Exhaustion, burnout and depression are all part of a mental health crisis that long predates the Covid pandemic.

Much has been said about the issues becoming even more pronounced during and in the aftermath of lockdown.

But have we had the answer to a calmer and more balanced life all along?

Stoicism, a philosophy founded in ancient Greece in the third century BC, is gaining followers across all walks of life – from world statesmen and business leaders to stressed parents and teens.

The Stoics held that nothing that happens to us is inherently good or bad, only our reactions.

The belief states that external things, such as health, wealth, pleasure, and material possessions are only good or bad insofar as they affect our character.

‘No point in getting angry’

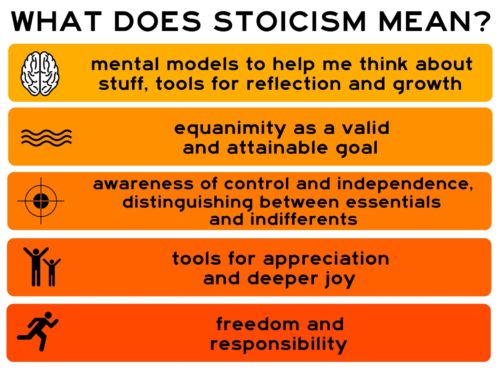

And underpinning it all is an ability to differentiate between things we can directly impact upon ourselves, and those things which are outwith our own control.

The latter are to be discarded from our thoughts entirely, freeing up our minds to focus on those things we can change or improve.

It also emphasises the futility of negative emotions such as anger, resentment and jealousy.

Much of today’s interest in stoicism revolves around three surprisingly easy-to-read core texts by the Roman Stoics Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, who were all active during the first two centuries AD.

Over the last few years, the internet has exploded with blogs, YouTube videos, courses and podcasts all devoted to Stoicism, most noticeably Ryan Holiday’s Daily Stoic e-mails, which go out to nearly half a million people every day.

John Sellars is a Reader in Philosophy at Royal Holloway, University of London, and author of the 2019 bestseller Lessons in Stoicism: What Ancient Philosophers Teach Us about How to Live.

Book’s popularity exploded in lockdown

The book has been translated into Korean, Greek, Russian, Polish, Spanish and Chinese among other languages, and he has found himself taking calls from journalists across the world intrigued by the interest in this part-philosophy, part-therapy.

As well as his teaching and research work, Mr Sellars is co-founder of two non-profit organizations aimed at bringing Stoicism to a wider audience, the Aurelius Foundation and Modern Stoicism, which hosts an annual Stoic Week and Stoicon for ever-increasing numbers.

Last year’s Stoic Week attracted 30,000 participants.

During the onset of the pandemic last year, the publisher Penguin reported sales of books by ancient Stoics going “through the roof”.

Before Covid, Modern Stoicism had 300 to 400 participants on its online courses.

After Covid, that changed to 3,000 to 4,000.

What’s causing this?

While Covid has accelerated the trend, Mr Sellars thinks the financial crash of 2008 was a pivotal moment.

He said: “Up until that point, there was this narrative that everything was getting better, everyone was consistently getting richer, in the UK house prices were going up, people were spending loads of money on credit on the assumption that everything would be fine in the future.

“There was a general level of optimism, there was that New Labour ‘things can only get better’ sort of thing.

“And then, suddenly, it all blew up in everyone’s faces.

“And I think, particularly with the younger generation who have grown up since that time, their rising concern over environmental problems, the idea that they might never be able to afford to buy a house, that they may never be as wealthy as their parents – which was the narrative throughout the 20th century, that kind of optimism has just gone.

Money ‘not the answer’

“So people are looking for something.

“Connected to that is the idea that not only might material prosperity not be so freely available, but also just might not be the answer either.

“And that there might in fact be more important things to focus on and think about in order to live a good life, as well as become a bit more resilient, in what to many people have felt like uncertain times.

“One of the lessons that stoicism can teach people is that while these might feel like unsettling and difficult times, they’re not – not from a broader historical perspective.”

So what is Stoicism?

“Stoicism is the view that the only thing you need in order to live a good, happy life is the right frame of mind, the right character.

“If you’ve got the right character, if you’re rational, if you’re calm, if you’ve got the right set of virtues, then you can live a happy life no matter what the circumstances you find yourself in and no matter what life throws at you.

“It enables you to be resilient no matter what the context.

“People connect with it, they find it genuinely helpful, both in difficult situations and in everyday life.

“I’ve met these people, I’ve spoken to them, there’s not an argument to be had about this, it’s an empirical fact.

“Stoicism encourages us to think about our thinking, to think about the value judgments we make about things.

“It encourages us to avoid making quick judgments and responses.

“That requires a kind of slowing down, so we can pay attention to how it is we are thinking about things.

“That injunction to slow down and pay attention, rather than just reacting hastily, I think offers an antidote to the increasingly fast pace of life, the 24/7 onslaught of information and all the anger on social media that makes people feel overwhelmed.”

Belief ‘offers answers’

Mr Sellars believes Stoicism is an alternative to the consumerist and materialistic nature of modern society.

“We live in a broadly secular, capitalist society where the only real value that you’re taught is ‘consume more and more because it’ll make you happy’.

“Stoicism offers an alternative to that.

“The idea that just buying more and more will make you happy is now being challenged in various ways, either because you’re not as prosperous as you’d hoped you would be or, with the environmental crisis, the idea that you’re consuming more and more might not actually be a good thing to be doing.”

An important element of thinking stoically is letting go of your own ego, realizing that you are but a small part of a much bigger picture.

Putting everyday stresses and disappointments into perspective is key to finding contentment, and being grateful for what we have.

Mr Sellars added: “Stoicism challenges egotism, that idea that you’re the centre of the world.

“These problems you have in front of you aren’t that significant in the bigger picture.

“There’s a strong streak of compassion in stoicism.

“It says that if other people are acting unpleasantly, it’s not because they’re morally vicious, it’s because they’ve got problems of their own, and what they need is actually some kind of help, rather than responding in kind with anger.

“That thought can be enormously helpful in defusing confrontations.”

Even more people discovered Stoicism with the onset of Covid.

The academic said: “I think there has been quite a bit of that kind of reflection over the past year, and Stoicism certainly chimes with that reflection on your values and what’s most important.

“And that material success and career advancement actually isn’t the thing that’s going to bring you lasting happiness and wellbeing, even if it’s something we need to deal with to make a living.”

Lockdown a ‘relatively brief period’

So how would the ancient Stoics handle lockdown?

“They would adopt the bigger view.

“It’s a relatively brief period within wider history.

“There are a lot of people who go to work, they come home, and at the weekend they go shopping and go to the pub – that’s what their life is.

“And suddenly they can’t do those things, and everything’s turned upside down.

“It’s removed all their routines and activities, and they don’t have anything to fall back on.

“So you can see why people in that situation think that the pandemic has destroyed everything. But realizing that those sorts of activities aren’t actually the be-all and end-all can make a big difference to people’s perspectives and indeed lives.”