It’s one of those Ripping Yarns which has become established as part of British history; the details of Scottish Commando David Stirling single-handedly recruiting a group of renegades and creating the SAS which became an elite fighting force with the motto Who Dares Wins.

The legend, plucked straight from a Boys Own comic, was encouraged by the Allied top brass during the Second World War.

Influential general Bernard Montgomery was even quoted as saying in 1942: “The boy Stirling is quite mad, quite, quite mad.

“However, in a war, there is often a place for mad people.”

Aberdeen soldier had prominent role

That’s the myth. But now, Tom Petch, a former Troop Commander of 22 SAS, who has become an award-winning film director and producer, has offered a more down-to-earth theory about those involved in the creation of the Special Air Service – and his new book, Speed Aggression Surprise, brings to the surface the prominent role played by an Aberdonian who had to keep so many secrets to himself it became second nature.

It’s a compelling work, packed with such well-known characters as acclaimed authors Evelyn Waugh and Ernest Hemingway and Hollywood film star David Niven. Quite apart from Stirling and his brother, Bill, there was the iconic Irishman Paddy Mayne, who was capped for Ireland and the British Lions at rugby union.

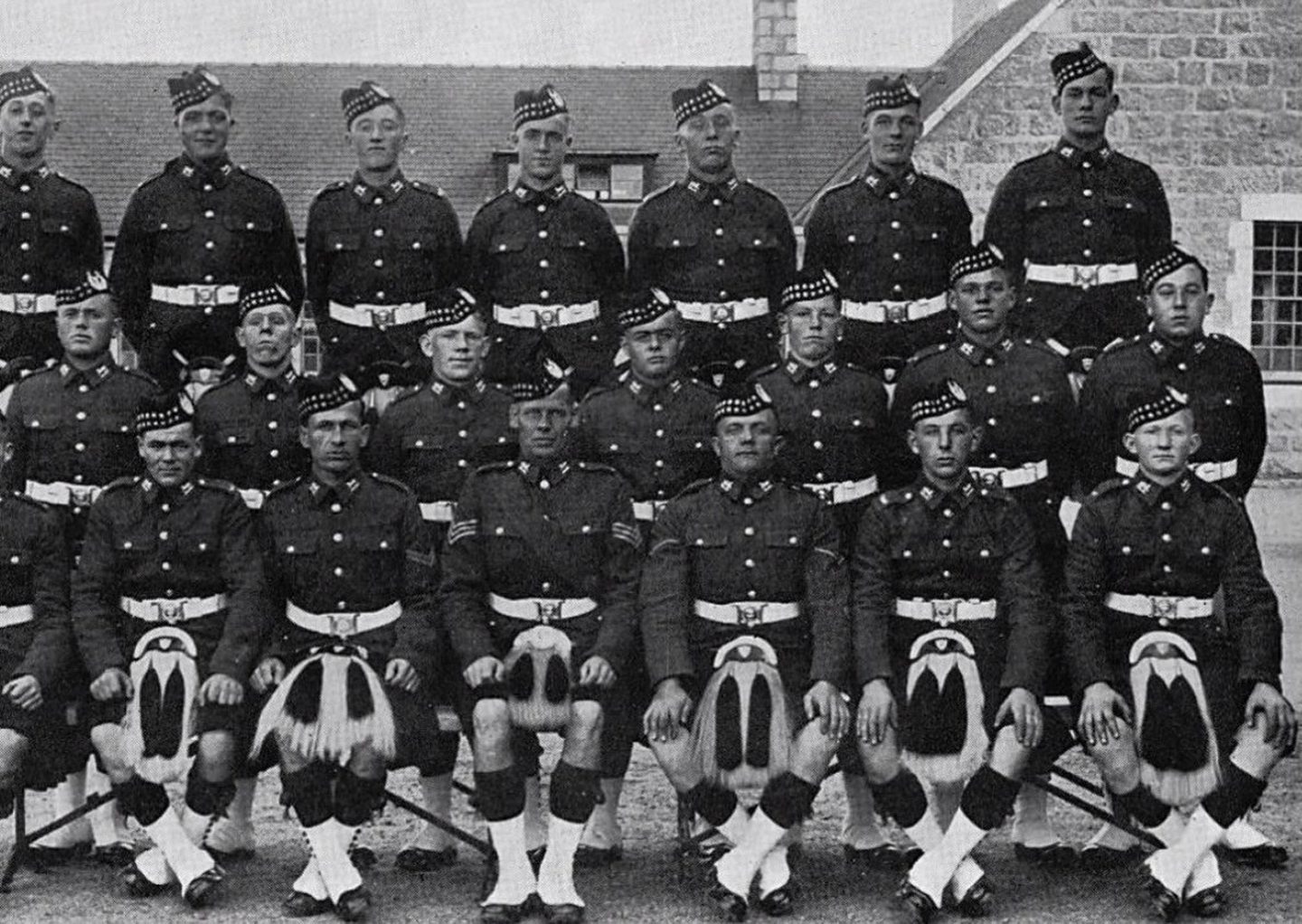

Yet, one of its main protagonists is William Fraser, a former pupil at Aberdeen Grammar School, who quickly made his mark in the Gordon Highlanders in the Granite city after being promoted to lance corporal in 1937.

