It’s a discovery which has saved and enhanced the lives of at least 350 million people during the last 100 years.

Prior to its creation, countless children, diagnosed with the condition, were left facing a death sentence as their parents looked on helplessly. They could be made to feel comfortable, but medical staff could do nothing more to ease their plight.

And yet, the chances are that few will be aware of the prominent role played by a Perthshire-born, Aberdeen-educated scientist in the development and production of insulin, one of the most significant achievements in the history of medical research.

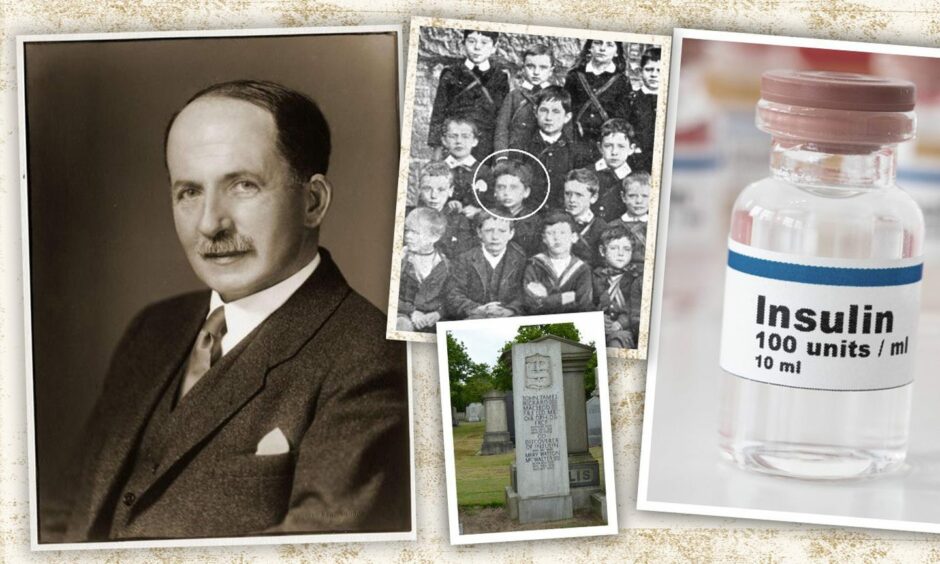

That’s because John Macleod was effectively airbrushed out of history for half a century. He was accused of hogging the limelight, of claiming credit for work carried out by other people when he was actually the catalyst for a remarkable breakthrough.

And when he left Toronto, where the insulin breakthrough was made, he is said to have been seen shuffling at the station and explained: “I’m wiping away the dirt of this city.”

But thankfully, if belatedly, his reputation has been restored, and a memorial statue of the great man will be unveiled in Aberdeen’s Duthie Park next week on October 12.

