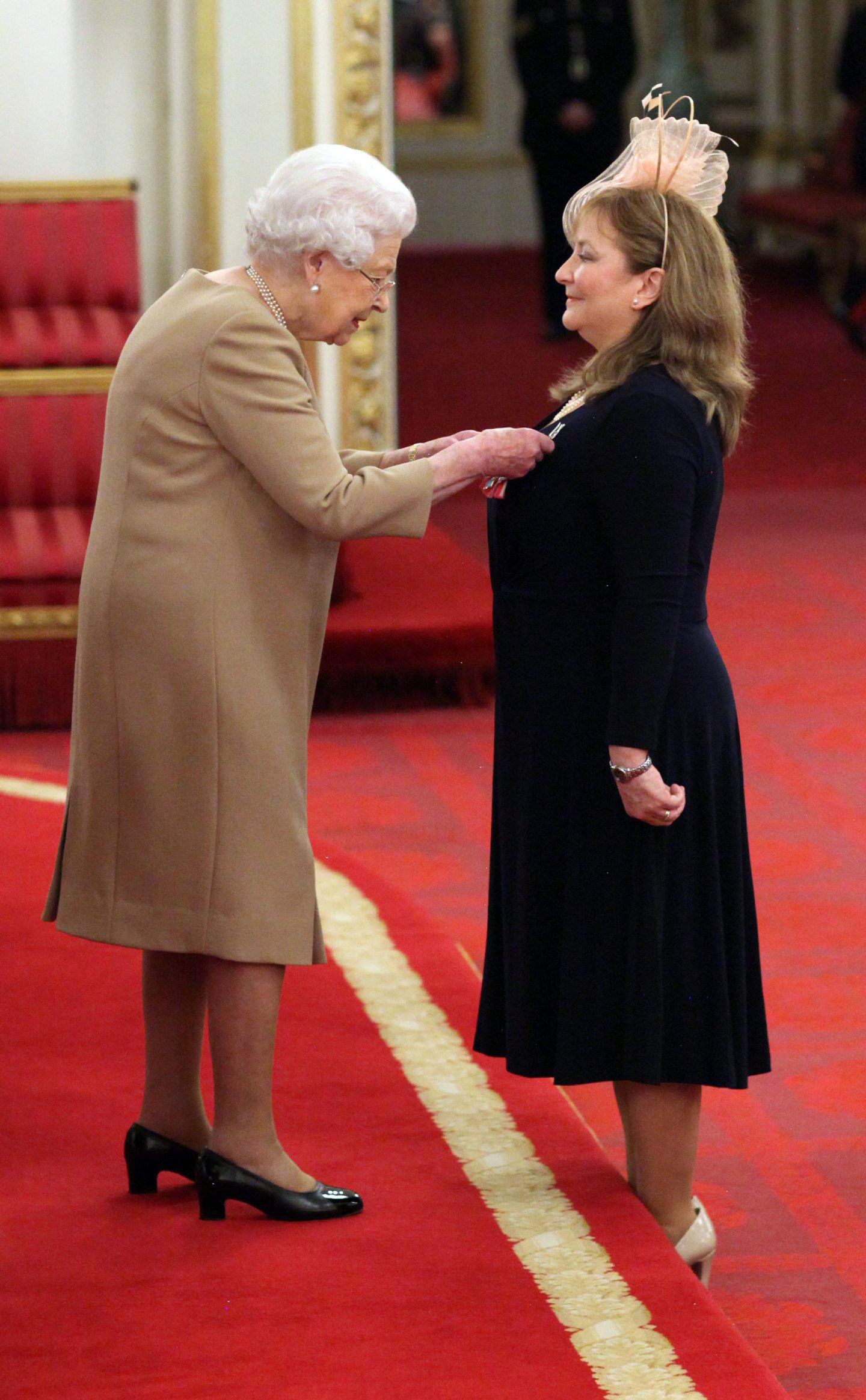

Prof Dawson, who was made a CBE by the Queen at Buckingham Place in 2018, recently became the first recipient of the Royal Society of Edinburgh’s medal for earth and environmental science. But, while she values these plaudits, she wants to stress that everything she has achieved has been as part of a larger team.

She said: “It was a true honour to be awarded the first ever RSE James Hutton medal for excellence in earth and environmental science. It seems particularly poignant in that the institute where I work also bears the great geologist/agriculturalist’s name.

“Also, the fact that the medal recognises communication is science with real impact means so much to me, as I believe it’s so very important to make everyone aware of how science can impact on society, including the geosciences.”

Her life has changed dramatically

It’s a long time since she broke her leg in two places while picking potatoes at the age of 10, but that experience, harrowing as it was, opened her eyes to the marvels of deduction, forensic medicine and the pipe-smoking figure in the deerstalker hat whose sleuthing in The Sign of the Four offered an introduction to a brand new world.

As she recalled: “Sherlock Holmes predicts the actual street where a person had walked by the colour of mud on the man’s shoes.

“He established the principle of tracking where someone had been from soil and demonstrated that you can tell where it has come from by looking at the colour and consistency of that material. It was inspirational.”

Even at that stage, Prof Dawson realised the devil was in the detail. And that’s something she has brought to all her endeavours in scratching beneath the surface.

Five Questions for Lorna Dawson:

- What book are you reading? “An old paperback I picked up in a charity shop. Dead Souls by Ian Rankin. A great Edinburgh thriller narrative.

- Who’s your hero/heroine? “It would have to be Queen Elizabeth II who is the best example ever of loyalty, love and duty to so many, especially as she was thrust unto her role so unexpectedly.

- Do you speak any foreign languages? “French and a little Spanish and Italian – after years of fantastic European collaboration.”

- What’s your favourite music/band? “1970s rock. David Bowie, Rod Stewart, Eric Clapton – I saw them all in concert in the 1970s/80s. Brilliant.”

- What’s your most treasured possession? “My family. Family photos and videos. Memories. Priceless.”