Mirela Delibegovic’s life story reads like a Hollywood screenplay. As a teenager, she fled war-ravaged Bosnia by veil of darkness. Three decades later She’s been made Aberdeen University’s Regius Chair of Physiology – a role that can only be awarded by the King himself.

Lindsay Bruce spoke to mum-of-two Mirela, at home in Aberdeen, as she reflects on the journey that brought her to the Granite City, and to the attention of the King.

‘I wasn’t sure I’d ever go home again’

Alone at the Croatian border, two years into the bloody Bosnian war, 17-year-old Mirela Delibegovic faced the longest night of her life.

As Serb troops pointed guns at the convoy of trucks leaving the besieged country, Mirela’s driver turned back, at the crossing. With just one bag and a determination to reach Scotland, she decided to brave the perils of that cold, dark night alone.

“Everything in me wanted to return to my mother, but something inside me decided not to. I don’t know why because I knew it was dangerous. I was terrified… but I stayed where I was.”

The gravity of what she describes is not lost on me.

While I was watching the horrors of war unfold on Newsround, Mirela was living through it.

“I had a single entry visa to Croatia…” She pauses to grab a tissue.

“I wasn’t expecting to cry.

“The visa… that’s important… If I had turned back that night, I would never have made it to Scotland. I really didn’t know if I’d ever go back home.”

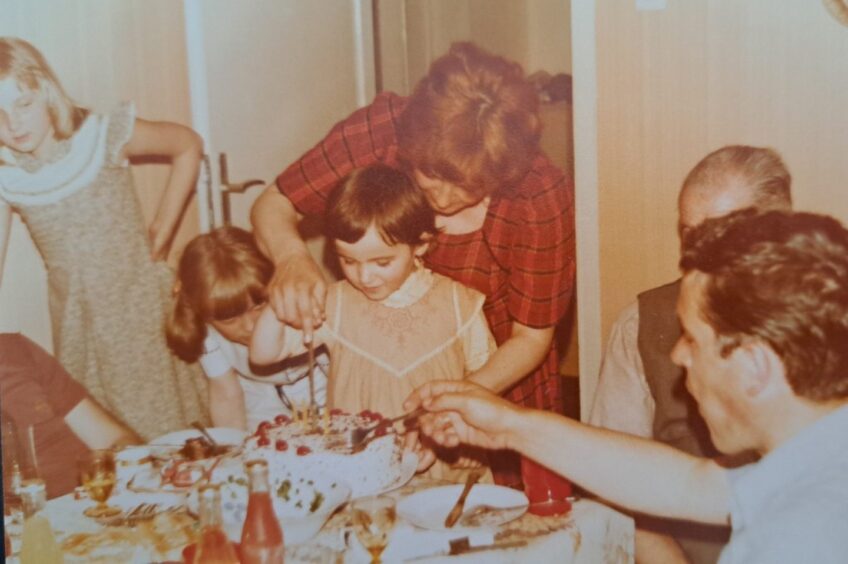

War became the everyday reality for teenage Mirela

That was August 1994.

Two years earlier at the dawn of the conflict, shortly after Bosnia declared its independence from Yugoslavia, her older sister left to take up her prize of a summer scholarship in Edinburgh. Mirela stayed with her mother in Tuzla.

As an officer in the civil territorial defence army, Mirela’s father was taken hostage. Just before her 15th birthday she learned he was still alive.

In February 1994, following a mortar attack into Sarajevo’s market place killing 68 people, a ceasefire was brokered.

“We had just sort of lived through the war until then. It became normal to kneel down in the basement where we lived until everything went quiet, then we’d go about our day as normal.

“Sirens sounding was a daily occurrence. Actually, hearing air-raid warnings in Ukraine, on the news, brought it all back… those moments in the bomb shelter.

“I remember one day my school was shelled. Thankfully no one was in the PE hall where a massive hole was left,” she explained. “I remember running down there to look at the damage.

“When the ceasefire was in place, all the young people finally felt safe to be out.”

‘I thought I was going to die,’ says Mirela

Peace was short-lived.

Out of nowhere, on March 10 1994, shells were once again dropped on to a civilian hotspot. This time in Tuzla.

“I was quite near a shop and glass broke behind us. I really thought I was going to die. The sound of the tank shell was like a rattling children’s toy.

