Aberdeen medical pioneer Mary Esslemont put her heart and soul into the National Health Service.

The NHS is regarded as one of the crown jewels of British society as it approaches its 75th birthday.

Despite facing unprecedented pressure in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, and being forced to tackle the problems of an ageing population and diminishing workforce, polls demonstrate it remains one of the most cherished organisations in the country.

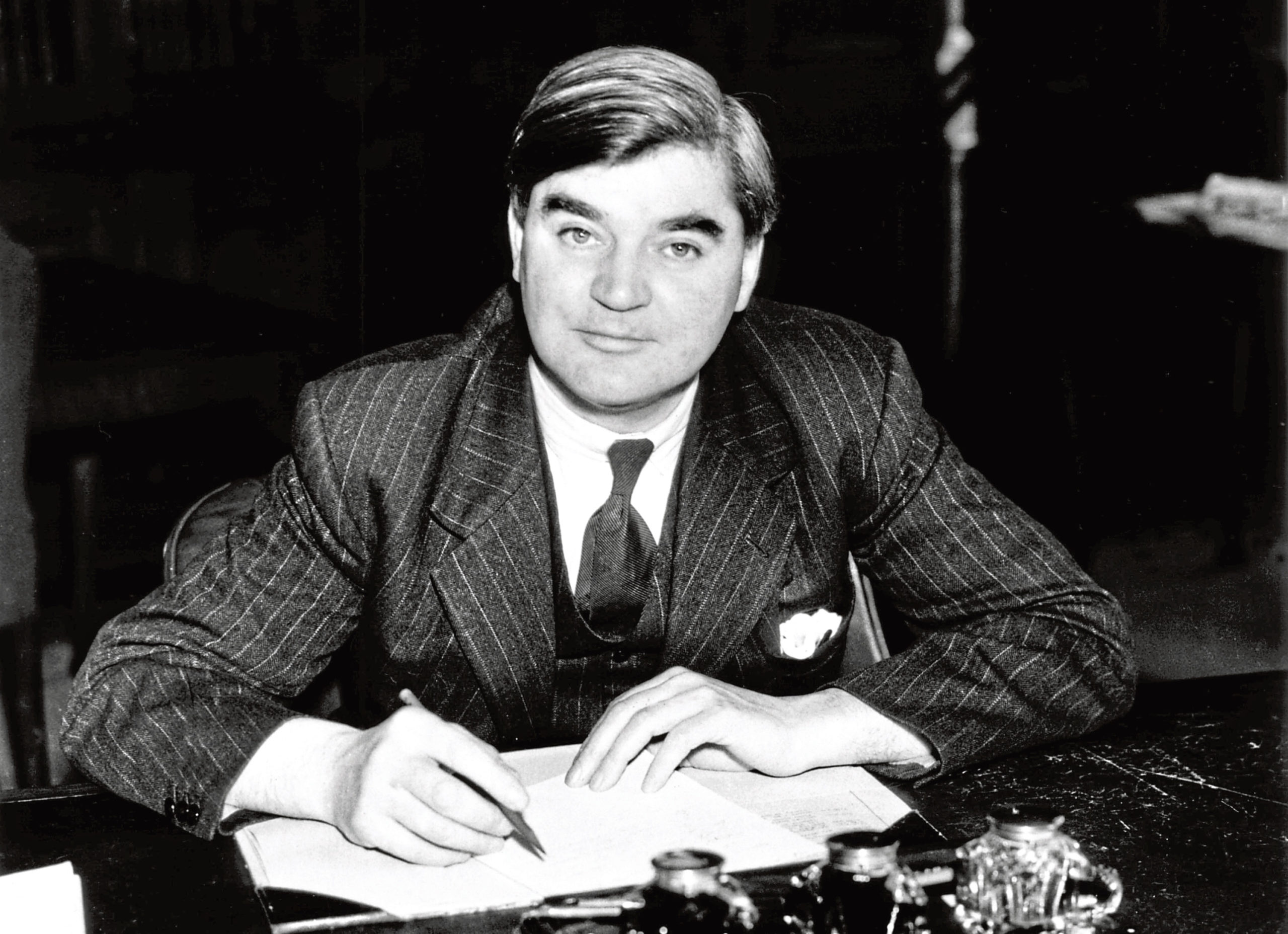

Even before it was introduced in 1948 by Secretary of State of Health, Aneurin Bevan, and backed by Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour government, the NHS was confronted with opposition from many doctors, those who felt it would cripple the economy, and others who simply believed it would inevitably struggle to cope with demand.

