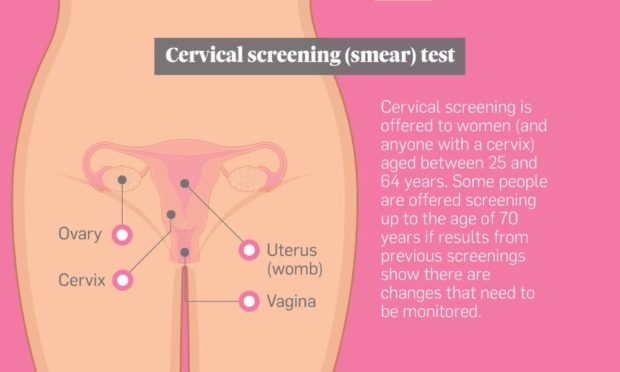

New leaps in HPV vaccination mean the days of going to the doctor for a smear test could soon be a thing of the past.

Researchers have found the “first ever concrete proof” that the school-age jab is dramatically cutting cervical cancer rates by almost 90%.

There are more than 200 types of HPV (human papillomavirus), all spread through intimate skin-to-skin contact, with 13 linked to a risk of cervical cancer.

And the new findings mean the way women are checked for signs of this could soon change, potentially with different age ranges or the introduction of self-testing at home.

