Robbie Shepherd never forgot his school years in Dunecht with their emphasis on correct grammar and “proper” English being spoken at all times.

He learned about Walter Scott and William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens and became well-versed in the Bible, even as he and his classmates sang hymns and anthems with the prevailing mantra – everything must be standardised, even if meant a dose of the belt for anybody who stepped out line.

As he later recalled: “I had only the one real complaint and that was the treatment meted out to our own Doric language. It was literally drummed out of us.

“When we were speaking in the playground, that was one thing, but as soon as we had entered the classroom, it had to change – completely. The only concession was one poem by Robert Burns and another by Charles Murray – just two poems in the whole of that time and I don’t remember any Doric prose being taught at all.

“It was part of the whole package – writing neatly, speaking English. But I do think a loss was involved. And now, there’s a great loss of the old words and of our ability to understand our own folk literature. That is a sad, sad aspect of the whole process.”

Yet, if it was an attempt to beat the loon out of the boy, it failed dismally. And Robbie, who died this week at the age of 87, spent the rest of his days championing what he described as the lyrically rich and wonderfully descriptive words and phrases, ballads and bothy tales which brought joy to millions of people across different generations.

An audience all over the world

He did it with a multitude of dance bands, going all the way back to the 1950s. There’s an old advert of him lined up to follow Chic Murray at The Tivoli. He did it when he was at Pittodrie watching his beloved Aberdeen, regarding his season ticket as a portal to paradise, especially when Alex Ferguson was in charge during the early 1980s.

And he did it at the BBC, where his ability to speak about Doric poets the way that Bill McLaren talked about rugby earned him an audience all over the globe.

At the outset, Robbie wasn’t convinced that his stint at the microphone would continue for very long, let alone 35 years. But, as Frieda Morrison, the chairwoman of the Doric Board recalled, he made the same kind of immediate impression as Jim McColl and George Barron did when they started presenting The Beechgrove Garden.

Frieda’s words testify to how this was another time, another place, in an environment where whole families sat round their radios and listened to music shows together.

She cast her mind back to an auspicious invitation in 1980 from the “legendary” Arthur Argo, who had created an agency called “Arthur’s Feet”, which propelled many well-regarded folk singers and musicians into the media spotlight.

They were ‘trying oot’ new man

As she said: “Arthur had just been appointed producer for BBC Radio Scotland and wanted me to come into the studio to be part of a new programme going out on air live.

“The programme was called ‘Haven’t Heard a Horse Sing’ and was to be presented by Robin Hall in Glasgow – and, as Arthur explained, by a new presenter whom they were ‘trying oot’ for the first time in Aberdeen.

“Well, the new presenter was a man called Robbie Shepherd. And this was my first introduction to the person who was to become such an important cornerstone of Scottish tradition and culture.”

‘He was known throughout the land’

Frieda added: “Throughout his broadcasting career, Robbie became the foundation which built a new audience that was new to Scottish music, but at the same time, he never neglected the generation which came before. That foundation provided the platform upon which Scottish music rebuilt itself and from which we benefit today.

“From that programme in the early 1980s, I had the pleasure of working with Robbie in a lot of different studios and different events and his professionalism and enthusiasm just didn’t waver or diminish over the years.

“We owe Robbie a great amount of gratitude for what he has done to promote Scottish culture and the north-east culture and language. He was known throughout the land and the world, as someone proud of faar he came fae – an the fowk he came fae.”

One of the most compelling facets of Robbie’s character was that he treated everybody exactly the same. There was no “radio persona” or role playing” wherever he performed.

One of his neighbours said: “He was just a lovely man, with a kind word for everybody”. Neil Simpson, the Gothenburg Great, whose involvement in the Dons’ European Cup-Winners Cup victory in 1983 earned himself sporting immortality, told me: “Robbie’s voice was a constant over so many years on a Saturday night.

One legend honours another

“My family knew him and his wife well. We met him many times and we loved his Doric chat. He was a lovely man and he will be a great loss to the north-east.”

But that was something which defined him from the days when he was growing up on the Dunecht Estate. Nobody was better than anybody else in a realm of Jock Tamson’s Bairns. So he could mix with Royals and attend grand academic functions, but he was the same down-to-earth individual who loved singing The Northern Lights, watching stock cars or revelling in an impromptu game of cricket, snooker or football.

