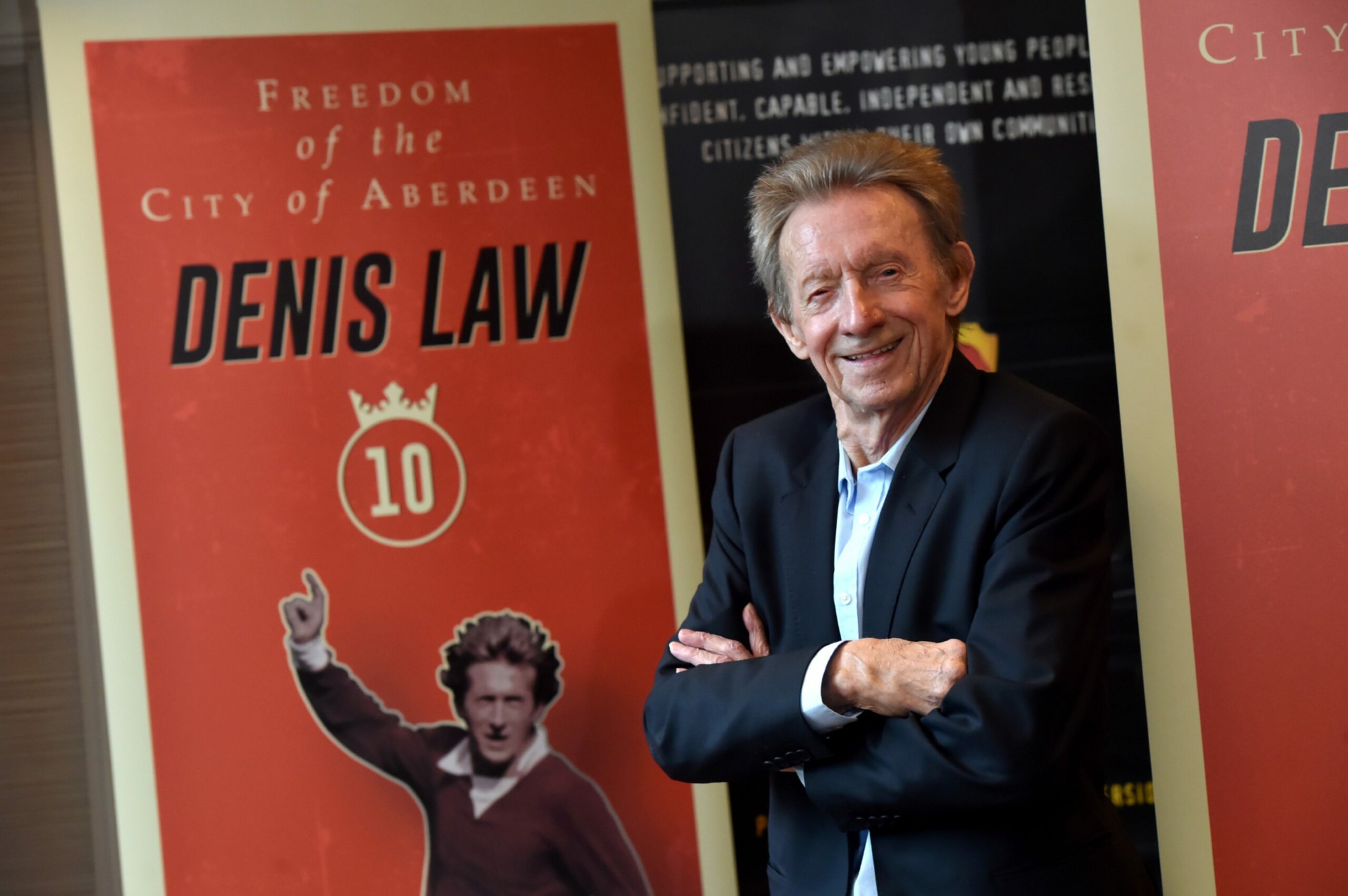

There wasn’t room to swing a cat in the city centre when Denis Law was accorded the Freedom of Aberdeen in 2017, even though you would have fancied this blithe boy to weave past any crowds in his heyday.

He was a bespectacled, skinny skelf as a teenager, somebody who asked himself: “What am I doing?” when he was offered the chance to join Huddersfield as a teenager and suddenly realised he had no idea where it was. And yet, once he had travelled down to England, he blazed a trail that few of his compatriots have come close to emulating.