It was launched at a time of austerity

At that stage, the emphasis was on preventative medicine and improving the physical wellbeing of a nation which was run down by years of conflict, inadequate food supplies, rationing and the impact of a ravaged domestic infrastructure.

There was no consideration of mental health issues or post-traumatic stress disorder, though myriad soldiers returned from fighting in Europe and the Far East with psychological damage which haunted them ever after.

Since then, Bevan’s grand plan has become a victim of its own success. But looking back at its roots reminds us how much of the original plan was based on research and a report carried out in the north of Scotland before and after the two World Wars.

A blueprint for the NHS

The seeds of the NHS were sown with the publication of the Dewar Report in 1912 – named after its chairman, Sir John Dewar – which highlighted the desperate state of medical provision in the rural areas of the Highlands and Islands.

The committee gathered information by questionnaires sent to more than 100 doctors and methodically examined the situation in Inverness, Thurso, Kirkwall, Fair Isle and Lerwick; Lairg, Bettyhill, and Rhiconich in Sutherlandshire; Stornoway and Garrynahine in the Isle of Lewis; Tarbert in Harris; at Lochmaddy in North Uist; Dunvegan and Portree in the Isle of Skye; and at Kyle of Lochalsh, Perth and Oban.

This led to the creation of the Highlands and Islands Medical Service, which acted as a working blueprint for the NHS in Scotland. And Bevan, one of the most visionary figures in 20th century politics, recognised that, if a scheme could be implemented to help those in the north of Scotland, it could be extended to cover the whole of the UK.

So he and his colleagues knuckled down to making that a reality.

Jim Hunter, emeritus history professor of UHI, was born in the same year as the NHS. And, even now, he marvels at the revolution and how it transformed health and welfare.

He said: “The NHS, it’s worth recalling, took shape in a Britain that was hugely poorer than the Britain of today – a country reeling from the immense costs incurred in the course of its then recently concluded war with Nazi Germany.

They taxed the richest to pay for it

“So how, in the face of these grimly adverse circumstances, were Bevan and his colleagues able to make a reality of their vision of universally available healthcare?

“Because they did something that next to no mainstream politician is presently willing to contemplate. They committed themselves to taxes of a sort that tapped the wealth of richer segments of the population in ways that made some of this wealth available for purposes such as setting up the NHS.”

It was controversial. But the process was boosted by others such as Aberdeen medical pioneer, Mary Esslemont, who poured her heart and soul into the enterprise.

“No society can legitimately call itself civilised,” Bevan later wrote of his enduring achievement, “if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means.”

