Just one body donation can train hundreds of people – and save countless lives.

But out of thousands of potential donors, Simon Parson takes receipt of just 30 to 35 each year.

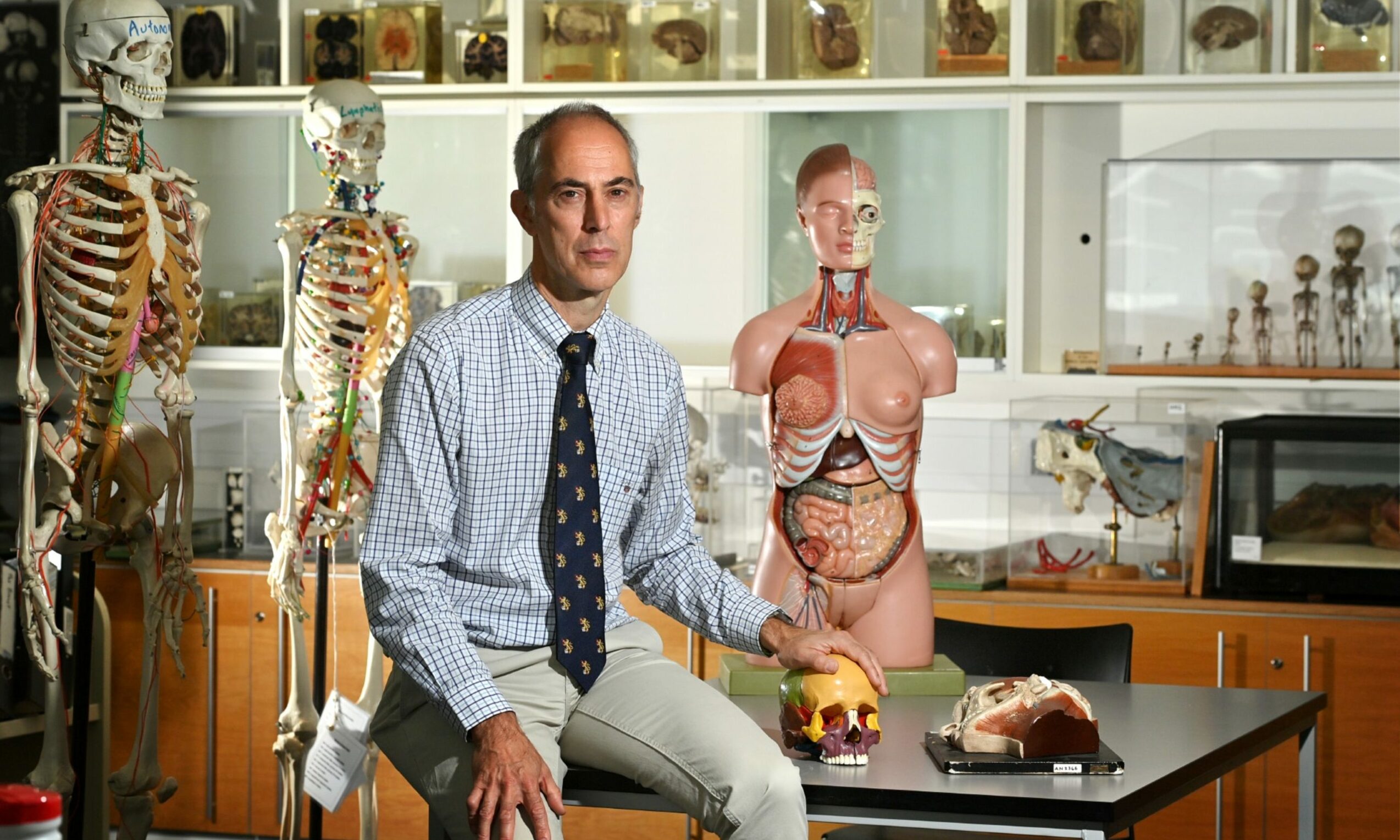

At Aberdeen University’s Suttie Centre, beside the city’s flagship hospital, he oversees the highly sensitive anatomy department.

His work helps scores of aspiring doctors every year, and provides essential support to qualified staff as well.

Prof Parson, the university’s regius chair of anatomy, has given us a behind-the-scenes look at the programme – providing proof, at least in some capacity, that there may in fact be life after death.

What happens when I die?

Around 2,000 people from across the north of Scotland have signed up to donate their bodies to the university – some having done so decades in advance.

When someone dies, Prof Parson and his team need to work quickly to communicate with the deceased’s loved ones, complete all the necessary paperwork and even organise travel so they can receive the body within 48 hours.

For many bereaved people, the phonecall to the anatomy department is the first they will make after learning of someone’s death – with staff specifically trained to handle each situation delicately.

And with donors spread throughout the region, including the western and northern isles, sometimes the next steps require ferry trips and multiple funeral directors.

When they arrive at the university, chemicals are added to the body to kill off bacteria, allowing it to be stored in a good condition for a lengthy period.