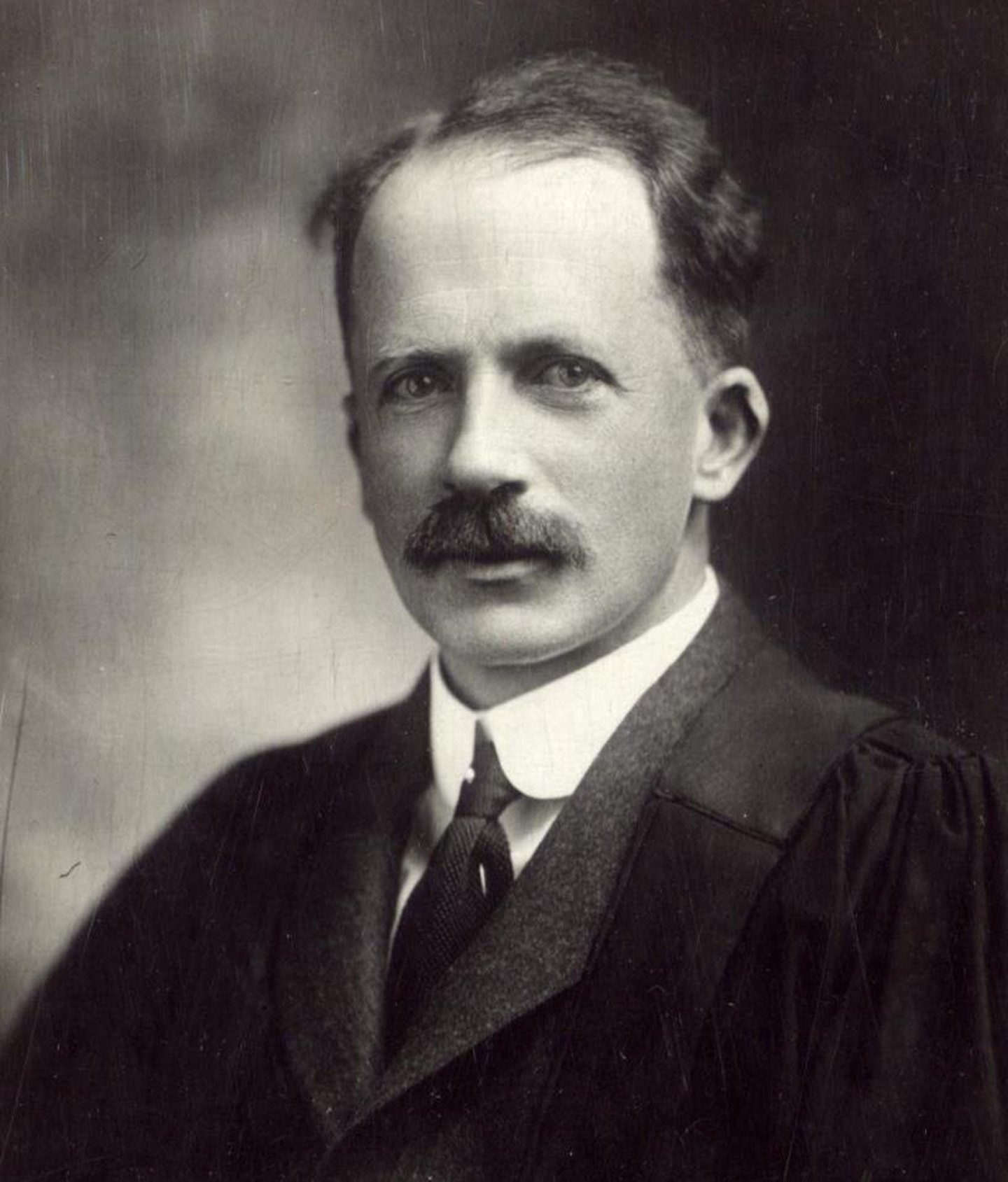

It’s no more than he deserves, because Macleod, a beetle-browed, intellectually brilliant fellow, was at the forefront of the trailblazing work which transformed the battle against diabetes after years of trials and tribulations, disappointments and disputes.

