There was a definite sense of ignorance being bliss around Caithness during the worst years of the Cold War from the 1950s to the 1970s.

And nowhere was that more obvious than in the activities of the US Naval Communications Station Thurso and the sight of a radio mast called The Big Stick.

This loomed large in the landscape – after all, it was more than 600 feet tall – and many local residents wondered about its purpose. Yet few could have guessed the grim reality that its job was to broadcast messages to American submarines in the Northern Seas.

A direct link to the White House

These communiques were one-way only; there was no need for anybody to reply because these were the instructions for a nuclear missile launch.

And, even more chillingly, it was this unassuming base in Thurso which would relay the US president’s command to fire the starting gun on a potential Third World War.

Thankfully, despite such incidents as the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962, when the world stood on the brink of the precipice, diplomacy prevailed over bombs.

But, in several cases, it was a close-run thing as tensions were ratched up between the more hawkish elements of cold warriors on both sides of the great divide.

A vital location

David Mackay, a former Special Forces Officer, has brought his expertise to bear in telling the story in Bubbleheads, SEALs and Wizards of how the American military presence in Scotland during the Cold War was greater than in either of the World Wars, bringing with it the largest peace-time number of foreign military personnel in history.

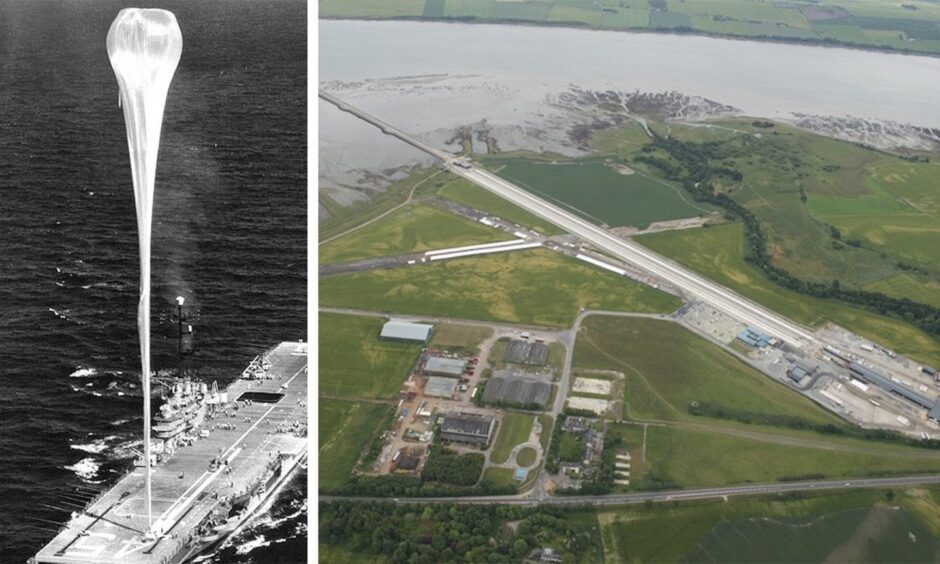

And while there were outlandish attempts to infiltrate the Soviet Union through the deployment of giant balloons, scores of which were launched as part of Project Genetrix from Evanton in Easter Ross, in addition to the regular arrival of Russian spy trawlers in Ullapool, there was no disguising the gravity of the situation.

In simple terms, Scotland was an active centre of US strategic operations with a vital geographical location. It was close enough to the Soviet Union to be a launchpad for NATO’s nuclear weapons. But equally, it was in the crosshairs of Russian bombs which would have caused annihilation throughout the Highlands with targets such as the Holy Loch and the stations at Thurso, Edzell, Kirknewton and Machrihanish.

Mr Mackay has investigated the background to how the Thurso station would have functioned in the event of the beginning of nuclear hostilities.

He said: “If the president decided to start the firestorm, the order would go out via the Big Stick. On receipt of the message, SSBN [ship submersible ballistic nuclear] commanders would commence the firing sequence.

Civilisation would be laid low

“The missiles, ready in their tubes, could be launched within 15 minutes, programmed to head to Russia, with their target details locked into their guidance system.

“The nominated officers would vote to proceed with the launch and mayhem and annihilation would follow. Millions of people would be killed, cities would be destroyed and civilisation would be laid low.

