Ali Cameron often regards the life of an archaeologist as having similarities to being a detective.

In both cases, you’re sifting through evidence, assembling little bits and pieces of the puzzle, and searching for a “Eureka” moment.

This redoubtable character worked with Aberdeen City Council for nearly 25 years, prior to setting up her own company, and she was previously involved in major digs at St Nicholas Kirk, Marischal College and the Carmelite Friary in Aberdeen, as well as discovering an ancient settlement at Cruden Bay, dating back to the Iron Age.

Yet few mysteries have taxed her resolve and resilience quite as much as the quest to find a medieval monastery in the north-east of Scotland.

This story has gained a mystique all of its own from the existence of the Book of Deer, written over 1,000 years ago, and the question of where these Latin and Gaelic texts were first scribed on vellum has attracted the attention of historians for centuries.

Discovering the missing Deer Monastery

Last summer, while the precious book – which is normally kept under lock and key at Cambridge University – was being exhibited in Aberdeen for the first time, a large-scale archaeological dig was launched by Ali and her colleagues, Alice Jaspars and Jan Dunbar, and backed by myriad volunteers, to track down the elusive Deer Monastery at a site in Buchan, 30 miles north of Aberdeen.

And now, following months of work by the team, as the prelude to their samples being sent for radiocarbon dating tests at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre in East Kilbride, they have been told some “unbelievable, but wonderful” news.

Yes, the “missing monastery” is missing no more.

BBC Alba documentary details the team’s work

Instead, one thing has become certain; there was a busy monastic community in Aberdeenshire going about its daily business long before the Battle of Hastings.

