David Jones woke up with a splitting headache after a night of drinking. “It must be a hangover,” he presumed.

At 38, he’d not long moved from the north-east to Amsterdam for a new role with energy giant Shell.

He didn’t think it could be anything untoward – company medics had given him a clean bill of health before he flew over.

But as he opened his eyes and stretched over to answer his ringing phone, he realised something was very wrong.

“I couldn’t talk,” David recalled. “Not a word.”

Full of panic, he made his way to see some friends who rushed him to hospital.

“Within minutes” of stepping through the door, he was in the intensive care ward.

He’d spend the next fortnight there, unable to speak or even swallow unaided.

The doctors had no idea what was wrong, but knew it was serious.

It took two weeks of tests before they were able to give David an explanation.

“They found out I had a stroke,” he recalled. “Normally it is on one side of the brain and affects half your body.

“I had two at the same time – they’d never seen it before, so I understand them being confused.”

Stroke effects left David ’embarrassed’

After a couple of months, David headed back home to Aberdeen and started speech therapy.

He also made a gradual return to work, but found his life had become very different.

“After six months I was full-time, but I relied heavily on emails and text,” he said.

“Telephones were impossible – and meetings were almost impossible too.”

His condition had also knocked his confidence significantly.

“When I was in the hospital it wasn’t too bad – there were doctors and nurses to look after me.

“But when I found myself at home, my friends didn’t know how to react to me and I didn’t know how to react to them. I found that very scary.

“I’d always been outgoing and confident but every time I was in the supermarket and I saw a colleague I turned around, I didn’t want to meet them.

“I wasn’t frightened, but I felt embarrassed about my inability to talk.”

Lightbulb moment that changed David’s life

David, now 76, is involved in a number of different support groups around the north-east.

And he’s found, for many people, the psychological side of stroke recovery is far more debilitating than the physical effects.

But one day he had an epiphany that changed how he saw his situation.

“I realised it’s not my problem that I can’t talk,” he recalled. “It’s his that he can’t understand me.

“That was a big moment in my recovery.

“People who’ve had a stroke need to realise it’s not their problem, it’s everybody else’s.”

David added: “At times if I’m in a shop and I say something, they might not understand and ask me to write it down.

“Initially I did that – but now I tell them to listen to me.

“People hear my speech and think I’m drunk or stupid – or both.

“I’ve been turned away from pubs when I’m stone-cold sober.”

‘Life isn’t normal – but it’s near enough’