That’s one of the reasons why the Aberdeen public, young and old, male and female, congregated in such huge numbers to celebrate the fellow who excelled for Scotland and Manchester United and orchestrated magical mayhem wherever he ventured: he was The Lawman and the King of the Stretford End, who visited his roots at regular intervals and helped new generations of youngsters to thrive in the game he loved.

It’s one of the more curious aspects of his career that he was never in contention for a contract at his home club, despite showing plenty of potential as a youngster.

But, in November six years ago, he took centre stage in the place which moulded him – and he told me why Aberdeen held such a special place in his heart.

Early days in Printfield Terrace

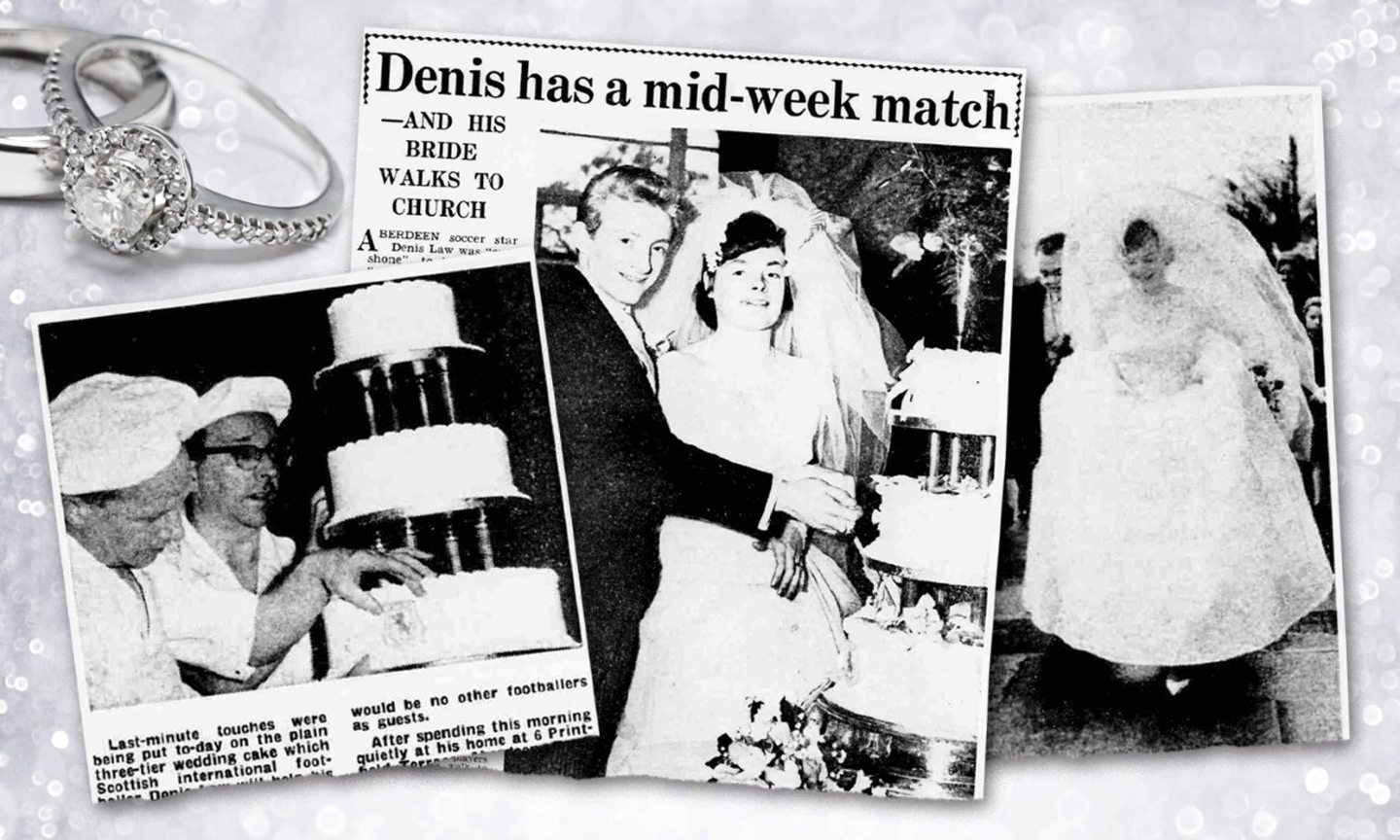

It may have been a long time since he entered the world in February 1940 and grew up at 6 Printfield Terrace in Woodside, but one of the things that makes him special is how much he has been prepared to talk about those early days as a tenement child.

