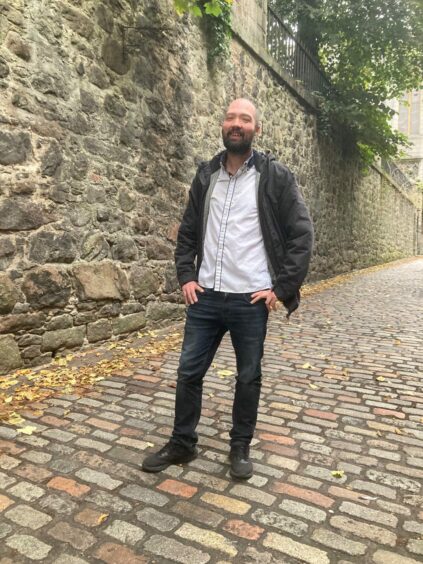

Andrew Robertson still likes a drink after work.

These days, though, the chef sticks to a self-imposed limit of two gin and tonics.

Any more and the staff at the Aberdeen bar he works at are under strict orders to cut him off.

“I’d probably get a telling off if I had any more,” he says with a laugh. “I’ve set myself a limit for a reason.”

Andrew’s attitude to booze sets him apart from many of his colleagues. In kitchens, hard drinking after work – and even during – can be the norm, he says.

But his attitude is borne of experience.

Since Andrew, 36, started out as a kitchen porter 22 years ago, the potent mix of alcohol, drugs and a career in the high-pressure world of professional cooking has twice brought him to the limits of despair, including an episode during lockdown where he almost took his own life.

As Sober October comes around, we continue our series that talks to people in the hospitality industry who have struggled with addictions.

For Andrew, telling his story is a chance to show the next generation of chefs that it is possible to work in kitchens and not give in to what he describes as the culture of drink and drugs.

It is also a reminder of the journey he has taken over the past two decades, and why he continues to work in a profession that almost killed him.

Mix of painkillers and alcohol ‘a recipe for disaster’ for Aberdeen chef

Andrew Robertson’s life can be split into two distinct periods – the time before “the attack” and what came after.

That pivot point came in November 2010 when he was hit by a car while walking down Ann Street in Aberdeen.

The driver of the car – a farm worker from Crimond – got out of the vehicle and beat Andrew to within an inch of his life. The beating was so bad that Andrew’s parents almost didn’t recognise him in hospital.

The assailant, who did not know Andrew, was eventually handed a five-year jail sentence.

But the legacy for Andrew was a catalogue of emotional and physical injuries, the pain of which he tried to drown in alcohol and painkillers.

“I was just trying to get numb, to feel human,” says Andrew, who went back to his kitchen job a few months after the attack. His drinking was made worse by the access he had to alcohol at the bar he worked at, where he got a staff discount of 50%.

“It was a recipe for disaster.”

Months of abuse went by. Then in 2011, fueled by a combination of whisky, vodka and painkillers after a shift at work, Andrew was fired for attacking a colleague.

He remembers the anger and rage he felt at the time, which turned to shame when his parents almost threw him out of the house for his actions.

The next day he vowed to get clean.

“When I saw the hurt I did to my folks, that was the tipping point,” he says.

‘You need a high to pick you up’

Since then, the Aberdeen chef has fought to remain free of his addictions.

Lockdown was an especially difficult time – as restaurants closed their doors, Andrew was placed on furlough and in the midst of a severe bout of depression came close to taking his own life.

Today he feels confident he has come out the other side. He hasn’t had a drink since April when the diagnosis of an inflamed pancreas put paid to even his G&Ts after work.

“I still like going out and having a good time but I drink tonic water these days and a Coke,” Andrew says. “I still get the same high from people and being happy.”

His concern now is his colleagues in the restaurant trade. His profession has brought him much joy and success.

But he is aware of the dangers kitchen life poses to people susceptible to addiction. He has seen many talented chefs leave the industry because of drink and drugs.

“You’ve got people that argue it’s part of the culture,” says Andrew. “But we need to change that. It’s wrong. It shouldn’t be like that. It should be like any other job.”

As Andrew sees it, there is no help in hospitality for people struggling with addiction. The industry, he says, attracts people that enjoy drinking to excess. These people find a like-minded community in the high-tension, hard-playing culinary world.

“When you do a great service, when that’s gone, you need a high to pick you up,” he explains. “You need something to keep you going. You go clubbing. The rush is gone, so you need to find it.”

‘Get smashed, do some stuff. It was normal’

Even before he was attacked in 2010, Andrew was a big drinker. He viewed long nights out with colleagues as all part of the job.

A drinker since the age of 14, Andrew found that he was able to prove himself when starting out by downing pints and shots and showing he was “one of the lads”.

He recalls one evening with a colleague when he knocked back a handful of Jaegerbombs, a double Jack Daniels and coke, a pint of lager and a vodka and coke in a matter of minutes.

“Going drinking every weekend, out till the next day after; that was the culture,” he says. “Get smashed, do some stuff. It was normal.”

It was a culture that extended into the kitchen. Andrew saw chefs abuse both alcohol and drugs while working. If they could still do their job, management would often turn a blind eye.

However, if you admitted taking drugs, you would get fired, This meant staff with addiction issues would keep them hidden.

“People are afraid to speak about it,” Andrew says. “People don’t know the signs.”

Hard-won advice for the next generation

These days, the Aberdeen chef feels strong enough to face the pressures of kitchen life without falling back into addiction.

He continues to work as a professional chef because it is a job he loves.

And he also knows that with his experiences he has something important to teach his colleagues.

“Be careful and don’t go overboard,” he says. “Have fun, enjoy it. But don’t turn something that is good into something bad.”

Conversation