Many of the soldiers were dead before they even escaped the water. Some of those in tanks were doomed from the moment they left their ships.

Others were caught up in the confusion, carnage and cacophany of clamour as the beaches of France were transformed into a sandstorm of battle 80 years ago.

This was D-Day, June 6 1944, which marked the start of the Allied invasion of Normandy, the greatest joint land, air and naval operation in global history.

Codenamed Operation Overlord, it was the start of a protracted offensive between Allied troops and their German counterparts towards the end of the Second World War.

Extensive training took place in Britain as thousands of troops prepared for the assault.

At the same time, an enormous build-up of vehicles, tanks, supplies and troops was orchestrated in the south of England and the 15th (Scottish) and 51st (Highland) Divisions were selected to take part in the offensive.

Conflict on a visceral scale

Many of these brave fellows never returned. But a few old warriors remain with their recollections of how D-Day was a giant lottery, with life or death often decided by tiny margins. Some came home to a hero’s welcome; others vanished into the ether.

The Allies implemented complex plans to keep the Germans guessing about where the invasion would take place and the location of the landings was a closely guarded secret. It was only once they had all left Dover that maps and final instructions were unsealed.

On the afternoon of June 5, the convoy set sail from the port, prior to passing down the Channel towards the Isle of Wight, then changing course en route to Normandy.

The codenames are now immortal

More than 5,000 ships and landing craft were utilised to transport more than 150,000 troops to the beaches on D-Day. As secrecy was still of the utmost importance, the landing sites were given codenames: Juno, Gold, Sword, Utah and Omaha.

Transport planes and gliders dropped large numbers of troops, vehicles, supplies and weapons in France. They seized coastal batteries, road crossings and bridges to aid the infantry advance into Normandy and slow down the German counter-attack.

Yet, once the campaign was launched, the casualties were still on a grievous scale.

At daybreak, on what was a grim morning, the advance towards the beaches started. 1st and 5th/7th Gordons landed on D-Day after the ‘western wall’ had been breached and the leading divisions started their move inland from the coast. The 5th/7th were the first battalion of the new Highland Division to set foot in France.

Jim Glennie from Turriff was only 18, but was among those who arrived on French soil, in the midst of a rapidly-accelerating casualty list. By the end of that first day, more than 4,000 Allied soldiers had been killed and most of them never stood a chance.

No time to think about the horror

The troops, who slept on the floor the entire time, had no idea what was waiting for them on the other side of the Channel. Jim, who is now the sole survivor from these Gordon Highlanders at 98, and signed up alongside his friend Ronnie McIntosh, did not know what day it was or even how deep the water would be when they landed.

He recalled: “I could swim, but Ronnie and another boy Norrie couldn’t, so I said I would help one of them to shore and then go back for the other.

“But when we landed, the water just came up to our knees.

“I put my foot on the sand and I looked down and, as the water came flooding into the craft, there was a dead body floating next to me. He must have been Canadian, because he was wearing a darker kind of khaki and he looked a lot older.

“But you weren’t allowed to stop. The sergeant told us: ‘Don’t stop, go straight on.’

You didn’t show you were scared

“We ran towards the field and someone shouted: ‘Hold it, mines’ – the place was covered in mines and we were ready to jump just over it. We then ran up this road, but I can’t really remember much about that, except the excitement.

“You were scared within yourself, but you didn’t show it. You just didn’t know what you were getting yourself in for – it was very dodgy.”

