Scotland made history when it became the first country in the world to set a minimum price for alcohol to help save lives.

Now organisations are calling for tougher action on the back of Ireland bringing in a similar law this month, which has seen some drinks more than double in price.

Ireland’s minimum unit price is 35% higher than in Scotland.

But is raising the price tag on alcohol really the answer?

Statistics show that the number of alcohol-related deaths have started to rise again in the last two years.

And experts have debated whether raising the cost of alcohol further is really the best way forward.

Impact of the pandemic

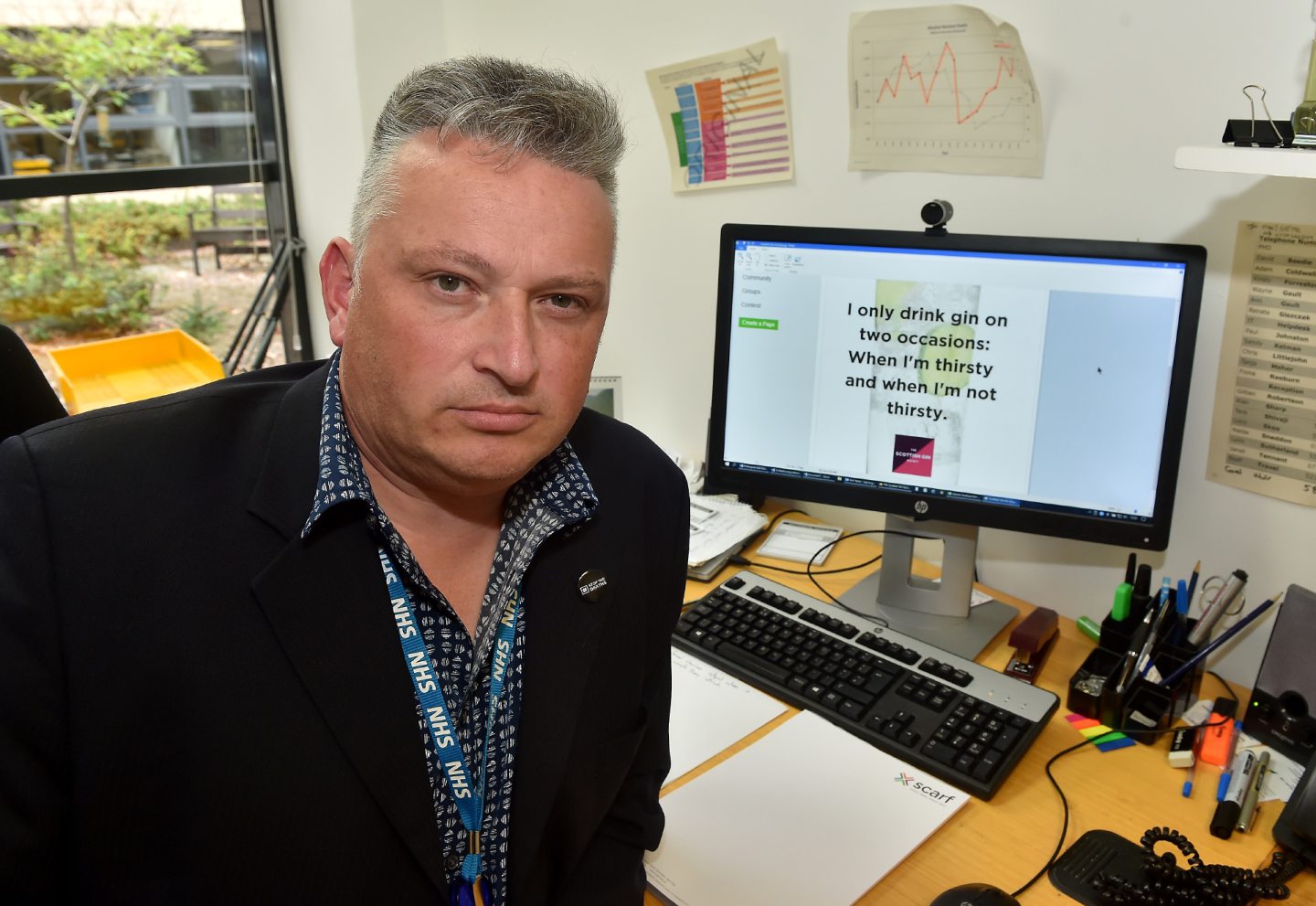

Wayne Gault, lead officer of Aberdeenshire Alcohol and Drugs Partnership says it’s difficult to know whether the MUP legislation has been effective since it was brought in four years ago.

“It’s clear when minimum unit pricing started in 2018 we saw an immediate response,” he said.

“We saw folk presenting to our local services concerned about alcohol issues at a higher rate than we’d seen before.

“When the pandemic kicked in at the beginning of 2020, that made a huge difference to people’s alcohol consumption rates.

“Whilst pubs were shut for a long time, people just bought booze from supermarkets and shops.”

Wayne is concerned about the rise in alcohol-related deaths and fears they will increase again over the next year.