“Communications went down so it took my sister days to get through to us. When contact was re-established she asked mum to let me go.

“That was the first time I think I believed in my heart that it was time to leave.”

From happy home to life in a war zone

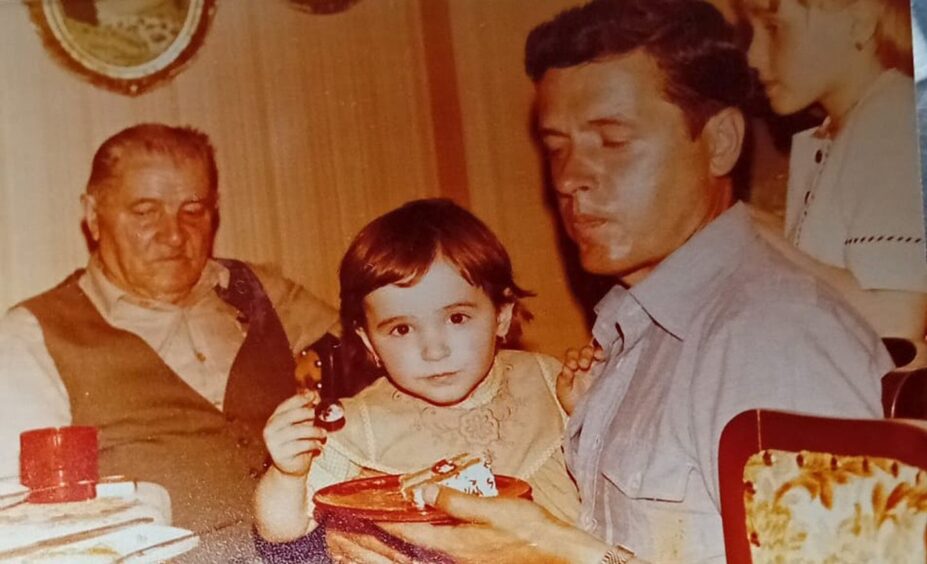

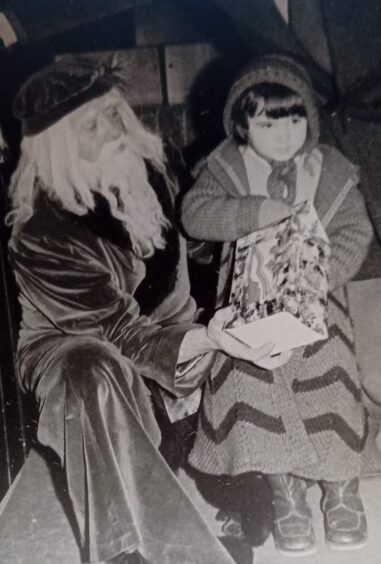

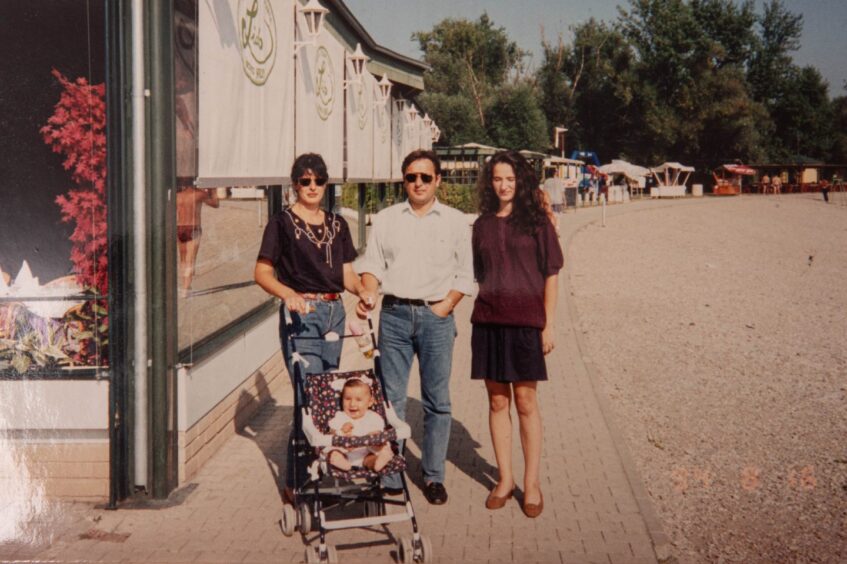

The grim reality was a stark contrast to Mirela’s idyllic childhood.

