Whatever disputes might rage elsewhere about climate change, the people who live on the piste and the apres-ski have no doubt of its impact.

Across Europe, there is a fragmented picture of many resorts struggling and companies being forced to adapt to a four-season strategy rather than rely on snow business alone.

Closer to home, the owners of The Lecht on the east side of the Cairngorms confirmed last week that they may have to cease operations due to a lack of the white stuff.

And, following what they described as a “dire” season, they have launched a crowdfunding appeal to raise £35,000, so that the centre can open for 2025.

But is this part of a wider malaise and are we witnessing the gradual disappearance of snow as the globe heats up? That, it seems, is still up for debate.

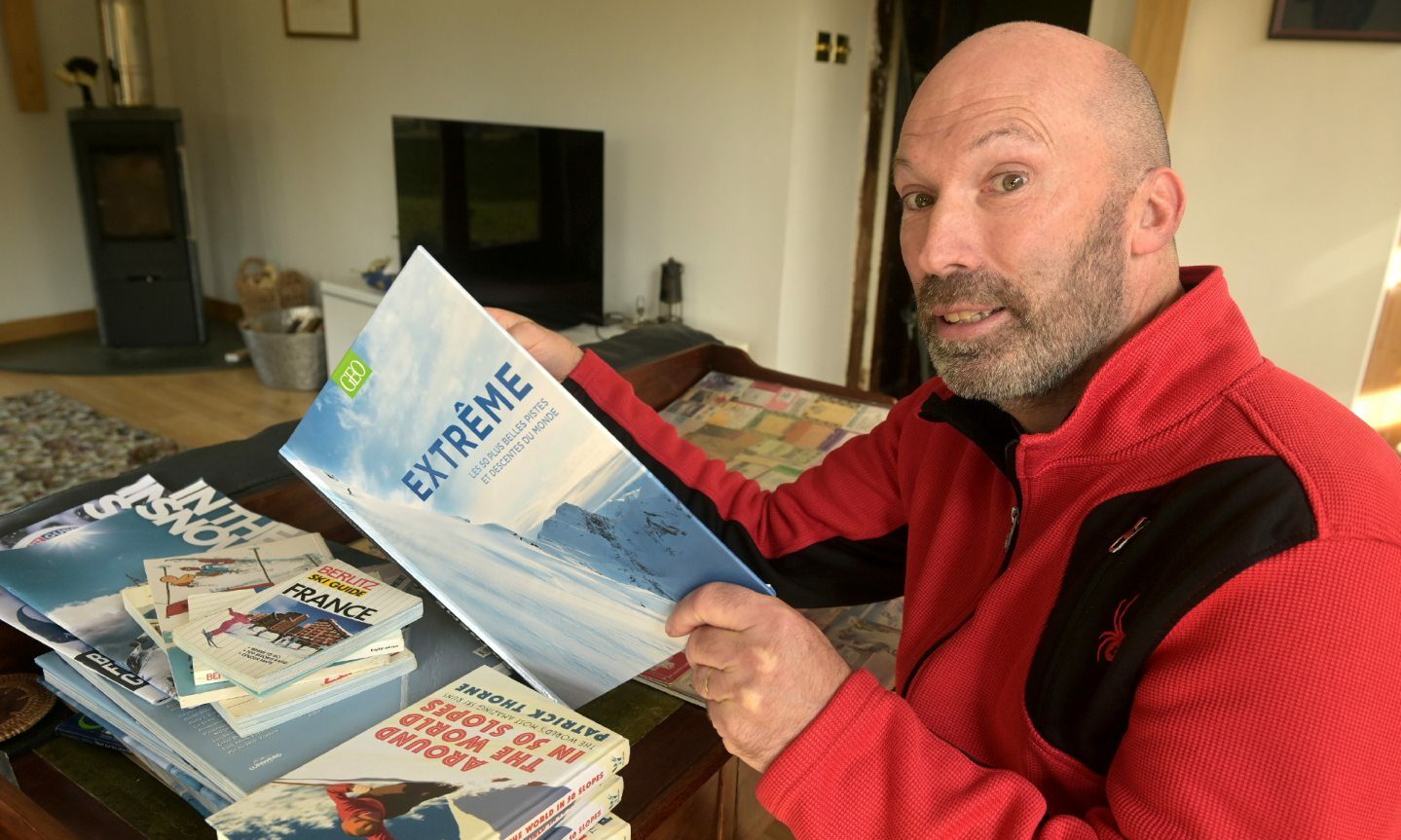

Patrick Thorne is one of the world’s leading writers about skiing from the comfort of his croft in Kiltarlity, near Inverness. Known as the “Snow Hunter”, he’s a best-selling author, a travel expert and the editor-in-chief of InTheSnow website and magazine.

Yet he appreciates the problems caused by an increasing lack of snow and voiced his fears that, sooner or later, it might vanish from the peaks altogether.

