Butteries evoke strong emotions in people from the north-east, but have you ever wondered why?

Yes, they are undeniably delicious.

But what is it about these squished orbs of salted heaven that bring out those feelings of pride, loyalty and – when away from home – longing?

And if we are listing emotions, don’t forget anger. Many a heated argument has been had over whether they are called butteries, rowies or rolls.

These are all very deep questions that go far over the head of Me and My Buttery.

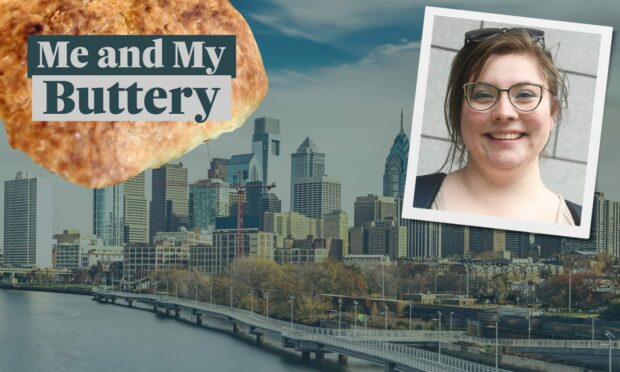

So to answer them we turned to Michelle Soto, an American who 10 months ago moved from Philadelphia to Aberdeen University to study for a PhD in folklore and ethnography.

Michelle spends her day researching the myths and stories different cultures tell about themselves.

And, ever since her Aberdonian boyfriend introduced her to butteries, she has been fascinated by how the delicacy shapes the way people in the north-east view themselves.

Lesson one from her boyfriend? They are not butteries, they’re rowies!

Hi, Michelle! Thanks for taking time out of your studies to speak to us.

You are very welcome, Me and My Buttery.

So when did you first come across the rowie vs buttery debate?

I’d listened to a podcast about it before coming over, but when I met my boyfriend, it was my first date I’d had with someone from Aberdeen. And it came up right away!

I arrived in Aberdeen calling them butteries, but now I get all of my rowies from the Byron Bakery [in Northfield], and I am committed to calling them that.

Why are the words we use for food so important?

What people call them is deeply rooted with who they are and their identity. When you choose a word and you attach part of yourself to it, you’re choosing how you want to be represented.

Hmmm, ok.

Humans like to tell stories, and it is through creating those names that we’re able to tell stories.

Also, the words I use tell the person I am talking to what my outlook is. A big part of folklore and ethnology is about connecting to a person’s truth as they want it to be known.

Wow, this is very deep for Me and My Buttery. Can you give me an example?

Right, well, I just took myself and my deeply Aberdonian boyfriend to the US to see my family in May.

And of all of the things we could have taken, what we took back was a dozen rowies.

It wasn’t shortbread. It wasn’t – well, you can’t take haggis into America, it’s illegal – but it wasn’t anything else.

And every morning, whichever family member we were staying with, we’d have rowies for breakfast.

We did not tell them that they are like 1,200 calories per rowie.

So why did bring rowies? Other than rowies are delicious, of course.

Well, for my boyfriend, the taste of a buttery is the taste of home.

It is a piece of food that is so specific to the place where my partner was born and raised. It’s a piece of his culture, it’s a piece of his identity.

He knows that the likelihood that all of my family members are ever going to come to Scotland is slim, so he wanted to bring something from him – from his home to my home to bring our cultures a little bit together.

But why do people get so angry about the rowie vs buttery debate?

I think a lot of it is just wanting to be proud of where you’re from. Because depending on which word you use, to some people, it’s telling you where you’re from and what you’re proud of.

If you say buttery, not rowie, it may kick up animosity because that’s a clear delineation. ‘Oh, you’re not from the same place as I am? Do you think I’m invalid?’

Will butteries feature in your PhD?

You know, I think they might. I am working on a dissertation right now about life stages and witchcraft in Aberdeen. I would imagine rowies will come up whether I want them to or not, because they’re such a quintessential piece of the culture here in the north-east of Scotland.

Fascinating. But I have to ask, Michelle: How do you eat your buttery?

How do I eat my rowie, you mean! Well, I eat my rowie warmed with butter and raspberry jam.