Although he performed at the highest level, become the only Scot to secure the prestigious Ballon d’Or (in 1964), won the hearts of the Old Trafford faithful by scoring twice on his debut and broke the hearts of England’s World Cup-winning team a year later at Wembley, there’s not a trace of the pampered prima donna in his personality.

He has never forgotten the grinding poverty he lived through as a youngster and has spoken openly about his mother having to hand in her husband’s only suit to the pawnbroker’s when he went away to sea on a trawler every Monday.

As he recalled: “I didn’t own my first pair of shoes until I was 14. I could have had free shoes, but they were like big tackety boots and we were too proud to take them, because everybody would know they were handouts.

“Whenever I look back at how we lived when I was a child, it’s probably difficult to explain to the modern generation. Our house had no carpet, no central heating and no television. There was a pantry instead of a fridge and I didn’t eat any food during the week except soup and sago pudding, which looked like frogspawn.

They must be toughest jobs of all

“There was just one bathroom for the entire family and we’d have a bath every Sunday night, because that was the only time there was any hot water.

“We just got on with it because there was nothing else for it: at that time, all mining and fishing families lived in similar, straitened circumstances and, as a result, I’ve always thought they must be the two hardest jobs in the world.

“You had to roll up your sleeves and get on with it. But your pals were your pals, you all stuck together, and we always looked out for each other if somebody was struggling.”

Denis never had ambitions to follow in his father’s footsteps. Football provided an alternative and a merciful escape, but he didn’t have the sea legs, in any case.

He said: “I went out on the trawler with my dad just the once from Aberdeen harbour.

“It was a beautiful sunlit day and the water was calm when I joined him, but even then, the little boat was bobbing up and down the further out we steamed.

They were risking their lives for us

“As I struggled to keep down my breakfast, I remember thinking: ‘Good heavens, this is not for me’. I never really got to know my dad as much as I would have liked.

“But I always had admiration for him and others like him, considering that every day these men went down the pits or out to sea, they were risking their lives and working in often terrible conditions to earn a barely adequate living for their families.”

He didn’t have any vast ambitions in these formative years. He was hardly any threat to Hercules or Adonis: undernourished, under-developed, and weighing in at eight stone with a terrible squint. But then the chance came out of the blue to go for a trial with Huddersfield Town and his fortunes were transformed in a few weeks.

At the height of his powers, Denis genuinely was a wondrous, mischievous sprite. He dazzled for Scotland and scored one of the goals when they famously defeated world champions England 3-2 at Wembley in 1967.

The story beyond the goals

The statistics speak for themselves – he amassed 30 goals in 55 Scotland internationals and 237 goals in 404 appearances at Old Trafford and helped the club win the First Division in 1965 and 1967 – but they never told the full story.

Because, whether in refusing to celebrate his goal which consigned United to relegation after he moved to their great rivals, Manchester City in the 1970s, or in his obvious delight at performing alongside such stellar figures as George Best and Bobby Charlton, there is a decency, dignity and sense of derring-do stamped in his DNA.

Christmas came early for Denis when he was granted the Freedom of Aberdeen at the end of November 2017 and his joyful expression as he journeyed along Union Street was only matched by the excitement of the audience who cheered him to the rafters.

He said later he could hardly believe the news when he was told about the accolade, despite having established a legacy trust, joined an initiative to remove No Ball Game signs from the parks where he spent his formative years and explained how bags of rowies were frequently despatched from the north-east to his home in Manchester.

Aberdeen has always been my home

As he added: “When I was first told, I couldn’t believe it, because it is the sort of thing that happens to other people and I thought the council must have the wrong number.

“The parade down Union Street was wonderful and to come out on the Town House balcony and get such a warm reception is something that will stay with me forever.

“I have always called Aberdeen home and this weekend has meant so much to me.”

Denis was diagnosed with dementia in 2021 and has good days and bad days. But he was full of admiration for Alex Ferguson’s Gothenburg Greats, who triumphed in Europe in 1983, and will themselves receive the Freedom of the City this week.

The feeling was reciprocated by Dons captain Willie Miller, who recently stepped into the role of ambassador at the Denis Law Legacy Trust.

As he told me: “You can’t exaggerate his influence on the game. Pele once said that he was the only British player who would have walked into the great Brazilian side of the 60s and, putting it simply, he is the greatest Scottish footballer who has ever lived.”

That’s why the public turned up in their thousands to applaud Denis Law. Just as they will flock to pay homage to Miller and his Pittodrie colleagues who jousted with giants and made their city proud of their feats forever.