It sounds like a Dore vision of hell, but it was a real-life tale of tragedy and tristesse whose reverberations extended far beyond the Second World War.

The Burney brothers, Christopher and Roger, both suffered their own privations during that dark period in history, but these bright siblings were victims of very different fates.

Roger, the younger of the duo, was a scholar and pacifist who nonetheless decided to fight against Nazism, but drowned in 1942 in the mysterious sinking of the Free French vessel Surcouf in what was the conflict’s worst submarine disaster – most probably caused by the devastating impact of so-called “friendly fire” from American bombers – and his passing was commemorated in Benjamin Britten’s famous War Requiem.

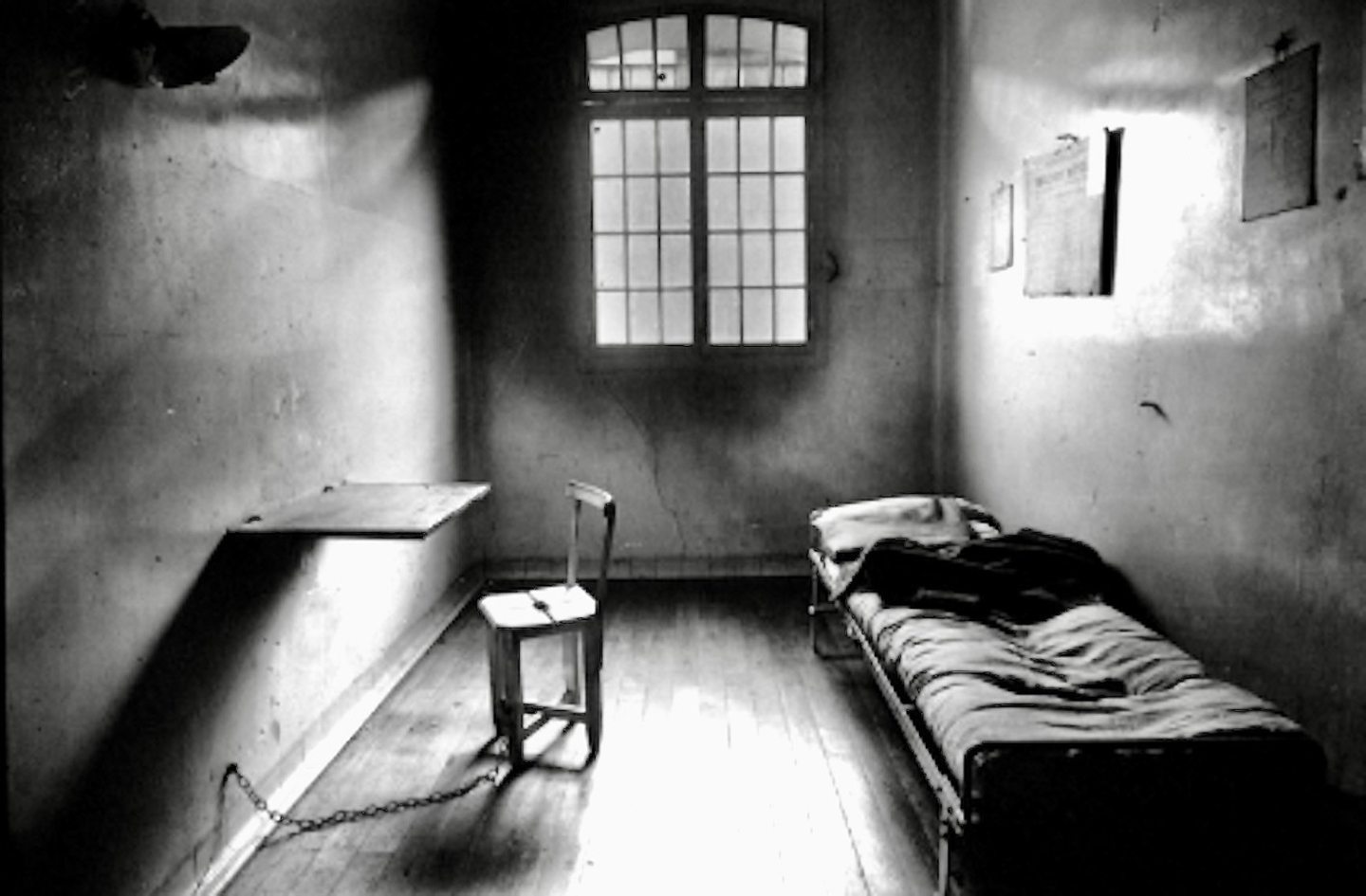

18 months in solitary confinement

Christopher was parachuted into France after being selected as an agent of Winston Churchill’s much cherished spy and sabotage ring, the Special Operations Executive, or SOE. In the same year, he was captured and tortured by the Gestapo spending 18 months in solitary confinement, never knowing whether every day might be his last.