“It was Thurso’s personnel who made this scenario possible. The base was a vital stage in the process of creating nuclear devastation for Russian cities – and for everyone at Thurso as well.”

That was the reality which bubbled beaneath the surface; the fear that if a nuclear conflict started, it would escalate and Scotland would be directly in the firing line.

After all, as Mr Mackay has illuminated in his new work, pertinently highlighting why CND attracted so many new supporters during the Cold War decades, the country was the perfect fit for America’s perimeter defence policy.

As he explained: “Scotland would take the initial Soviet attack. This would give Washington additional time to increase its readiness and take steps to de-escalate tension. The Soviet missiles had a limited range, but could easily reach Scotland.

The troops had no idea of big picture

“The American military personnel operated to a high standard of professionalism, but apart from those at Holy Loch, most of them had no idea of the perilous situation their presence had created for the local Scottish communities.

“From those Americans’ point of view, they were defending the United States. And Scotland was part of the process.” It was never said, but it was dispensible.

Yet, in the early days as the Iron Curtain slammed shut on global affairs, Western powers were desperate to know what was happening behind the closed borders of the Soviet Union. They devised various options for infiltrating the enemy defences and one of their most novel solutions was low-tech and unleashed from the north of Scotland.

Though it sounds like something from the X Files, the United States Cold War spy balloons venture – known as Project Genetrix – was wheeled out in in the mid-1950s in a genuine attempt to discover covert information about the USSR by taking photographs from the sky with high-resolution cameras.

Not that it was promoted as such. Instead, a short news story in the Aberdeen Evening Express on August 10 1955 reported: “The RAF and USAF announce that a small research station will be set up this month near Evanton, Ross-shire, for the purpose of launching high altitude meteorological balloons.”

It caused a stir in the region

The operation began in June 1955 when a detachment of Americans arrived to check the suitability of the location. More than 120 moved to the base a few months later.

The hardware was sent by ship to Invergordon, as the prelude to being unloaded and transported to Evanton in trucks. The huge movement caused quite an impact on the local population, who had never seen so many trucks before. Buildings even shook with the vibration of the heavy traffic.

The initial balloons were sent into the sky on January 10 1956, but the weather intervened to sabotage the venture and Evanton was seriously hit by wind and snow. There were other issues; the cameras they were carrying could be detected by Soviet radar and the silvery devices were often mistaken for UFOs.

Some might have been aimed at Russia, but met an ignominious fate. Many of the balloons did not launch successfully and crashed into local farmers’ fields, as well as into the Cromarty Firth. But, eventually, there was one successful foray.

It was launched on Burns Day

Mr Mackay said: “On February 1, the crew of a beavertail C-119J aircraft spotted a balloon parachute at 18,000 feet above the Pacific Ocean. [Finally] the thumbs-up signal was given to the cockpit and the plane peeled away for home.

“The Evanton adventure had been vindicated.

“The balloon had been launched on January 25 – [Robert] Burns Day, the Scottish national celebration. Perhaps that was its inspiration. Because, when it was recovered, it had travelled 158 hours and 22 minutes from Evanton and, from the camera package, 900 feet of film had been exposed, providing more than 10,000 usable photographs.

“And that was it. This was the only successful balloon from Evanton – a success rate of 1%. Scotland’s strategic value had been demonstrated.”

Most of the items failed

However, one of the USAF personnel, Mike Brady, confirmed the scale of the problems throughout the whole initiative when he said: “The work was straightforward. We launched balloons on a regular basis, but a great many of them failed.”

Several of them crashed in an 80-mile arc stretching from Dornoch through Invermoriston, Blairgowrie, Inverurie and Peterhead.

And yet there was the one positive foray in the guise of Mission 50, which produced photography covering a large area of the USSR which included Kiyevka, Temirtau and Astakhov Skoye; and North Korea, including Yonpo Airfield, Hungnam and Hongwon.

As Mr Mackay said: “Mission 50 produced the highest number of camera frames from any of the 516 Genetrix [balloons]. All these targets were significant.

“Genetrix was successful and Scotland had played its part.

“Ultimately, Scotland was very important during the Cold War for both attack and defence. The radio spy stations were crucial in tracking Soviet subs and planes.”

Bubbleheads, SEALs and Wizards is available from Whittles Publishing at whittlespublishing.com/