Vaccine cuts cervical cancer rates by almost 90%

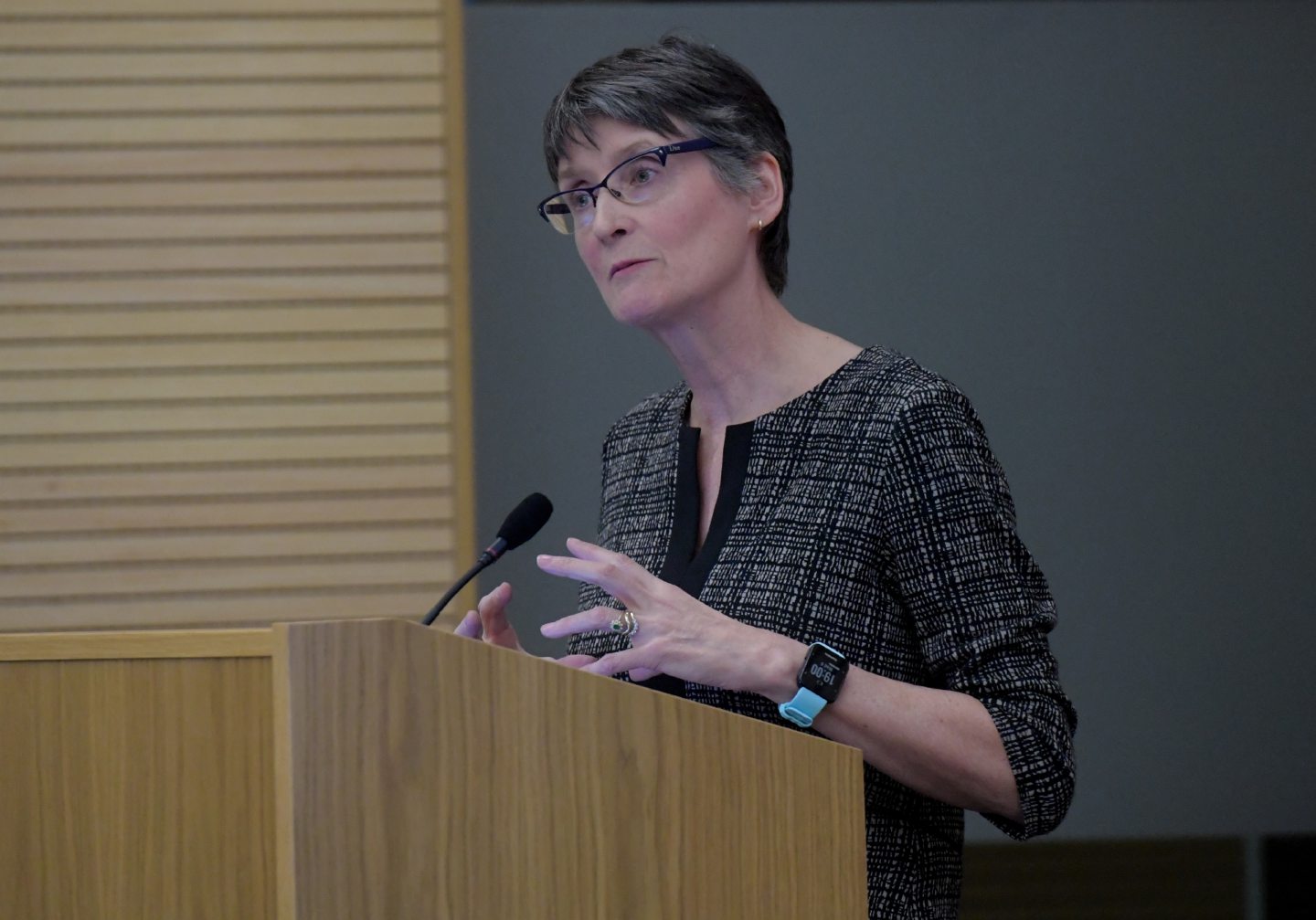

Aberdeen University gynaecology professor Maggie Cruickshank says the research could lead to “exciting” new developments in healthcare.

Published in medical journal the Lancet, it looked at what happened after the HPV vaccine was introduced to 12 and 13-year-old girls in England in 2008.

Those pupils are now adults in their 20s, the age range when most tend to pick up an HPV infection.

But the Cancer Research UK-funded study found their cervical cancer rate were 87% lower than their unvaccinated peers.

Cases for the age group, which are already rare, dropped from around 50 per year to just five.

Prof Cruickshank said: “The vaccine importantly protects against HPV 16; the one that’s most likely to cause cancer.

“What is really exciting about this paper is they’ve had a large enough study to show that it’s reducing the risk of actually getting cancers.”

Last week was a busy week. A study published in the Lancet journal showed the first ever concrete proof that the #HPV vaccine prevents #CervicalCancer and therefore saves lives.

That's something to shout about

Find more about the facts behind the headline👉https://t.co/6h8wj6uwbc pic.twitter.com/8j5TqhKHI8— Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust (@JoTrust) November 8, 2021

Younger generations have dodged a bullet

Prof Cruickshank says the English data backs up what we’ve already seen in Scotland where we’ve seen reduced HPV 16 and HPV 18 infections and fewer abnormal smears.

She has been working in HPV research since 1990 and said it was interesting to see the parallel of the quick development of the Covid-19 vaccine, with the actions after discovering HPV causes cancer.

“In Aberdeen, we were involved in one of the clinical trials where we were able to offer HPV vaccines as part of the clinical trial,” she said.

“It was great because we had so much interest from young women wanting to take part in that study.

“And then that evidence showed that it was an effective vaccine and a safe vaccine.

“Then the next thing it rolled out was a school-based programme.”

She said, as a mother of two daughters who have been vaccinated, that there’s relief in knowing her daughters have dodged that bullet.

The future of cervical screenings

Prof Cruickshank said the change in cervical screening to include HPV testing is a good move to the programme, and raised the possibility of fewer screenings for future generations of women.

“Because the girls who have been vaccinated are going to be at much lower risk, it means we’ll be able to change the screening programmes,” she explained.

“We will still be screening because [the vaccine] is not 100% protection, but it will mean that we will be able to do fewer screenings.

“To me, the great thing is that we will be looking at self-testing,” she said.

“So, women don’t have to go for a smear test, and that actually makes it much easier.

“If you can just take a test at home and send it off without having to get time off work or childcare, and get an appointment at the GP.”

In the future, it is possible cervical screenings won’t need to be start until a woman turns 30 or 35, and they won’t need to be tested as often.

Additionally, it won’t just be cervical cancers we’ll see less of, but also certain head and neck cancers.

“It’s good news all around,” Prof Cruickshank added

“And vaccinating all school children, since it’s gender-neutral, is going to give you that robustness to the system.”