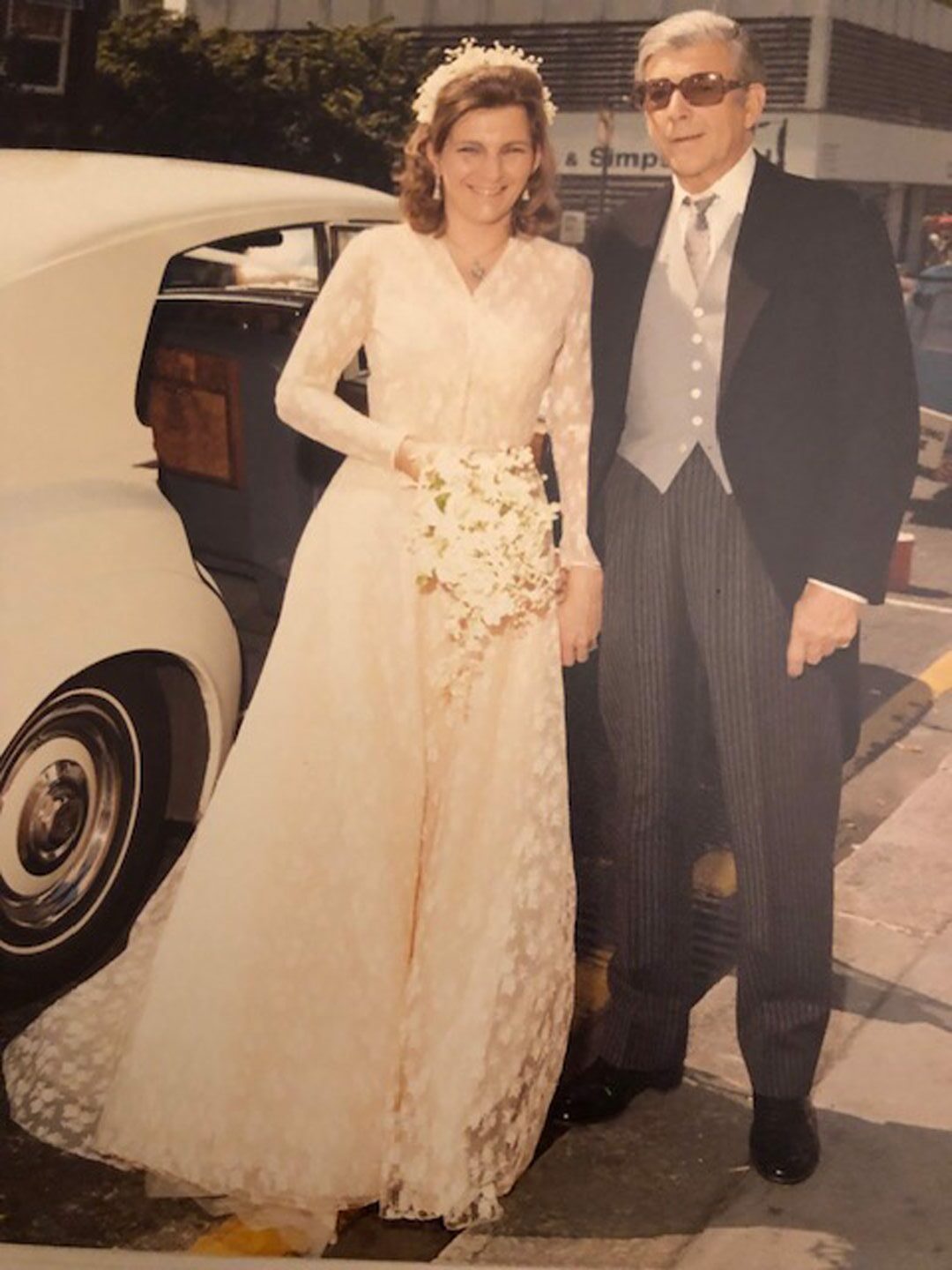

Initially, at least, it seemed that Christopher might find release and redemption when he was reunited with his sweetheart, Julia Burrell, one of three daughters of the wealthy clan which included William Burrell, the benefactor of the international art collection.

The pair had not spoken for three years when he phoned her in 1945, they met, and she inmediately called off her engagement to another man and married the former Commando who was proud of his Gordon Highlander roots and always described himself as “l’ecossais” even at his darkest moments in the bowels of incarceration.

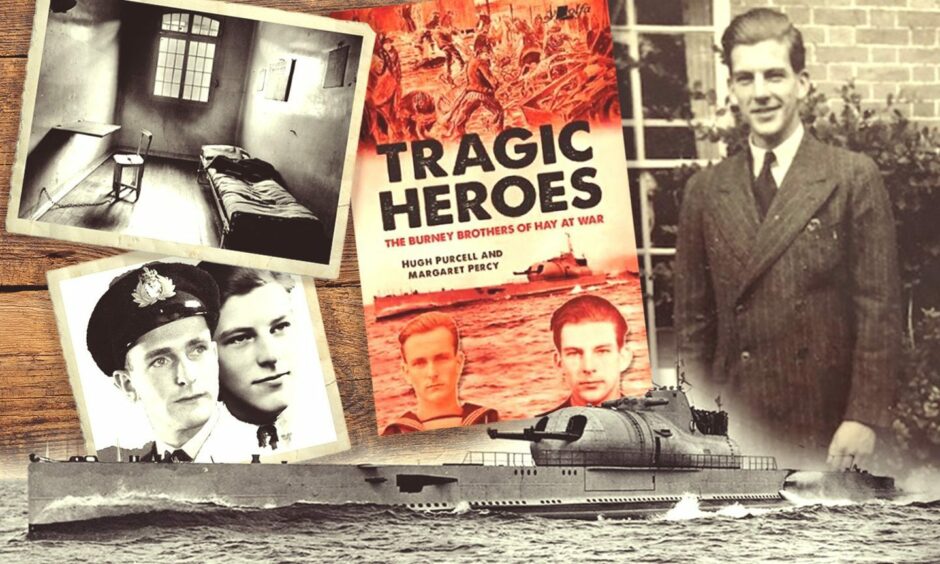

But, as a new book, Tragic Heroes, by Hugh Purcell and Margaret Percy makes clear, there was the opposite of a happy ending in peacetime after they were married and their daughter, Juliette, was born in 1947 [they also had a son, Peter, two years later].

At that stage, the family’s future seemed set fair. Christopher’s books, Solitary Confinement, and Dungeon Democracy, became classics of wartime writing, vividly conveying the squalid scenes, casual brutality and internecine warfare which often erupted between the poor souls who were squashed together in captivity.

Not allowed to talk about the war

The Burneys travelled to New York in March 1946 in good spirits. As Julia put it: “The cinema organ played at full throttle as we flew, hand in hand into the sunset of a promised land, unmarked by war, where hearts were warm and food was unrationed”.

Yet, as the book relates: “They were disappointed. Christopher found the job [as personal assistant to the Dutch Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, Adrian Pelt] frustrating and would no doubt have preferred to work for The Times or the BBC or the Foreign Service, all of which considered employing him.