He believes the minimum price in Scotland – which was set at 50p per unit – needs to be increased.

“The legislation went through parliament almost 10 years ago and then that was implemented in 2018,” he said.

“The unit price is still 50p her unit, but inflation has been rocketing and to have an equivalent impact it would really need to be 65 pence in today’s money.

“That would have the same impact.”

‘Alcohol is a horrific burden on the health service’

He highlighted how much harm alcohol has on the local community and NHS services.

“We know that liver disease is now the second leading cause of premature death in working-age people,” he said.

“Tackling harmful drinking has to be an essential part of the Covid recovery agenda. We can’t have behaviours established in Covid continuing.

“It’s not good for those individuals, for society as a whole and it’s a horrific burden on the already stretched to breaking point health service.”

‘Financial considerations are irrelevant’

It’s estimated that 51,000 children in Scotland live with a parent who has an alcohol problem.

Dr Piers Henriques, head of communications at Nacoa (the national association for children of alcoholics) also expressed his concerns.

He said: “We welcome the introduction of policy measures to reduce the harm of alcohol on children and families.

“However, for children of alcohol-dependent parents, we are concerned about dramatic increases in alcohol pricing because lack of money in the home is already an issue.

“We know from the helpline that financial considerations are often irrelevant when someone is addicted to drink.

“As well as reasonable interventions to moderate availability of alcohol, we need to increase the availability of support services for those addicted and their children.”

‘What we resist will persist’

However, Aberdeen-based psychotherapists Katarzyna Adamczyk and Zac Fine stressed that we need to think of other ways to combat the problem.

“People who struggle with alcohol abuse and misuse will continue to get the substance,” Katarzyna explained.

“Scotland has a binge drinking culture, and if we want to change that, we need to think more about long-term solutions.

“What people strongly dislike is when an authority is trying to impose change onto them against their will.

“People are autonomous creatures and want to be treated as such. Hence, if we impose something onto others, they will resist it and what we resist will persist.”

She believes there needs to be a change in how we think about alcohol in order to tackle addiction.

“There is a need for more education regarding alcohol and its deleterious effect on our mental and physical well-being,” she said.

“Rarely do you hear people speaking about alcohol as one of the most toxic depressants available to us.

“And this could be a key message that each one of us should be considering before buying and consuming alcohol. If you know better, you do better.”

‘Trauma to the next generation’

And Zac believes raising the price of alcohol again will take away even more freedoms from already hard-pressed groups – those on lower incomes.

He questions why no-one appears to be investigating the reasons why someone might “drink themselves to death” with 16.7% more alcohol-related deaths in 2020, than in 2019.

“If you deprive low-income people of affordable alcohol, you lower the quality of life for many, and for those who are alcoholics you may create acute distress,” he said.

“It’s far better to find a collaborative way of working with them to heal.

“This could be something with a social element such as group therapy, time in nature or gardening groups.

“That way we don’t need to pass on all this trauma to the next generation.”

‘Alcohol intertwined with financial problems’

Andrew Misel, director of Alcohol Change UK, says there’s often a link between alcohol and financial difficulties.

“Problems with alcohol are often intertwined with financial problems,” he said.

“Someone’s drinking may get worse because they have money worries, and heavy drinking may leave someone short of money for other things.”

He admitted there’s “always a risk” that increasing alcohol prices could lead to some people spending more money on the substance.

However, he stressed this isn’t the case for everyone deemed a heavy drinker.

“We need to be wary of talking and thinking about heavy drinkers as addicts who will do whatever it takes to get alcohol,” he said.

“Most people with alcohol problems consume varying amounts of alcohol over time and want to move on from the chaos and build a happier family life.”

Minimum unit pricing targets the strongest, cheapest alcohol on sale, but he stressed that there needs to be other targeted measures to tackle alcohol harm.

He suggests we need to improve the labels on alcohol so consumers know exactly what’s in each bottle as well as more funding for alcohol treatment services.

‘Final report due in 2023’

Twenty-eight organisations have called on the Scottish Government to increase the minimum unit price in an effort to save more lives.

Leading health and children’s charities have written to Public Health Minister, Maree Todd MSP, recommending it is increased from 50 pence per unit to 65p.

Responding to the calls, Ms Todd said: “We are absolutely committed to ensuring we have in place a level of minimum unit price that remains effective in reducing alcohol harms.

“When we announced we would review the level of minimum unit price after it had been in place for two years, we did not know we would also need to factor in the impact of a pandemic and a changed legal landscape post-Brexit.

“Prior to the pandemic, we were seeing early encouraging signs of a reduction in alcohol sales and a reduction in alcohol-specific deaths.

“The evaluation is ongoing, with a final report from Public Health Scotland due in 2023.

“The pandemic and the changed legal landscape post-Brexit are two significant events that are impacting on this work and must be factored into the analysis.

“It is important this work is carried out thoroughly as we must ensure any change to the level has a robust evidence base.”

Read more:

Scotland’s alcohol death rate highest in UK

Recovering alcoholic plans north-east’s first alcohol-free nightclub