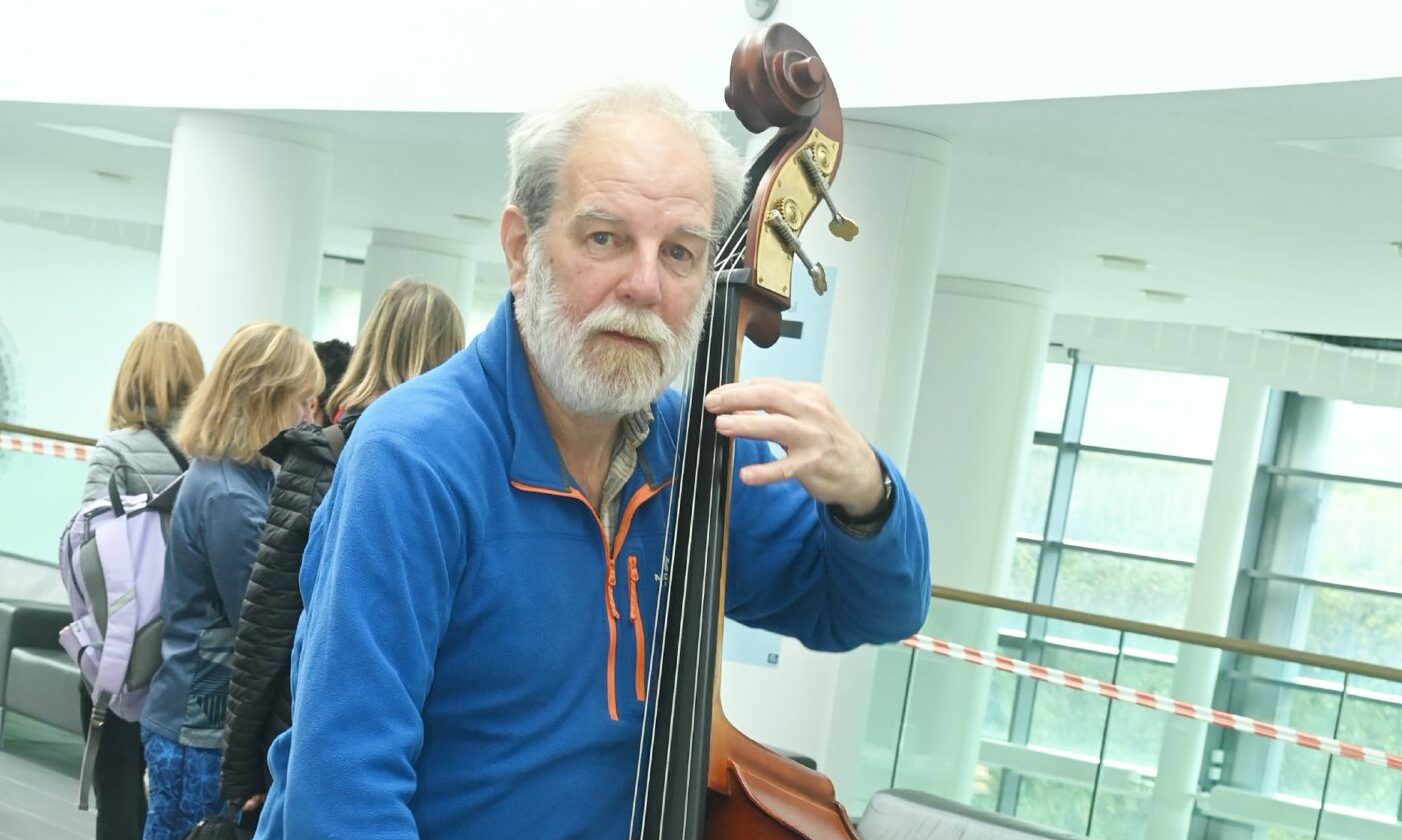

Prior to his stroke, David’s main hobby was music, playing the trumpet and piano.

But the paralysis of part of his face and “dodgy” left hand meant he had to give those up.

He’s since found a new passion with the double bass and plays in two bands – one Scottish and one classical – and advocates for others trying out music therapy.

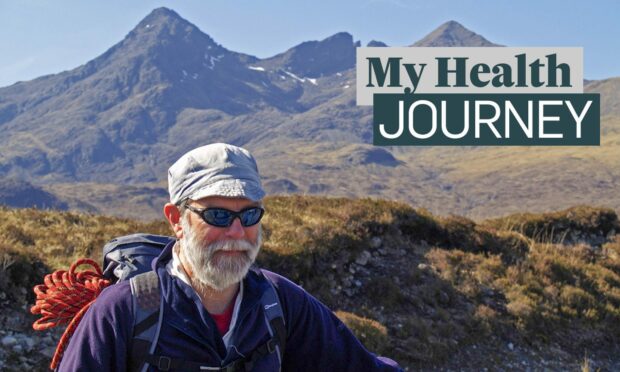

David is also the chairman and founder of Walk-Ability, which helps people of all abilities enjoy the great outdoors, and works with the Stroke Association.

“I would say my life now is obviously not normal – but it’s near enough,” he explained.

“Disabled people are generally very innovative and can adapt to the situations they find themselves in.

“It’s not always easy to find support but it is out there, and it’s well worthwhile.”

Conversation