Robbie was all too aware of the danger that Doric might wither on the vine and die out. Yet he fought for it, backed such initiatives as the Doric Film Festival – the brainchild of Frieda Morrison – and derived immense pleasure from the emergence of a new group of singers and writers including the likes of Iona Fyfe, Ally Heather and Shane Strachan.

Iona told me: “From the early 2000s, Robbie was a permanent fixture at festivals such as Strichen Buchan Heritage Society and Keith Festival.

He was so kind and supportive

“Getting to perform for him terrified me as a bairn, because in any room, you could just tell that he was a beloved and respected man, upholding tradition and encouraging the younger generation to participate in Doric poetry or singing or dance band music.

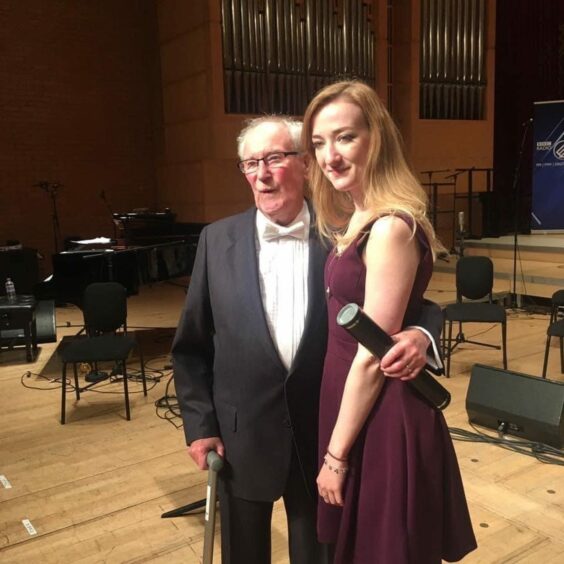

“He was so kind, supportive and encouraging towards me. In 2017, I was honoured to make a speech dedicated to him at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.

“I’m heartbroken at the death of a legend.”

It’s a long time since he first travelled by train after joining up for his National Service. But, true to type, Robbie had a story to tell about a near brush with disaster.

He said: “I remember getting on and walking up and down the carriages and finding this cafe halfway along where you could get a drink. I thought: ‘This is grand’.

“But then, I had to change trains and there was nearly a bit in the P&J to tell the world: ‘Homesick Dunecht loon throws himself off train in despair’. You see, I didn’t realise this second train had no passageway and I just opened the door and nearly fell out.”

‘We were all in this together’

Many years later, Robbie started writing a weekly column in The P&J which continued for more than 30 years. But he hadn’t changed from the youngster in Dunecht.

As he said: “In the village, we’d be in and out of each other’s houses all the time. The forester’s son or the painter’s daughter – we were all in it together.”

He lived by that philosophy. And we all share the grief at his death.

A poem in Robbie Shepherd’s memory by ‘Queen of Doric’ Sheena Blackhall

For Robbie Shepherd, Doric Champion

He wis a born broadcaster, screiver, maister o the Doric

On TV an on radio his programmes met success

At local gaitherins he wis socht, a couthie, skilled announcer

At Meldrum Sports an Turriff, as a compere he’d impress

Fowk mind on Takk the Fleer, The Beechrove Gairden, sheepdug trials

For aa o North East culture, Robbie Shepherd wis yer man

He screived Let’s Hae a Ceilidh, Dash o Doric, Doric columns

At the Braemar Royal Games, he welcomed spectator an clan

He wis gien a weel earned MBE fur heistin Scottish culture

The years rowed on, an thanks poored in for aa his dedication

Kings College it awardit him an honorary degree,

Thon Dunecht loon, a dynamo, a Doric inspiration

He sang as a performer wi the famed Jack Sinclair band

An later in his column in the P & J he strove

Tae champion oor bonnie airt in ilkie wird he penned

Luik ower his darg o mony years…Ye’ll find a treisur trove

The warld grows smaaer ilkie day, near smorin places oot

Robbie niver left his hame ahin, tae takk the gangrel’s pairt

Bit bedd, tae fecht his corner in oor muckle neive o lan

He kept oor wyes an spikk alive, an won the public’s hairt