“These were happy years domestically. Christopher was an adoring father and loving husband; Julia was admiring and always supportive. But the physical and psychological illnesses caused by Christopher’s war lurked under the surface.”

‘He had gone through so much’

In simple terms, he was suffering from post traumatic stress disorder which only, gradually manifested itself, while the British medical profession remained oblivious.

This brave man, who was recommended for a Military Cross and a Croix de Guerre – he had no interest in medals – hated talking about the war, in common with so many of his generation, and was laconic about explaining how he had endured such horrors.

In one instance, he replied: “I worked up to them gradually; it is not as if I went from this room to Buchenwald in a split-second. I’m sure madness would have been the result if that had happened.” Silence and the advice: “Ignore your nightmares” was the prescribed remedy for PTSD, but that meant that Christopher and his family had to deal with the consequences of the disorder taking its baleful effect.

And Juliette Paton, who now lives in Aberdeen, and will be at Aberdeen University next week for a discussion about the book and the Burney brothers, spoke about it to me.

She said: “My father was incredibly strong mentally and it took him about 15 years to react to his experiences and he suffered a massive nervous breakdown.

“Before that, he had had a couple of catatonic episodes when he just froze and we couldn’t get him to wake up. My mother tried to find out what triggered it but never could. He had gone through so much. There were only about 100 British soldiers sent to concentration camps, only about twenty came out, and only four survived.

‘He couldn’t cope with emotion’

“I was fourteen when my father became ill [in the early 1960s]. Not long afterwards, my poor mother also had a nervous breakdown.

“My father went to stay with friends in Guatemala and ended up staying away. It was difficult for me as my mother relied on me to unburden her misery on to. She also thought I could persuade him to come home, but I couldn’t.

“I also knew he couldn’t cope with emotion and my mother couldn’t turn it off. He and I had a special bond and we understood each other. When he went away, he apologised for going, but reassured me that I wasn’t at fault and nor was anyone else. Then, after Guatemala, he went to France.”

A reunion of sorts

Christopher was reminded of the power of art when he attended a performance of the War Requiem in 1963, which was dedicated, among others, to Roger Burney, the long-departed brother who had only been 23 when he lost his life.

Yet, a heartbreaking reminder of the insidious effect of his horrendous experience comes in a letter he wrote to Juliette, where he told her: “I’m sorry I’m such a messy father. I know it doesn’t make you happy, but I can’t see any way out.

“I wish to God things were different, but they’re not. Basically, anything I write to you is senseless. Birthday presents aren’t important, but happiness is. I would much rather you were happy, but I’m damned if I know what I can do about it.”

There was a reunion of sorts. As Juliette told me: “In the 1970s, he came back more and enjoyed seeing us all and his grandchildren.

“He was even going to come up to Aberdeen for Christmas [in 1980], but sadly fell asleep after lunch in his favourite chair at his club and never woke up. It was devastating for us, but so perfect for him to have such a peaceful ending.”

‘The balance will fall’

It was another time, another age, but nobody who reads Tragic Heroes will fail to understand why Christopher was so grievously affected. He had been strong for those who needed his comradeship inside Buchenwald. But he couldn’t just blank it out.

He asked a question at the conclusion of Dungeon Democracy which sums up his perspective on what he had witnessed during his lengthy imprisonment in conditions which we can (hopefully) thank our lucky stars we will never have to face today.

He said: “Now, we are at a crisis. In the next years, the balance will fall. On one side lies this idea of right, of reasoned self-discipline and a search for justice; on the other, evolution to a world of herds, led plunging and fighting for material gain by a few godless megalomaniac bulls.”

Some might argue his point is still as relevant today as in the 1940s.

The event, preceded by drinks, is in the MacRobert Building of Aberdeen University at 6.30pm on Thursday, September 28.

Tickets can be purchased on line from Eventbrite TragicHeroes_BurneyBrothersofHay.eventbrite.co.uk