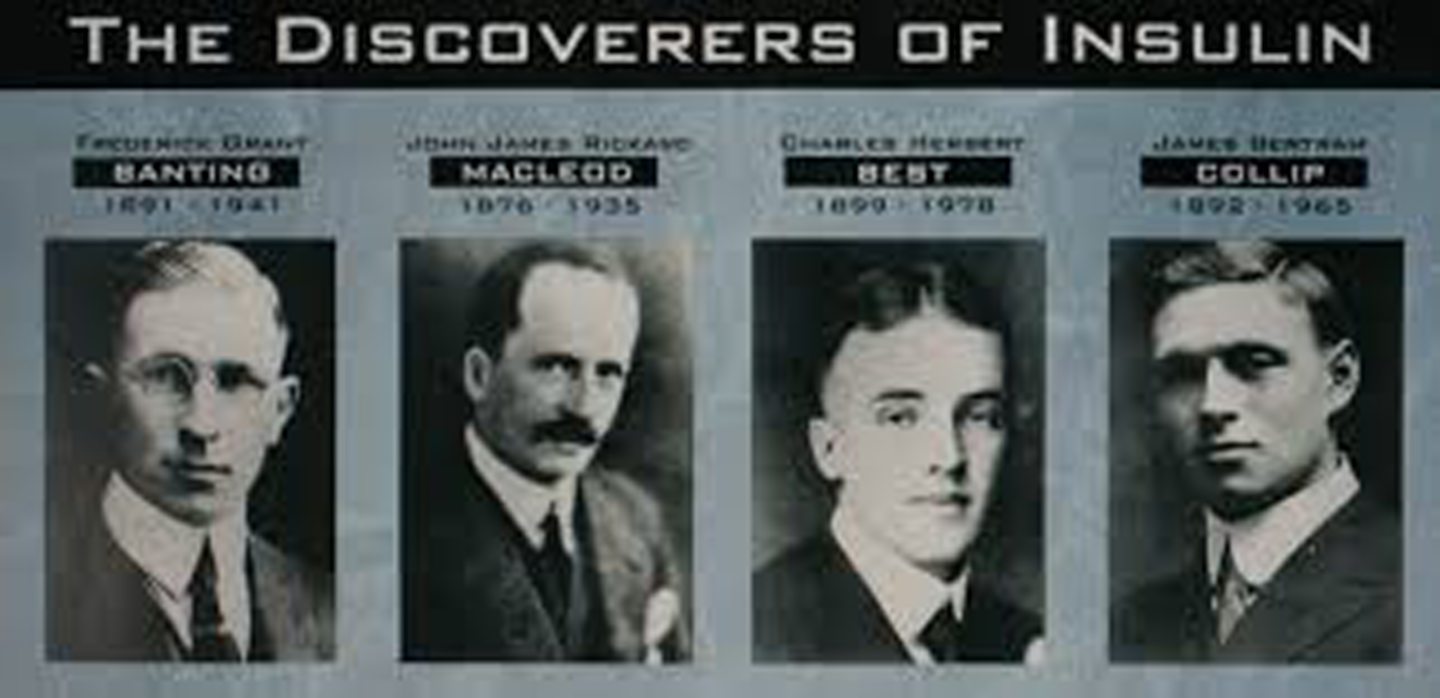

Professor Brian Frier, of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and an internationally-recognised specialist in diabetes, said: “The discovery of insulin is frequently and inaccurately attributed to Frederick Banting and Charles Best and, for decades, Macleod was effectively airbrushed out of medical history.

“The importance of the research of this quiet and self-effacing Scottish scientist cannot be over-estimated and he deserves to be as well-known to the public as Sir Alexander Fleming for his discovery of penicillin.”

Soon after his birth in 1876, his clergyman father, Robert, returned to Aberdeen and the youngster, who always adopted the approach that genius was an infinite capacity for taking pains, subsequently attended Aberdeen Grammar School and entered Marischal College at Aberdeen University to study medicine from 1893 to 1898.

Macleod worked until the sma’ hours

Much of the focus of Macleod’s life has centred on his work in Canada, but he was an apprentice physiologist in Leipzig and studied in his home city and in London, learning to teach and write textbooks and amassing the experience which were the catalyst for later partnerships with colleagues which yielded prodigious rewards in the early 1920s.

There are different perspectives on Macleod’s personality and how he interacted with others. It’s clear that he didn’t suffer fools gladly and was always the last person out of the laboratory in his early days while he was pouring himself into his work.

A serious-minded figure, he continued to pursue an academic career with a dedication which made him a great scientist, but not always the easiest human being to deal with in his day-to-day business.

The driven Scot was director of physiology at Toronto University, but there was no Eureka moment as he settled down to his work. This was real life, not a Hollywood biopic, so the building blocks of the new discoveries which changed the world for the better were only created after myriad hours in laboratories.

Dr Ken McHardy, a former consultant in diabetes with NHS Grampian and honorary senior lecturer at Aberdeen University, has studied his career in depth and acknowledges that Macleod’s journey towards insulin was long and meticulous.

It included both experience with many traditional techniques to study animal physiology and his expertise in the up-and-coming specialty of physiological chemistry.

He told the Press & Journal: “His research into experimental diabetes, first stimulated by working on a book chapter, led to several advances over 15 years of painstaking study. This put him at the forefront of world knowledge on the subject and with all of the necessary skills and experience to lead a major breakthrough.

There was no Eureka moment

“However, hundreds of researchers had been trying, and so far uniformly failing, to produce a treatment that could save diabetic lives.

“Despite work suggesting the pancreas gland may be the source of an important internal secretion, even this was unproven.”