“It was lovely and normal. Very sheltered. I didn’t know much about anything. We went on holiday every summer to the Croatian coast. I played basketball in my city team. And you know, pre-1992, nobody knew what religion anybody was.

“You could tell by people’s names, but nobody really took notice. I was raised in a Muslim family. I never imagined that would be a problem.

“The first time I became properly aware of the war was when our residential primary school trip was cancelled. We were all so upset but no teacher would take the risk.

“The tensions seemed so far away. Until families started arriving in Tuzla [from other parts of Bosnia] with just the clothes on their backs.”

‘I could have gone back, but I stayed on my own’

Speaking from her west-end home, Mirela is currently juggling her university work with mum duties.

“My kids are 13 and 17. My son’s the same age I was when I travelled through the mountains to make it out on my own. I can’t imagine him facing anything like that.”

But that’s exactly what she did.

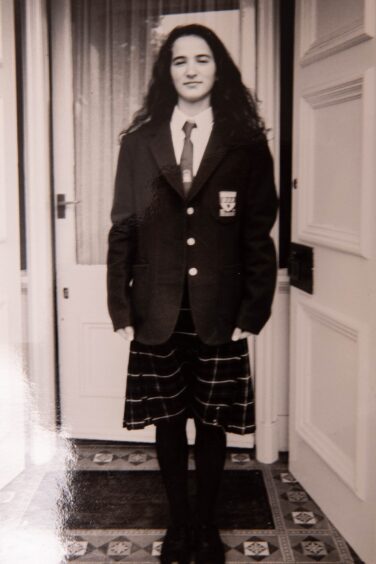

With aspirations to study medicine, and atrocities of war worsening, her mum reluctantly bid her farewell.

“My mother really didn’t want me to leave. She said I could only go if I got all As. I was a relaxed student, but when she made that promise I did what I had to. We study 15 subjects every year in Bosnia. I got all As.”

When her Croatian visa arrived Mirela’s parents organised a seat for her in a truck heading over the border.

“It’s a dangerous journey. Done in darkness. It was meant to take a night and a day to make it to free territory but because there were always Serb patrols and snipers on the hills, the trucks would drive with their lights off and stop frequently.

“We’d get to ravines and people would jump off because it felt so dangerous to cross makeshift bridges in trucks. My driver took a swig of Raki for courage.

“Eventually we got to the border but the couple I was with didn’t have a visa.

“They opted to go back, but I stayed on my own.”

‘Reaching Scotland was amazing to me,’ she says

Frightened, and emaciated from months of food shortages, she braved the night.

“It was terrifying. My mum hadn’t heard from me for days.

“During that night I was so alone. Surrounded by truckers. I’m grateful for the one lady who asked me to come and sit by her.”

Eventually, Mirela’s driver returned and she made it out of Bosnia to the British Embassy in Zagreb.

She flew to Heathrow where she met her sister. The pair took a train from King’s Cross to Edinburgh.

“She didn’t recognise me actually. I was so thin – only 52kgs by then.

“That journey… it was the most beautiful trip I had ever taken.

“As a teenager I was obsessed with Monty Python and Blackadder. Being in the UK was absolutely amazing to me.”

Mirela’s story could have been so different had she not fled

Mirela moved in with a family who steered her through her Highers.

“Even now I feel so lucky to be in Scotland. The people are so warm and welcoming. There were always people willing to help us.

“Yet the reality is without the war I would never have left Bosnia. I wouldn’t have left my home,” the 47-year-old mother-of-two reflects.

