“Terra nullius”. This Latin expression roughly translates into English as “land that belongs to no one”.

We can shorten that to a phrase that is more widely used today – no man’s land.

But what is it? What is no man’s land? What happens in the middle, between two states? And most importantly, who is in charge? What are the international rules for such places?

One of the most famous examples of no man’s land incidents was during World War One. Christmas Day 1914 to be precise. There are various reports of what actually happened, but in a nutshell, there was a truce. German and British soldiers laid down their guns, left their trenches, walked into no man’s land, exchanged gifts and even played football with each other.

Utterly remarkable, and kind of restores your faith in humankind.

But, to me anyway, this fascinating episode just shows the ridiculousness of war. People who were, up until this day, killing each other, can then play football for a day – then go back to killing each other the next day.

Utter madness, and it just proves how far we have yet to evolve if we truly want to call ourselves a civilised species.

I’ve experienced being in actual no man’s land, often around highly contentious borders and/or unrecognised states.

Over the years, the bridge that divides the Albanian and Serb communities in Kosovo’s Mitrovica has been blocked by Serbs with everything from rubble and concrete, barricades, to even trees, plants and grass.

It’s impossible for anyone to drive over and has concrete blocks surrounding the north side.

Can individuals cross it? Yes, they can and do, but always during the day and for business purposes.

I was told that the majority of people always make sure they are back on “their” side come nightfall.

I was also told that many on both sides do not and never will cross over.

Policing here is extremely complicated indeed. An EU organisation called EULEX is responsible for enforcing laws on both sides of the bridge, but it is highly unpopular, especially in the north.

On and around the bridge itself and on the south side, NATO KFOR troops stand guard. But in the middle of the bridge, well, no one seems to know who controls it.

Last time I was here, when down at the bridge one evening, I asked a female Albanian Kosovo police officer who spoke English: “If I walk into the middle of this bridge, who is ultimately in charge here? You? The Serb officials on the other side, or the NATO guys on the bridge?”

“Good question,” she replied. Yet after much contemplation, she was not able to give a definitive answer. Therefore, standing in the middle of the bridge you see in my photo, you are technically in a no man’s land.

In northern Georgia stands the breakaway unrecognised republic of Abkhazia. Around the Georgian border it’s seriously run down, absolutely nothing here, apart from a border hut and an old shop.

A horse and cart covered in a wrap trundled by. It looked like something out of Little House on the Prairie.

My passport was studied, and I was told I could continue. I walked a few metres and exited Georgia. The only thing now between me and the unrecognised state of Abkhazia was a walk over the abandoned Enguri bridge.

Apart from a couple of very poor looking locals, there was no one else around. It took 15 minutes to walk over and I felt like I was in a scene from a classic cold war spy novel.

I stopped in the middle, I had left Georgia, but not yet entered Abkhazia, I really was in no man’s land. What’s the law here? Who is in charge? Technically, no one.

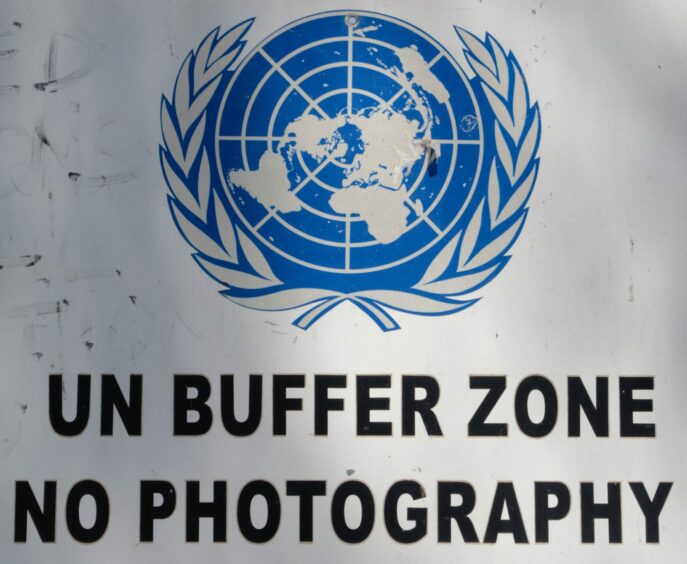

Divided since the 1974 war, there is swath of contested land bang in the middle of modern-day Nicosia. The Republic of Cyprus on one side, the unrecognised by the world Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus on the other. In the middle? A huge zone, surrounded by razor wire and soldiers.