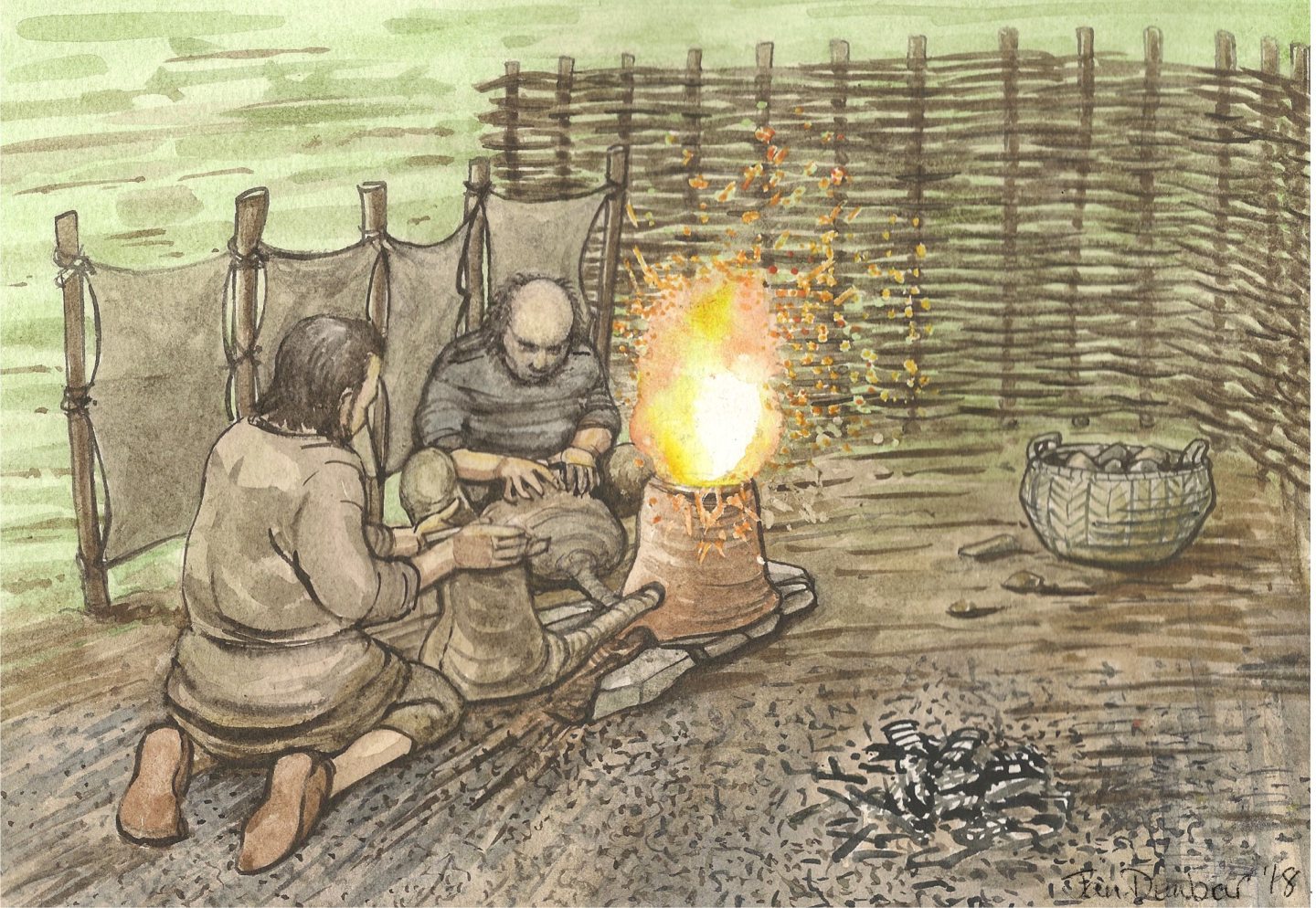

These men walked along a sturdy path to collect crops or pray, looked after their livestock, grew vegetables in their garden area and worked with metal, wood and charcoal in what was a self-contained environment.

The more educated of the monks wrote Scottish Gaelic texts in the margins of a book of Latin gospels – a volume which, even today, evokes astonishment from those who behold the words which are the first of their kind to survive for the next millennium.

And a new documentary, which is being broadcast on BBC Alba on Monday November 20, captures the endeavours of Ali and Alice as they venture through the full gamut of emotions from frustration and even resignation to the height of elation at the climax.

In terms of their reaction to their latest discovery – if we continue the detective analogy – Ali is like Ann Cleeves’ Vera, a veteran of her vocation who has seen almost everything during her time interacting with other people on cases.

Whereas Alice is more in the mould of Val McDermid’s Karen Pirie: a beetle-browed bundle of enthusiasm whose passion for her work leaps from the screen.

Both are overjoyed at the results

Yet that doesn’t mean their general response to receiving verification of the monastery’s existence differed from what you might anticipate, considering their efforts.

Ali told me: “I was very excited. We had excavated the postholes and they felt early but they could have been prehistoric or almost any period, and so when the early medieval dates came back – in an email from SUERC – I had to look over them several times to make sure that I had read them correctly.

“Then I went through and said to my partner: ‘We have found the monastery’!

Alice said: “I started out with Ali as a volunteer, before I began my studies, and it’s wonderful to see people who have been working with her for 15 to 20 years.

“In this instance, there was this horrible sense of waiting [for the test results]. Ali, ever so coyly, sent me emails and short Facebook posts and asked me to check them. And I did and it was just unbelievable. I had to double-check them because I couldn’t believe it was possibly true. Yes… the monastery had been there all those years ago.”

It all came together in the end

The group had been given the findings of the exhaustive radiocarbon dating process. These registered from 940-1020AD, from 952-1024AD, 1030-1160AD and from 1080-1154AD – all within the period which reinforced the existence of a monastery near to where an abbey was constructed several centuries later.

For Ali, it’s the close of a chapter in what has been a protracted bid to bring this to fruition. As she explained, any resemblance between the life of an archaeologist and Indiana Jones is purely in Steven Spielberg’s imagination. Hollywood has glamour and romance; this is more about getting down and dirty and being in it for the long haul.