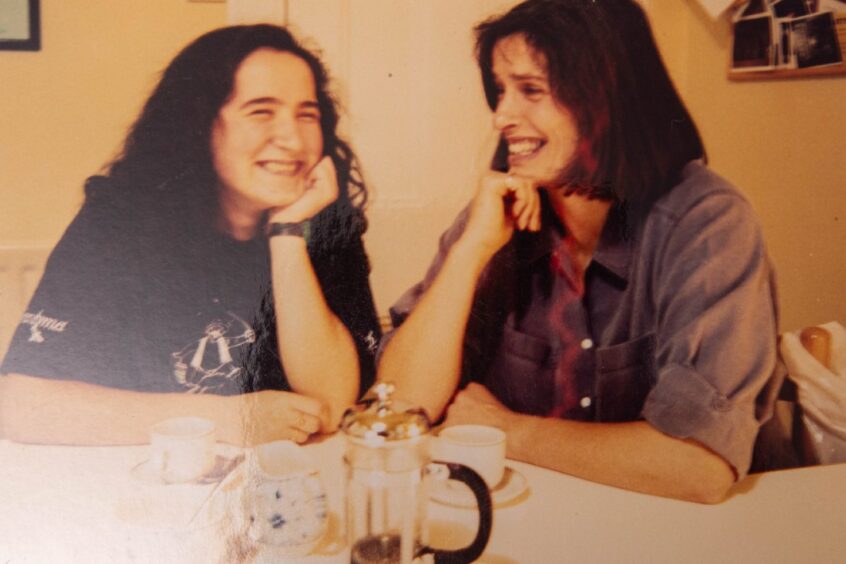

It’s a poignant moment. I look at Mirela as she speaks to me. She’s infectious; full of hope and energy. Her beautiful slavic lilt is betrayed only by the odd Scots – or maybe even Doric – pronunciation. She smiles continuously.

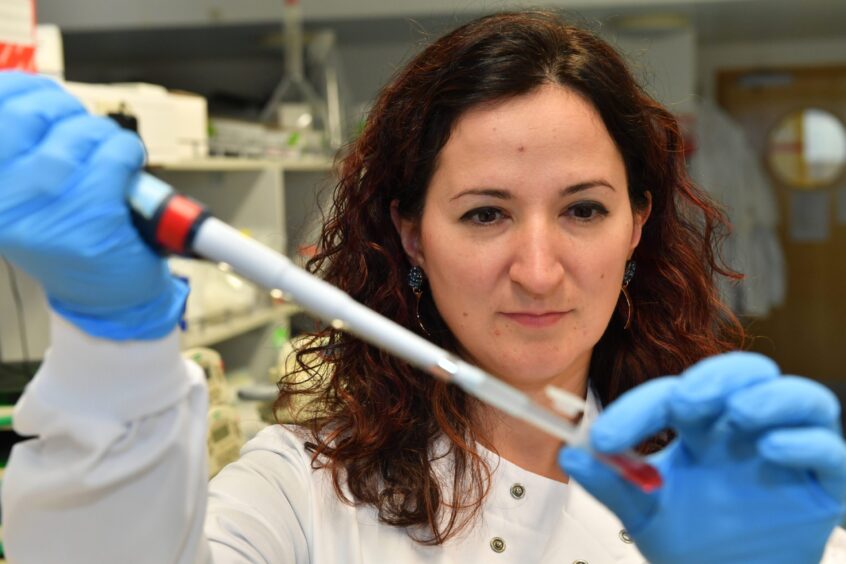

This woman, who fled war as a teenager, is the first Regius Chair appointed by His Majesty King Charles. And she’s currently the only holder of the title in all of the United Kingdom.

Her work at Aberdeen University, in the field of diabetes, is quite literally influencing the world and has the potential to change countless lives.

Had she stayed in Bosnia, or not been welcomed into this nation, I fear this reality could be so very different.

Edinburgh to Dundee, Dundee to Boston

“I felt so attached to Scotland that I stayed for university in Edinburgh.

“Although originally I planned to go home after the year in Edinburgh, but the night before my 18th birthday, again in a cease-fire, on the 25th of May 1995, the Serb army opened fire from tanks in Tuzla centre.

“They killed 71 people. The youngest was just two years old. 240 people were wounded.

“Fifty-one were all buried together together in the main park’s war cemetery under cover of darkness to avoid further shelling. When I eventually got to go home three years later, and whenever I go back, I visit and say a prayer there for those who died.

“It was at that point my mother said for the first time, that I should find a way to stay in UK.”

From Edinburgh University studying biomedical sciences Mirela moved on to a three-month project with Smith Kline Beecham in Harlow. Her passion for “everything diabetes” led her supervisor to suggest Dundee University – “one of the best places in Europe for diabetes research” as her next step.

Always interested in endocrinology, diabetes and heart disease, she was delighted to stay in Scotland.

“I was invited to give a talk in Dundee on my undergrad project and I got the place to do my PhD.