Are our ski centres running out of snow?

He told me: “I can’t see another outcome, the world is warming and we are just talking about maybe slowing it down a bit, but it’s still warming. We’d need to work out a way to stop it altogether and perhaps reverse things.

“When I first started writing about ski holidays in the 1980s, the news was always about ski area expansion and new slopes being created and environmentalists were regarded as interfering busybodies. Now, every press kit you get is full of green initiatives and many resorts employ environmentalists to ensure they’re doing all they can to cut CO2.

“I think we all desperately want good snow cover again in Scotland, but season after season now, it has become ever less predictable, so I think it’s about building a year-round business model, which the Scottish centres are well aware of and trying to do.

“They have also been helped a lot by their all-weather snowmaking systems.

Other countries are creating resorts

“In Saudi Arabia, which has more marginal snow conditions than Scotland, they are building a ski resort combining dry slopes with all-weather snowmaking machines, and investing their vast oil wealth in skiing.

“So it is physically possible to offer skiing in very marginal weather conditions, but whether we would want that kind of resort in the stunning beauty of the Highlands, even if the money were there, I’d say probably not!”

Not everything is shrouded in doom and gloom in the sector. After all, those involved in skiing, whether participating on the slopes, or balancing the books, are familiar with the vagaries of the Scottish climate and accept that some winters will be better than others.

That was certainly the response of Andy Meldrum, the managing Director at Glencoe Mountain Resort and the chairman of Ski Scotland when we talked last week.

We have had some ‘epic’ days

He said: “The challenge on the west coast this year was that it was much dryer

than normal and most of the precipitation fell on the east coast.

“That meant that we didn’t get the normal snow depths, but we still managed

to have 62 days of skiing with 9,677 skier days. Two season pass holders managed more than 50 days skiing. And, despite the low snowfall, we had some pretty epic days.

“We are used to good seasons/bad seasons/amazing seasons/dreadful seasons. The good news is that, with modern snowmaking [technology], we managed to maintain a sledging slope and basic beginners’ area from early December to mid April.

“We are continuing to invest in snowmaking and more equipment to better manage the snow. More snow fencing to capture the snow and more piste machines to move the snow around means that we are becoming more resilient in poor snow years.

Cold weather isn’t necessarily better

“Interestingly, in what was our biggest ever snow year in 2014, the average temperature on the west coast of Scotland during that winter was 1.5 degrees warmer than normal. The coldest winters are often too dry and don’t lead to good ski season.

“The difference between a good and bad season in Scotland can be the difference between a weather front being 20 miles too far south or too far north. So we’ve learned to take what comes and make the most of it.”

Iain Cameron, author of The Vanishing Ice, has logged how Scotland’s climate has changed since he was growing up in the 1980s. Frozen winters and long-lasting patches of snow were normal during that era, right through the following decade.

But then, at the dawn of the new millennium, he noticed things were changing. Fewer patches of snow survived from one year to the next and he turned into the Columbo of the Cairngorms, constantly returning with another query.

Most resorts can handle a bad season

He appreciates the consequences of environmental change are hard to pin down, but they will certainly transform the appearance of Scotland’s high places. But, in his opinion, the consequences needn’t be terminal for skiing aficionados.

He said: “I think there will be snow on Scotland’s hills for many years to come. The key question is will there be enough to make winter sports a viable option in 10 years’ time?

“We’ve seen ski infrastructure either being removed or mothballed in recent years and I expect that to continue. The odd poor season is something most centres can cope with, but when they come year after year, costs can’t get covered and something has to give.”

There’s another factor to consider, in terms of those who ski at an elite level. They’re resilient, resolutely down-to-earth characters capable of rolling with the punches.

Aviemore’s Lesley McKenna, for instance, who represented Team GB at three Winter Olympics is always prepared to cope with what life throws at her.

We make the most of things

As she said: “I was lucky to have grown up in a time during which the Highlands of Scotland could expect a fairly consistent amount of snow each winter.

“But things have changed drastically in the last 25 to 30 years and now the winter sports community in the Highlands are not alone in focusing their hope on the winter snow storms happening full stop – who cares if it’s windy or a whiteout?

“But it is a sobering realisation to contemplate the demise of snow in winter, at the ‘superficial’ level of less opportunity to go and have snowy adventures and, even more worrying, to contemplate this as part of wider climate breakdown.

‘A lot of potential for people to connect’

“In making that realisation, the wider connection between climate breakdown and the many challenges we face as humans today comes into the frame and finding ways to work around less than perfect situations, find novel solutions and support, specific local communities to be more resilient and collaborative seems like one way to be proactive.

“The Lecht supported snow experiences for 1500 kids this winter even under the awful conditions we had and it has more reliable open days than any other Scottish ski resort.

“That is a lot of potential for people to connect with each other, with Nature and experience how to really value and make the most of what is less than perfect.”

As you can see, she’s optimistic – even on a slippery slope.