She explained: “I was contacted in early 2017 when the previous archaeologists involved in the site had decided not to continue to be involved.

“I knew about the project looking for the monastery, but quickly read as much as possible and started walking areas around Old Deer to look for likely locations.

“When we went into the field where we excavated in 2017, 2018 and 2022, I had a feeling that this was a likely spot. There was a terrace which dropped off to the river.

“But I have had feelings about a site before which proved not to be an important site, so we kept our heads and started our research. We commissioned Susan Ovenden and Alistair Wilson from Rose Geophysics in Orkney to carry out ground radar and resistivity surveys of the wider area including the area of Deer Abbey.

Some fascinating features found in dig for missing monastery

“Because the area had been cultivated by [James] Ferguson of Pitfour [who became Dean of the Faculty of Advocates in 1760 and was elevated to the bench as Lord Pitfour in 1764] for his walled garden, there was a depth of soil over the site and so the results were unclear, but there appeared to be features of interest in the higher terrace area.

“We dug and found fascinating features from the first year and so that’s why we went back to open increasingly larger trenches.

“The site is very disturbed and so huge trenches in 2022 were opened to cover as much of the area as possible looking for trace remains. We could not have done this without my fantastic co-directors Alice Jaspars and Jan Dunbar and the volunteers who work so hard, are so passionate and even camp on the site and work into the evenings!”

A strong sense of camaraderie

The programme highlights the strong sense of comradeship and camaraderie which built up between those involved in the dig, including students from Aberdeen and Glasgow universities, visitors from as far afield as the United States and members of the Book of Deer Project group in Mintlaw.

There’s a touching scene towards the conclusion when Premala Fawcett sheds tears as she bids adieu to her friends at the site, and when she and Ali exchange a big hug, it serves as a recognition of how this energetic volunteer had helped uncover evidence of a path – one of the pivotal parts of the hunt for the monastery. And why? Because there wouldn’t have been a path without people wanting to travel from A to B.

These clues gradually helped the team to delve further as the clock ticked down on their quest. Even in the last few days, there was at least one moment where they seemed destined to be thwarted, but thankfully, these are diligent, resourceful people and, eventually, they found enough postholes to map their way to a positive conclusion.

So what does Ali believe life would have been like for these medieval monks? Having talked to other experts, she has no doubt it would have been challenging, especially during the long dark winters in this Buchan locale.

She said: “You would have needed a lot of different trades, so it was almost like a village. They would have had to be self-sufficient and done pretty much everything for themselves, whether it was in workshops or the garden or the blacksmith’s forge.

This was a mini medieval village

“There would have been people here who would have been completely covered in charcoal, with singed eyebrows and burned hands – and that is something which archaeology is really developing these days; thinking about the individuals who worked day after day in what were probably awful conditions.

“But this is incredibly important. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get a look at an early medieval monastery and you can see what it means to us.”

The area has now been restored to nature and there are fields where there were trenches last year. But it’s likely that archaeologists will extend their investigations in the future and discover more about the magnitude of the Deer monastery, a sacred place with a history stretching all the way back to St Columba who lived from 521-597AD and spread Christianity through the north of Scotland.

Digging at Deer Monastery hasn’t ended

Ali told me: “The site is now well protected with a depth of soil and in an area that is not cultivated at the moment. But, now we know that this is a small part of a much larger monastic area, I’m sure that there will be further work in the surrounding area.

“Does the monastery go as far as Old Deer, for example? The terrace along the river runs to Old Deer to the east and also the west.

“A widescale geophysical survey might help to start working out the size of the monastery and then maybe lead to further excavation in the future.”

It’s an engrossing tale for lovers of the past. And one suspects that Ali hasn’t stopped using her little grey cells.

Làrach Leabhar Dhèir (The Missing Monastery) is on BBC ALBA on Monday November 20 at 9pm.

Conversation