“I met my husband there too. He started his PhD at the same time,” she pauses to laugh. “Lots of us got married to each other, we were all so busy… we just worked all the time.”

The pair both completed their PhDs then did post-doctoral fellowships at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

‘We visited Aberdeen in the snow, and it was magical’

After the birth of their first child, they planned a return to the UK.

“We both work in the same field and it was time to start looking at faculty positions. Unusually Aberdeen offered two roles in the same place.

“I had never really been to Aberdeen – except for a concert – but the family I lived with in Edinburgh studied in Aberdeen in the 60s – so they offered to meet us to look around.

“It was February, 2007 I think. And it was snowing. We went to the Silver Darling. I looked out over the snowy harbour and it was just so magical.”

Professor Mirela became her university’s first female Regius Chair of Physiology in July last year.

The prestigious positions, now bestowed by the King, are in disciplines judged to be fundamental and for which there is a continuing and significant need.

“I’ve still got the Regius letter sitting there. It still feels really strange.

“But I don’t know, It just feels that sometimes if you’re in the right place at the right time, and you are surrounded by the right people, life takes you places.

“Like that night at the border. Those guys at the crossing told me to go back, but I stayed. That was the right thing.”

Mirela’s diabetes research could have global impact

Right now Mirela’s work is looking at the causes and consequences of diabetes, and the development of new diagnostic tests.

“The big hope,” she beams, “is whether we can tell if somebody’s at risk of developing type 1 diabetes before they present with symptoms, and before it’s too late. And if you could go to the pharmacy for that kind of test, like a lateral flow Covid test, rather than go to the NHS – which takes so long – it would be amazing.

“I’m also passionate about the connection between diabetes and heart disease.”

As she enthusiastically tells me about her work I’m stopped in my tracks by the figures.

“By 2030 there will be something like 765 million people worldwide living with diabetes. Even here it’s getting worse. Education is so important.”

And not just with regards to medicine.

Srebrenica massacre remembered three decades on

It’s 30 years this summer since the worst of the Bosnian war atrocities unfolded.

While people from various places in the nation were subject to genocidal murder and rape, it was the events of July 1995 in Srebrenica that became most synonymous with the full horrors of this war.

A town declared a safe zone by the United Nations, Srebrenica was supposed to be protected. But Bosnian Serb forces, led by General Ratko Mladić, took over the town and separated the men and boys from the women and children.

Over the next days, more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were killed, shot in mass executions, and buried in hidden graves. The women and girls were forced to leave, with many raped and forcibly impregnated.

UN peacekeepers failed to stop the massacre.

Later, the killings were officially recognised as genocide by international courts. Many leaders, including Ratko Mladić, were arrested and convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

‘Education is key, I’m grateful people knew about the war to help me’

Today – vast memorials and burial sites occupy Srebrenica – with more exhumations occurring with each new mass grave discovery.

Many mothers of Srebrenica still wait, and pray, for their lost husbands and sons.

“Yet deniers – of this and other genocides – persist,” Mirela says. It’s the first time she’s noticeably melancholic.

“It’s really appalling,” she goes on, “it’s recognised by law that it was genocide but you still have so many genocide deniers. I just don’t understand it. I cannot. It’s right in front of you. All the evidence is there but you know what we have to do, for our part, is talk about it; to educate.”

She tells me about Beyond Srebrenica, a Scottish-run charity educating school-age children about the Bosnian war.

“Every year there is a memorial day on July 11th commemorating what happened at Srebrenica. We’ve just had Holocaust Memorial Day too. And sadly genocides will continue… so the work of education is vital.”

Aberdeen hasn’t forgotten Bosnian atrocities

In recent years the charity – whose board members include Head of Robert Gordon’s College, Robin Macpherson – stage plays in Aberdeen schools, hold white armband commemoration days and there’s currently a national competition running for secondary school children.

“I’ll never understand how a human being can do something like this to another human being. Though it’s so interesting to me… I hear people say they’ve stopped watching the news because it’s full of horrible things.

“As soon as you do that you stop being interested in the lives of other people. It’s heart-breaking to watch, I know. But if we don’t see, we don’t learn, we get indoctrinated into all sorts of things.

“I’m grateful people understood and helped me.”

For what it’s worth, so are we.

Conversation