Pat Macleod can remember the days when pupils were belted in classrooms for the “crime” of speaking Gaelic.

And the TV producer from Lewis has heard all about how successive generations chose to talk to their children at home in English, so they would “do well in school”.

The impact was dramatic in terms of treating those who clung to their heritage and traditions as being near pariahs and the decline in speakers, since the 1872 Education Act inflicted a harsh ban on Gaelic being spoken in schools, has led to a situation where fears have been expressed about the language’s very survival.

Innovation to ensure survival

Yet, if some educationalists strove to curb its use – along with Doric – in a misguided bid to adopt a one-size-fits-all approach across Scotland, other bodies and individuals have launched their own rearguard action which is paying dividends.

And while nobody is pretending there aren’t issues in ensuring Gaelic flourishes in the future, there is sufficient impetus and innovation to suggest it’s not going away quietly.

The 2011 census revealed there were more than 57,000 Gaelic speakers in Scotland – results from the 2022 census are still being published, with the first release of results taking place in autumn.

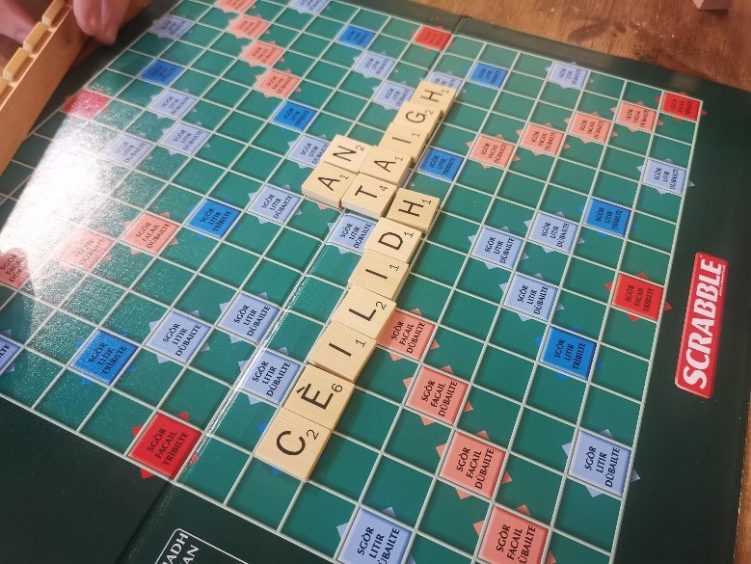

Recently, it emerged that the word game Scrabble will be available in Gaelic for the first time. The new edition features 18 characters, rather than 26, because the Gaelic alphabet does not use the letters J, K, Q, V, W, X, Y or Z.

The grave accent, a mark indicating that a letter should be pronounced a particular way, also appear on the vowels À, È, Ì, Ò and Ù.

Keeping the flame alive

The Stornoway-based cultural centre and community cafe, An Taigh Ceilidh, worked with Tinderbox Games in London to license the new version of the game.

It is just the latest way of spreading the word – or indeed thousands of them – about Gaelic, whether in the success of TV channel BBC Alba, the translation of computer games and such novels as the Harry Potter series into the language, and bite-size lessons being available on the Duolingo app, which has international appeal.

These initiatives have been welcomed by Pat, who argues passionately that many other parts of the globe seem to have less of a problem with Gaelic than Scots themselves.

She told the P&J: “Like any language, it is much more than a way of simply communicating words, it is a whole culture. For some reason, people from the rest of the world respect and understand this much more than non-Gaelic speaking people in our own country, whether it’s through ignorance or feeling threatened, I don’t know.

We are not going away

“Gaelic is in the very fabric and DNA of Scotland. I am aware of more place names around me in Aberdeenshire with Gaelic roots than where I grew up in Lewis where Norse names dominate. Gaelic roadsigns aren’t a political statement, they are about keeping alive why a place is called what it’s called.

“So we need to help speakers feel confident about using the language without judgement or mocking. Gaelic, like Doric, might be a minority language but minority doesn’t mean inferior, it simply means there are fewer of us.

“If we don’t save Gaelic in Scotland, it won’t be saved anywhere.”

There is a dearth of specialist teachers, an issue which is currently being addressed, but many Gaelic aficionados are more positive now than they were 20 or 30 years ago.

Award-winning author Donald S Murray told me: “I’m much more hopeful about the future of Gaelic than my father’s generation would have been when they were young.

“In schools throughout the Highlands and islands, and even sometimes in Scotland’s cities, they would have their knowledge of their tongue whacked out of them. There is still, unfortunately, a legacy remaining from that time, though it’s mainly found among Scotland’s monolingual population.

It enhances the quality of life

“One of the traits that always astonishes me is their ignorance of language. I recently read an individual claiming there was no Gaelic influence to be found within Edinburgh – his eyes are clearly clamped shut when he stamps around districts like Dalry, Balerno and Corstorphine. In that way, he resembles some drivers when they spot a Gaelic road-sign. Their sight darkens and they become more lost and confused than ever.

“One of the many benefits of being a Gaelic speaker is that you gain a greater awareness of the nation’s history, folklore, music and landscape. Bilingualism also adds to your awareness of the rhythms and structure of language. One of the reasons why so many of Scotland’s greatest writers – from George MacKay Brown to Norman MacCaig and Alistair Maclean – come from a bilingual background is that Gaelic enriches both a young person’s tongue and hearing. It also enhances their lives.”

There is certainly no sense of despair at Sabhal Mor Ostaig, the national centre for Gaelic culture and learning, which is based in Sleat on the Isle of Skye.

On the contrary, the principal, Dr Gillian Munro, is a fervent champion of the language and highlighted the increasing amount of interest in it within her establishment.

She said: “We are optimistic about Gaelic’s future, especially after welcoming our highest number of Gaelic students ever in the last year, with 1,600 students learning both on campus and online.

Positivity tinged with caution

“Maximising exposure to the language, both in the community and in education, is key to Gaelic’s development, and that’s what we do best with our immersive learning opportunities at Sabhal Mor Ostaig.

“We promote language use through practice and participation as part of a wide range of Gaelic courses and courses through the medium of Gaelic in music, culture, teacher education, the media and more.

“Those world-class immersive learning, research and cultural opportunities are key to creating a new generation of confident Gaelic speakers.”

A feeling of positivity, tinged with caution, seems in evidence throughout the Gaelic diaspora. Ultimately, regardless of the problems which caused a decline in the 20th century, it does genuinely appear there are reasons to be cheerful.

A Scottish Government spokesman told me: “Gaelic is a significant part of Scotland’s culture and we want to ensure it can thrive and grow.

“We will present the Scottish Languages Bill to Parliament during this Parliamentary year to help promote, strengthen and raise the profile of both Gaelic and Scots.

Significant rise in Gaelic teachers

“The Scottish Government is committed to supporting access to Gaelic Medium Education for those that wish to have it and Gaelic teachers are vital to this success. There has been a 24% increase in those currently teaching Gaelic in primary and secondary schools between 2018 and 2022.

“We are continuing to work with a range or partners, including the General Teaching Council Scotland, Initial Teacher Training Institutions and Bòrd na Gàidhlig to create pathways, such as the new Gaelic Additional Teaching Qualification (ATQ) at the University of Strathclyde, for those who wish to enter the sector.”

What else can we say but “sin deagh naidheachd?”

Or “that’s good news” for those who value Gaelic as an enduring part of Scottish life.