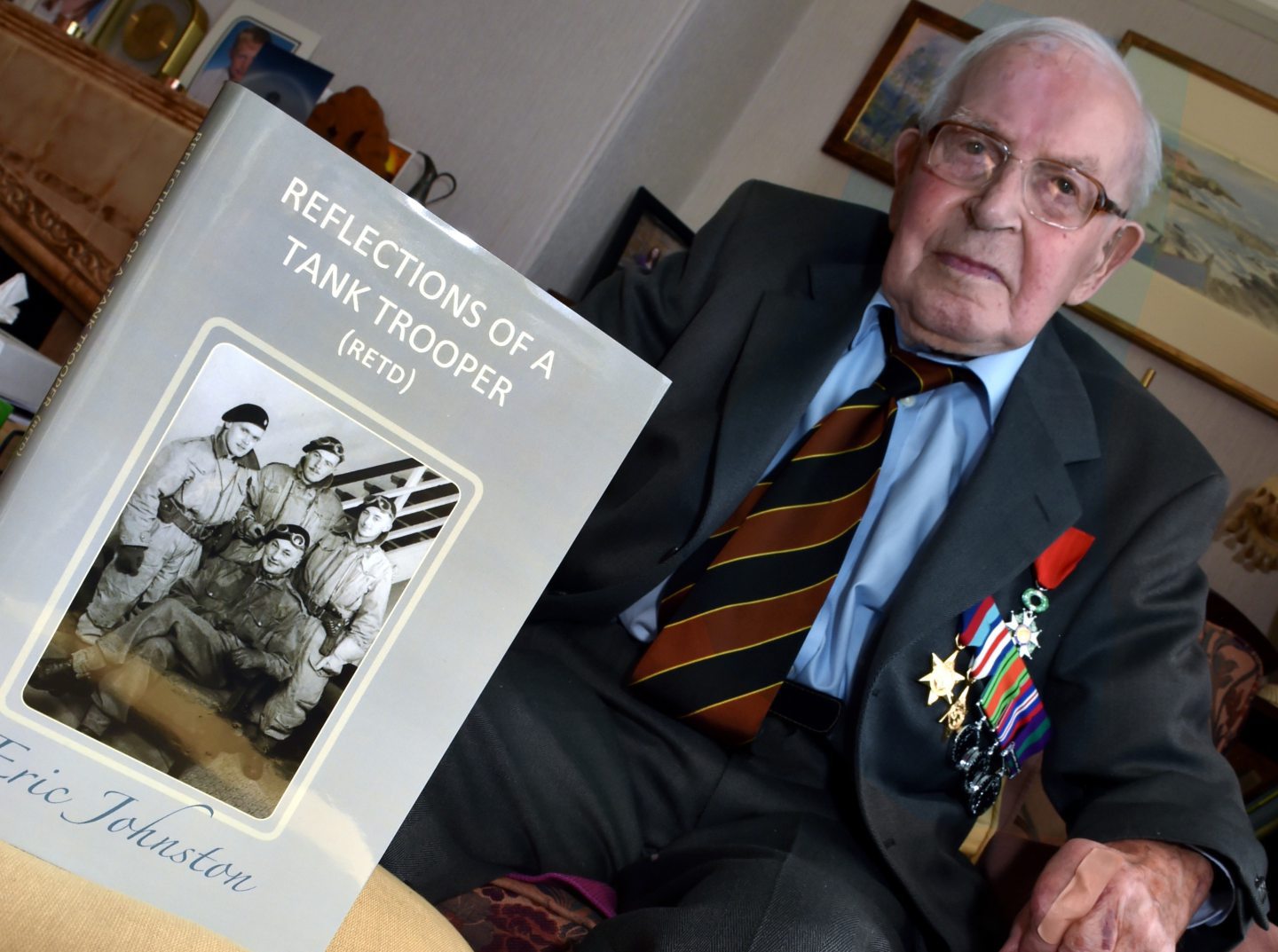

That was an understatement. Aberdeen tank trooper Eric Johnston, who died in 2020 at the age of 96, spoke about his outrage at the terrible scale of the casualties, particularly in the American ranks, and outlined how he and his British colleagues had benefited from being involved in meticulous planning in Moray.

It was terrible how so many perished

As he said: “We prepared properly in advance and it helped us, though it came at a cost.

“The result was that we managed to make successful landings on Gold Beach on June 6 with only five tanks lost in the process. However, on Omaha Beach, the Americans lost 27 of 32 tanks and there was no consultation with the military before launching.

“It was ridiculous and tragic – the tanks weighed 32 tonnes and they sank immediately after leaving the tank landing craft. All those poor fellows…”

Jim and his colleagues made some progress, but he and his company were ambushed by German soldiers while they were making their way towards Caen.

Several were killed or wounded, but Mr Glennie and some others managed to take temporary refuge in a roadside trench as Panzer armoured vehicles approached.

Gallantry was on display everywhere

He said: “The tank came past and was just spraying us, but we managed to keep our heads down. I remember thinking: ‘I don’t like this’ and I jumped out and ran up the road to try and get them when they came round a bend.

“So I’m standing there, firing my gun, and all of a sudden, I felt shots hit me in my right arm and the gun just dropped out of my hand.”

It was the end of his war, but after recovering in hospital, Jim was transferred by cattle train along with hundreds of others to Stalag IV-B, near Muhlberg in Germany.

His first day in the camp was his 19th birthday.

The campaign was successful

There was no quick victory for the Allies, but gradually, inexorably, albeit with occasional reverses, they seized the momentum and continued their onslaught.

Ruth Cox, the curator of the Gordon Highlanders Museum explained: “Special Forces teams and members of the Resistance made important contributions.

“They helped undermine German defences by carrying out acts of sabotage against transport, communication and power networks in the invasion area.

“In mid-July, Caen was finally liberated as part of Operation ‘Goodwood’. The 51st Highland Division held the line and successfully contributed to the operation.

“At the end of the month, the focus shifted west as American forces launched Operation ‘Cobra’. This offensive finally broke through the German line and spread out into open country, supported by further British attacks.

Paris was liberated in August

“During August, the 51st (Highland) Division had again been engaged without a break against a desperate and determined enemy who doggedly fought a rearguard action.

“However, on August 25, Paris was liberated. With the Germans in full retreat, the Allies now advanced rapidly on a broad front through north-east France.

“With the breakout of Normandy complete, the 51st Highland Division received orders from General Montgomery to return to St Valery, the site of the Division’s surrender and capture in 1940.

“And, on September 3, the fifth anniversary of the outbreak of war, the massed pipes and drums of the 51st (Highland) Division again played in St Valery. Many in the Division saw it as ‘repaying a debt from 1940.”

The real heroes never came home

Decades later, both Jim and Eric were awarded the Legion of Honour and the former will be involved in the opening of a D-Day80 exhibition at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen on Monday, June 3.

Yet they have never regarded themselves as heroes. As Eric told me when I met him at his home five years ago: “We were the lucky ones, who had the chance to live our lives and grow old with our families.

“An awful lot of boys never saw their loved ones again.”