The law allows the university to keep the bodies for up to three years and, by that deadline, they must be cremated or buried.

It holds a special memorial each year for family members, with readings, music and first-year medical students also in attendance.

Prof Parson said: “It’s a very important day at the university, and we have people that come from really far away, like Australia and New Zealand.

“Unlike a funeral, they get a very long warning period before this, so they can arrange everything in advance.

“We put an awful lot of thought and care into the process – it’s absolutely not a case of ‘thank you for the donation, now it’s over to us’.”

How does teaching with bodies work?

A common misconception is that medical schools no longer teach using human bodies – instead preferring to show procedures on plastic models.

This was compounded when many universities were unable to accept donations at the height of the Covid pandemic.

And while Aberdeen does have a significant selection of highly-detailed and hand-finished models, it is not the only way students learn.

In years gone by, each group of eight to 10 would be assigned one body for all three years of their course, completing a full dissection during this period.

Now, however, each donor is anonymised – out of respect, to prevent any students working with a body they may recognise, and also to make teaching more efficient.

When Prof Parson is teaching a class on the heart, for example, he will likely have several organs on a table and students may see some chests with it still in place.

“Now, they might see 10 or 20 different people in one class,” he said.

“We have smaller numbers of students heavily involved in individual dissection and normally I tell them a little bit about the person – how old they were, the cause of death and other medical conditions.

“Generally they will come across those anyway – they’ll see something is missing, or they have a scar.

“So we will tell them a bit, but not so much so they might work out who it is – it’s a fine line.”

Huge scope of training

It is not just medical students who benefit when someone donates their body to the university, however.

Over the course of the three-year period, each donation could help train as many as 1,000 people each.

Around 250 students in each of the first three years will be taught anatomy in the department, as will dental students, physician associates – part-qualified doctors – and biomedical science classes.

The last group to benefit are those already qualified, who work with the department to practice specific procedures and operations.

“Historically, in terms of surgical training, they used to spend 24 hours a day in the hospital, helping with every operation,” Prof Parson explained.

“But now their time is restricted so it’s quite hard for them.

“We do a lot of training for reconstructive plastic surgery – not people who want to have a nose job, but who may have had large tumours taken out or amputations.”

Ability to help local surgeons

“We do quite a lot of that training because we have experts locally, and they can cover all parts of Scotland.

“Often the patient they come to needs something doing in the next five or 10 minutes or they’ll die – there’s no time for an ambulance or helicopter.

“There are a number of emergency procedures you can do on the roadside that are lifesaving, and we can train for that in our space.

“I find some of them the most satisfying because afterwards we’ll get an email saying ‘I had to do that a fortnight later, and if I hadn’t practised I would have been absolutely petrified’.

“The fact we can train paramedics on these procedures is fantastic.

“For someone like me, you often think it’ll be useful for them sometime later in life, but they could go and use it the next day.

“We get surgeons in too, who have to do operations that are so complicated they’ve never had the chance to do it before, typically very advanced cancers.

“It isn’t because they aren’t experienced, it’s because nobody has – they’re one-off.

“They can go into the hospital far more well-skilled than they might have been if we hadn’t given them this chance.

“That ability to help local people and improve surgeries and operations and health care in the really short time is something most people don’t understand.

“I think they think what we do is train medical students, and we do absolutely – eight-tenths of what we do is that – but there are all these other things.”

Moral obligation

While the process of receiving a body can sometimes be “a bit grim,” Prof Parson said every situation is approached with the utmost respect.

“It’s all done by trained, skilled and experienced people who can produce the best-quality parts we can,” he said.

“I try my best to find as many ways as possible to get as much out of everybody, and that’s certainly one thing I tell our students.

“It’s their responsibility to get as much of the experience as they can, as they only have it because of these very generous people.”

Alongside the moral obligation the students have to treat each body with care, there are strict legal mechanisms in place.

It means Prof Parson can potentially prosecute someone for failing to follow the rules, but this is something he has never had to do.

He added: “I’ve taught thousands of students and, if I think of how many I’ve had to have a really serious word with over my career, the answer is one.

“We have to poke them for not tidying up or arriving late, it’s small-grade stuff.

“Or sometimes I don’t like the way they’re dressed as I think they have to be respectful – shorts and flip-flops aren’t how you should come to anatomy, so I will send them home.

“But they do really understand their responsibilities.”

How can I help?

Due to the nature of the decision being taken, the anatomy team prefer to speak to people in person or over the phone before signing the papers.

And factoring in the immense time pressures after death, they strongly advise discussing the matter with your next-of-kin to ensure they are aware of your wishes.

While they cannot always accept every body, due to issues with illness, timing or logistics, often it can be donated to a different medical school in the country to ensure others can benefit from their generosity.

For more information, contact bequests administrator Agnieszka Kruk-Omenzetter by telephone on 01224 274320 or email at anat@abdn.ac.uk