He had plenty of the right qualities to justify his advancement – he was fit, had quietly-spoken confidence in his abilities, was an excellent shot and an expert in navigation. And, in these treacherous times, while the planet teetered on the brink of global warfare, he was very good at deception. As he needed to be.

‘Fraser was keeping a secret’

Petch says: ” When he had signed to the Army in 1936, aged 19, the doctor recorded that he had slight dorsal kyphosis, an imperceptible rounding of the shoulders, a defect so trivial as not to be relevant. But sometimes, in Army records, it is the subtext that is important – in this case, young Fraser wasn’t standing up straight and there was something about him which this doctor did not like.

“In fact, Fraser was hiding a ‘defect’, in the eyes of the British Army, indeed British society of the day – he was gay.” And, if that had come to light, it wouldn’t simply have ended his career, but probably led to him being imprisoned.

Devastating discovery

Thankfully, he was a convincing presence in every sphere which mattered in the years ahead. He was ready for action when the Gordon Highlanders faced one of the worst calamities in their history at Valery-en-Caux in 1940, where thousands of troops were either killed or captured and condemned to become PoWs by German forces.

He reported for duty at the Gordons barracks in Aberdeen on the last day of the Dunkirk evacuation, June 4, and discovered that his battalion hadn’t made it. Listening to the fate of his comrades on the BBC, he heard Winston Churchill’s fabled broadcast: “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds…”

It drove Fraser to keep pursuing new standards for himself and those around him, whether it was in Scotland, Europe or in the desert in Africa where he and so many of his colleagues were desperate to hunt down a man whom they viewed as their hated nemesis – Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel, the Desert Fox, who had presided over the surrender of so many Scottish soldiers at St Valery.

‘Unsung hero of the SAS’

His progress was remarkable as he and his fellow Commandos flung themselves into the fray with what we would now describe as SAS expertise. He and his men completed their training on Arran with harsh endurance runs – in full kit – to Goat Fell and Fraser swam in boots and full kit in the frozen Firth of Clyde. Soon enough, they were ready to embrace full-blooded combat, were prepared, precise, physically primed and passionately motivated. And, many made their impact felt for the rest of the conflict.

As Petch told me: “William Fraser is the unsung hero of the SAS – I served with the Regiment, and I had never heard of him [until he started writing this book].

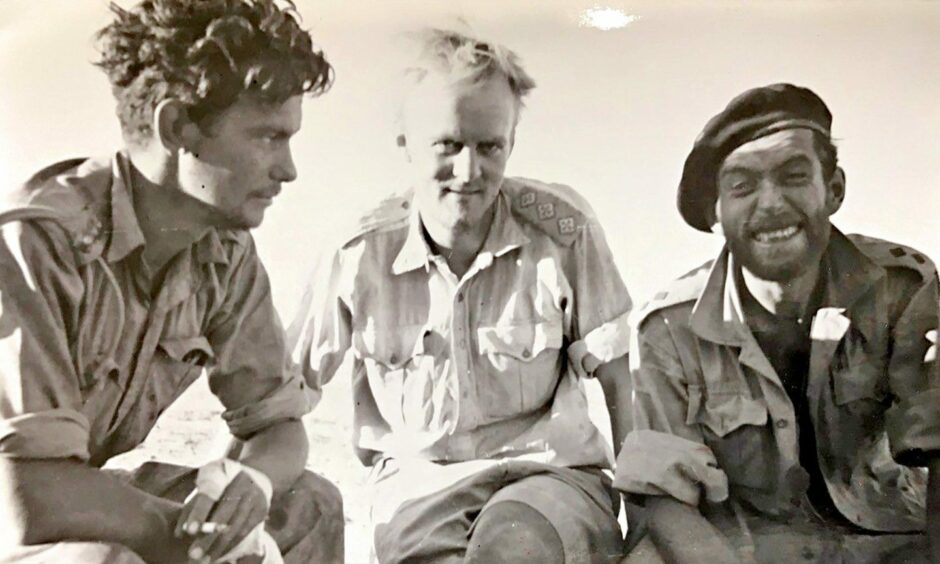

“My first insight was finding his combat report of the first successful SAS raid,

and realising the British press had mixed up two raids – his, and the Tamet airfield raid [in Egypt] which was carried out by [David Stirling and] Paddy Mayne.

Heroism deserves to be remembered

“Mayne is a legendary figure, but it was actually Fraser’s raid and destruction of 37 enemy aircraft that put the SAS on the map. His story is ultimately a sad one and it is evidence that bravery on the battlefield does not lead to happiness in peace.

“But the fact that he died in obscurity does not detract from this extraordinarily brave Scotsman. He was the most decorated of the original SAS officers, winning two Military Cross medals and the Croix de Guerre.”

There’s no need to dwell on what happened after the hostilities. In 1950, Fraser was charged with 30 burglaries, lost his army rank and finally gained work at a bakery without serving any time in prison. He eventually perished in 1975 from congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy and renal failure at the age of 58.

As Petch said: “The war killed Fraser; just not with a bullet”. But his exploits and heroism deserve to be remembered when they might have been forgotten.

And this book does a wonderful job of bringing it all to vivid life.

Speed Aggression Surprise is published by W H Allen.

Conversation