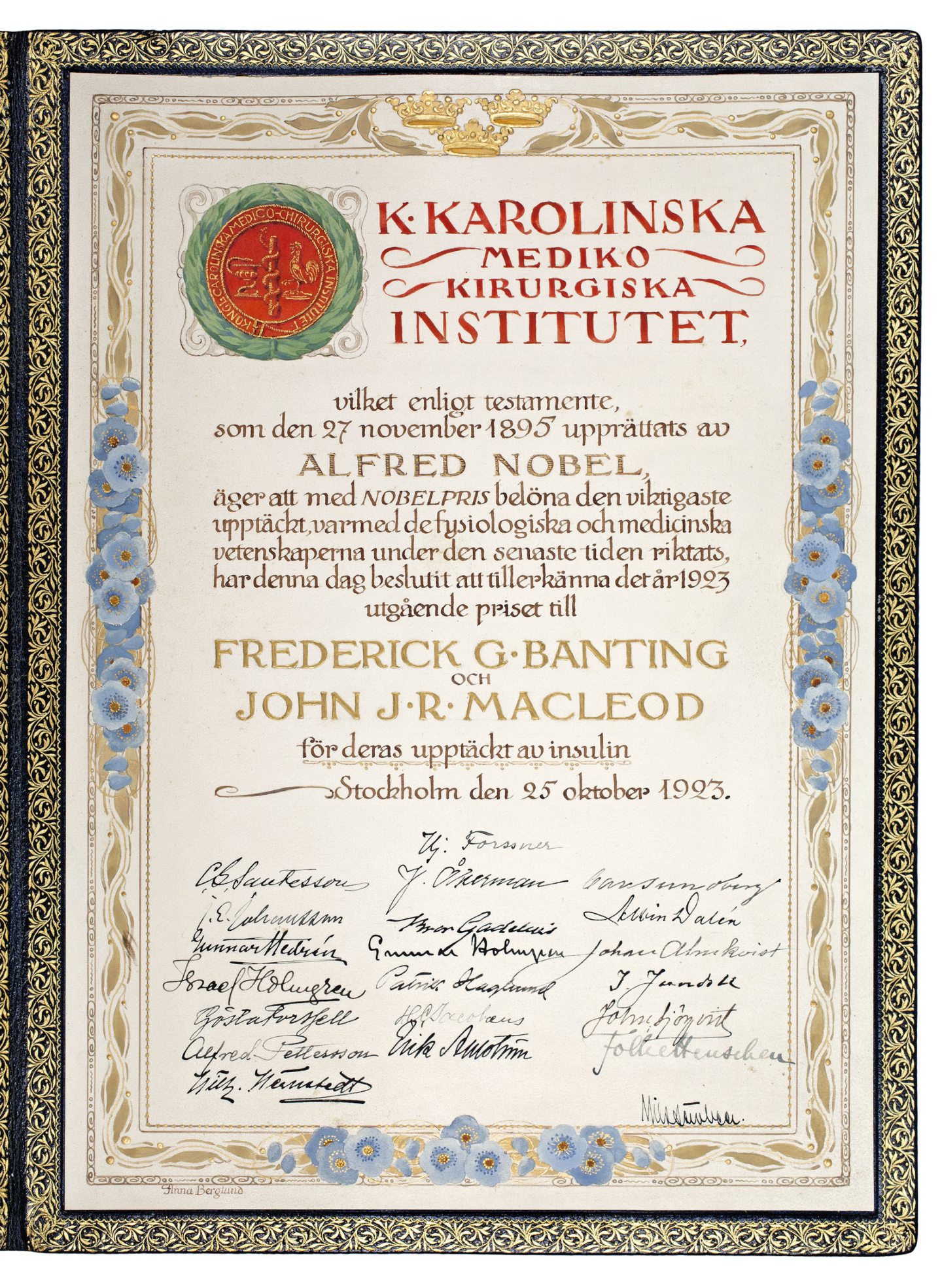

Few could have predicted the spectacular results which would materialise when he joined forces with students Banting and Best. Following their collaboration, Macleod received a Nobel Prize along with Banting, although he and the latter fell out over their contrasting claims of who had contributed most to the discovery.

It was an acrimonious climax to what had been an often fractious relationship between the pair and Macleod, unaccustomed to having to prove his credentials when he had demonstrated his excellence in Britain, Europe and North America, was understandably aggrieved at the ill-feeling which festered between the group.

At the end of 1920, the well-respected Macleod was approached by Banting, a young Canadian physician, who possessed a bull-headed drive and industrious – if often ill-considered – attitude to the research which later brought him fame.

He was a persuasive individual and even though Banting had virtually no experience of physiology, convinced Macleod to lend him laboratory space. The Scot also provided experimental animals and the assistance of his summer student, Best.

Banting and Best isolated an internal secretion of the pancreas and reduced the blood sugar level of a dog, whose pancreas had been surgically removed. They were excited, but Macleod expressed doubts about the results, borne from his greater experience.