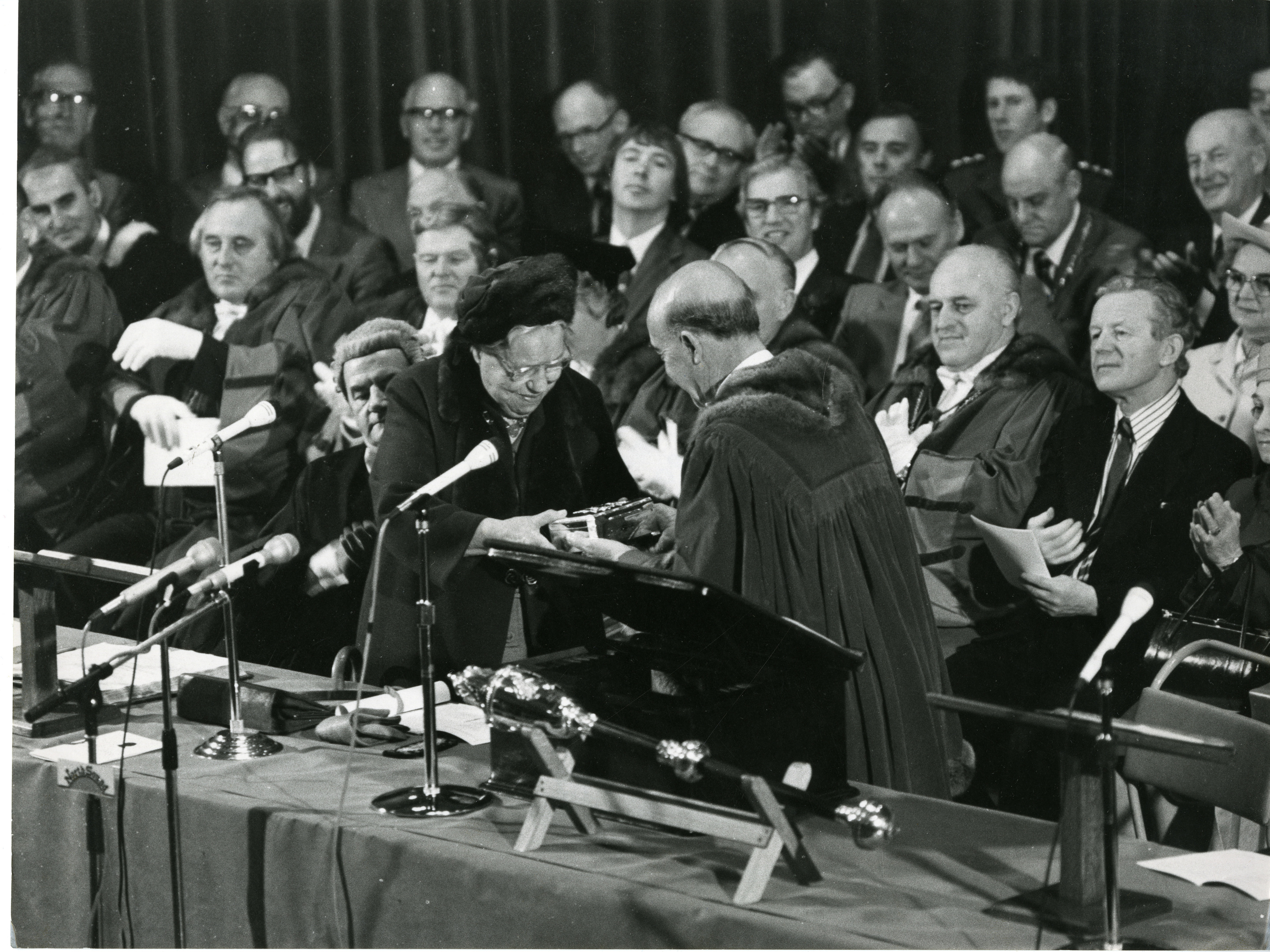

And these words were echoed by Esslemont, whose devotion to the NHS was unstinting throughout her life, which culminated in her being granted Freedom of the City in 1981.

After leaving Aberdeen University, the newly-graduated doctor became an assistant medical officer in Keighley in Yorkshire from 1924 to 1929. But she remained in touch with her former friends and returned home to become a GP in the 1930s.

When she was appointed as a gynaecologist at the city’s Free Dispensary, she noticed the poverty and illness which was endemic in many parts of the north-east and argued for a system where medical treatment was not denied to those who couldn’t afford it.

Devotion to the NHS

As the British Medical Journal later said: “Dr Mary was noted for her work with the city’s poor and underprivileged and for her activism for women’s rights.

“She gave remarkable service to the BMA, was a member of its council for 23 years and was the first woman to sit on the Scottish council in its history.

“Unsurprisingly, given her belief in the need for a better health system in Britain, she was always closely involved in the affairs of the BMA and was the only woman doctor to serve on the profession’s team which negotiated with Aneurin Bevan on the establishment of the National Health Service after the Second World War.”

Even by that stage, the NHS was coming under attack from those who criticised its alleged bureaucracy and wastage, as private health companies offered quicker treatment – for a hefty price – while recruiting and retaining staff proved a problem from the start.

Indeed, it wasn’t helped by the often ridiculous sexism which was a feature of the service from the earliest days and came to light in the pages of the Evening Express.

It recalled the memories of former nurse Eunice Hulse, who said: “We were not encouraged to have boyfriends. Our lecturers felt they interfered with our study.

“One of our lecturers came into the classroom and said that if anyone was hit by the love bug, they could leave now and not waste any more time.”

‘The best National Health Service in the world’

Mrs Esslemont always resisted any chauvinistic attitudes and, even as she received the Freedom of Aberdeen, focused on the broader picture of the NHS and how, regardless of its travails, was still something to treasure.

As the Press & Journal reported: “Dr Mary responded to the Lord Provost [Alex Collie] by saying she was delighted people’s health had generally improved and launched into an impassioned defence of the NHS and how other countries were interested in it.

“She said: ‘For 22 years, I travelled the world, attending conferences for the British Medical Association, and I had the chance to study the different health services which were being offered in many other nations. And, for all its faults and failings – which I hear about – I believe we have the best National Health Service in the world.”

She was not alone in that respect. And one suspects, even today, she would be championing one of the things which she helped to bring to fruition.