A buffer zone between the two sides, a demilitarised zone, a no man’s land. I managed to get inside this no man’s zone for a quick photo, which according to the UN sign I should not have done.

The ultimate contentious divide is between Israel and the closed off from the world Gaza Strip. Armed with my all-important Israeli government press card, I’ve made successful trips in there, but on one occasion, after crossing into Gaza and after being held and questioned by none other than Hamas, I was denied entry and sent packing.

After being driven back to the checkpoint on the Gaza side, I walked slowly back through the one kilometre caged-in tunnel that separates Gaza with the dividing wall at Israel.

But on arriving at the Israeli wall, which has metal automatic doors built into the concrete, they were all shut, no one was around. It was near 3.30pm. Why is this important? Well, it’s the time every Thursday that Israel closes the Erez crossing completely. It does not open it again until 7.30am on Sunday.

Hamas were not letting me into Gaza, and it looked like Israel had shut up shop for 64 hours. Standing in the caged-in tunnel, it’s the ultimate no man’s land. I was not in Gaza, yet not safely back in Israel. I was nowhere.

I looked up the CCTV above me and raised my arms in a “some help would be good here” pose, then sat down and took a glug of water. My brain started to run wild – now wouldn’t that be a heck of a column for next week, “Stuck for 64 hours between Israel and Hamas…”

What are the rules here? Who is in charge? No one, it’s no man’s land in the middle of a war zone.

Suddenly a loud electronic beeping sound filled the air, a red light flashed and a door in the concrete wall slid open. An Israeli official appeared and gestured to me to come through quickly.

After numerous security checks and questions from Israeli officials as to what was going on with me, I was told regarding my predicament about being stuck in no man’s land for 64 hours: “We wouldn’t have left you there.” Good to know.

You may think that unless you go to some of the places I’ve been to, and I don’t recommend it by the way, that you’d never experience being in no man’s land. Well, if you’ve ever been in a transit lounge in an airport, you actually have experienced no man’s land in a kind of way.

Let’s say you take a flight from Aberdeen on KLM to America for example. You first have to fly to Amsterdam. You land there, and wait for your connecting flight. So, you’re in Holland, right? Well, yes, but also no…

You might be standing inside Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport, but because you’re in transit, you’ve not gone through Dutch immigration, not crossed the Dutch border, you are not really in Holland yet, and therefore in a kind of no man’s land.

What are the rules here? According to many experts, transit zones are part of that country’s territory, I get that, but the fact remains, transit areas are blocked-off areas for people who have not yet effectively crossed the border.

Transit areas are also the world over often used as holding areas for those who claim asylum on arrival at said airport. They are held there until the government decides what to do with them, ie let them enter the country or deport them. Therefore, once again, it is a kind of no man’s land.

There seems to be no standard rule here. The EU does not have a common policy regarding transit zones. So next time you’re in a transit zone, in say Paris airport, you’re not really in France. You’re nowhere really. Fascinating.

Talking about borders, when Putin invaded Ukraine, one of his excuses was to prevent Ukraine from entering NATO, and to protect Russia’s borders from the nasty west.

He’s achieved the exact opposite, because in response to Russia’s aggression, Finland has joined NATO and Sweden is in the process of also doing so.

What a spectacular own goal by the Kremlin.

Next week – From neutral to NATO…

Conversation