Eventually, Banting accepted his elder’s instruction that further experiments were required before they could reach any definite conclusion, and even convinced Macleod to provide better working conditions and give him and Best a salary.

The next stage of their research was successful and the trio started to present their work at scientific meetings, which gradually built up momentum and publicity.

Macleod was a far better orator than his associate and Banting came to believe that he wanted to take all the credit for their efforts. But this notion was nonsense, as was demonstrated when the results were published in the February 1922 issue of the Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine.

Tensions ran high in the group

Indeed, the Scot actually declined co-authorship because he considered it was Banting and Best’s work: hardly the attitude of a man who desired to hog the spotlight. And yet, perhaps understandably, he was growing weary of the paranoia in the laboratory when, as he told colleagues privately, the priority surely had to be creating something which would save the lives of millions of people.

And there also remained the issue of how to get enough pancreas extract to continue the experiments. This convinced Macleod to extend his insulin research and recruit the biochemist James Collip to help with purifying the extract. Whereupon, significant progress was made after a trip to a local abattoir when they realised that pancreas extracts could be much more simply produced from fresh ox pancreas.

It was slow, methodical work, and Banting felt sidelined the longer it advanced. By the winter of 1922, this fragile character was certain that all Macleod’s colleagues were conspiring against him and Collip, who was increasingly frustrated with the tension in the laboratory, and threatened to leave because of the strained atmosphere.

Yet, amid these tensions, there was progress. In January 1922, the team performed a clinical trial on 13-year-old Leonard Thompson and it was soon followed by others.

As the news spread, so did the publicity about what had been achieved in Toronto. This was no dry scientific experiement; it was a life-changing discovery in the making and the sensationalist nature of the coverage reflected that sense of history being made.

Macleod’s presentation at a meeting of the Association of American Physicians in Washington on May 3 1922 received a standing ovation from the audience, because it appeared to indicate a major breakthrough was imminent, but obstacles still lay ahead.

At that time, demonstrations of the method’s efficiency attracted huge public interest, because the effect on patients, especially children with type 1 diabetes, who until then were bound to die, seemed almost miraculous.

Macleod was always proud of his part in the process. But, perhaps understandably, he had grown weary of the egos battling for supremacy behind the scenes.

He returned to Scotland in 1928 to become Regius Professor of Physiology at Aberdeen University and later became Dean of the University of Aberdeen Medical Faculty, where he continued to show his prowess in collaborative science, producing original research in tandem with colleagues at the Rowett Institute and in support of the Torry Fishery Research Station, while taking an advisory role to the Government’s Privy Council.

He encouraged scores of youngsters

Perhaps, just as importantly, he was renowned for his mentoring of a number of noted young scientists and engaged in prestigious lectureships on both sides of the Atlantic.

All this, despite the debilitating impact of rheumatoid arthritis, which had first affected him in Toronto and progressively limited his ability to travel and to work.

Dr McHardy, who has been advising the Macleod Memorial Statue Society for the last two years said: “Nothing should detract from the magnificent contributions of Aberdeen’s only homegrown Nobel Prize winner.

“We should remember and celebrate his reputation as a world-famous physiologist and educator with pride. He should, of course, always be revered for his single greatest contribution as the skilled and experienced impresario who led the Toronto team.

“Macleod’s leadership not only gave the world its first clinically useful insulin in 1922, but led the way to survival for millions with what is now known as Type 1 diabetes, and indeed existence, itself, for their descendants.”

This towering figure in his field died in 1935, aged just 58, and is buried in Aberdeen’s Allenvale Cemetery, across Great Southern Road from where the new statue will offer a permanent tribute to his feats. The sculpture shows him reading the pages of the P&J and, although he spent years in Canada, he always considered Aberdeen to be his home.

Aberdeen University is also dedicating the 2023 Carnegie Lecture to the impact of the former medical student on the treatment of diabetes and a blue plaque will be erected to commemorate his legacy.

A free public event, Celebrating 100 Years of the ‘Discovery of Insulin’ Nobel Prize, is being held on October 11, and will explore Macleod’s remarkable achievement with international diabetes expert Professor C. Ronald Kahn.

At long last, the world is paying him proper attention.

Tickets for the lecture, which runs from 6-7pm on October 11, are free, but places should be reserved in advance at abdn.ac.uk/events/19055

Conversation