Edward Mountain MSP spent 12 years in the army. But nothing he faced as a soldier frightened him as much as bowel cancer.

The 62-year-old Conservative, who represents the Highlands and Islands in the Scottish Parliament, fought a months-long battle with the disease, even as he contested crucial elections and campaigned door-to-door.

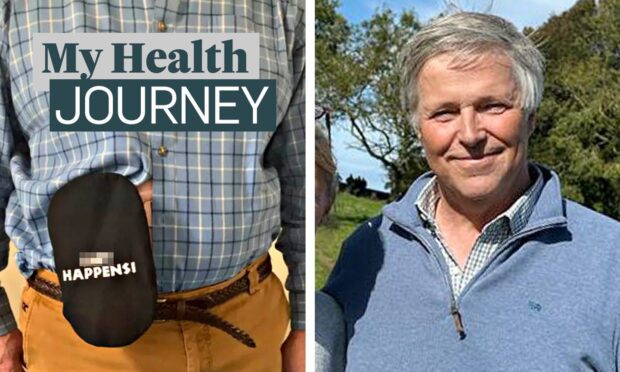

He wore a stoma bag — the pouch worn on the outside of the body that collects bodily waste — in Holyrood.

And though he faced the disease with humour — one of his stoma bags bore the phrase ‘Shit Happens’ — he still vividly recalls the fear of that time, when for the first time in his life he felt vulnerable.

“I had some interesting times when I was in the army,” he says.

“But I didn’t feel as vulnerable in the army as I did with this.”

A terrifying diagnosis and a rewriting of a will

The day Edward’s life changed, he was busy preparing for a party.

It was the end of June in 2021, the day of Holyrood’s annual staff summer barbeque. Edward had already been in for tests after finding blood in his poo a few months before.

He’d also had a colonoscopy, the procedure that tests the inside of the bowels to determine what might be wrong.

But none of that was on his mind that June morning when his phone rang in his office. Edward answered it and was told he had bowel cancer.

“I remember sitting in this chair just thinking, Oh, shit,” says Edward, speaking from the same office. “I just said to everyone I’m going for a walk and I went some of the way up Arthur’s Seat and then came back.”

What did Edward think about on his walk up the Edinburgh landmark?

“That I’m going to die,” he says.

“I was told on the phone that a surgeon would be in touch with me in 10 days, and not to worry, that it would be all fine.

“But you can’t communicate that on a telephone. I can’t see what you’re really thinking. So yeah, I was convinced I was going to die.

“The first thing I did when I got home was dust off my will, rewrote it and then waited for the call from the oncologist.”

Starting chemotherapy and ‘eating a frog’

Doctors soon reassured Edward his cancer was treatable. Caught early enough, the survival rate for bowel cancer is about nine in ten.

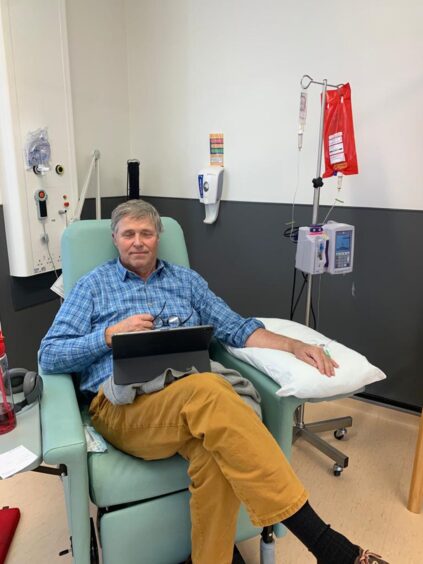

Treatment, however, meant radio and chemotherapy, the latter of which he would soon learn to hate.

How much is difficult to gauge — Edward admits he has to be careful when talking about his treatment because the last thing he wants is to dissuade anyone from doing it.

As he puts it, “the other option wasn’t great either”.

But his description of his multiple rounds of oral chemo (the radiotherapy, in comparison, was “a walk in the park”, he says) is vivid enough.

“Taking the pills, of which there were I think six in the morning and eight at night… yeah, I came to hate them with a vengeance.

“You can drink Ribena or Irn Bru or whatever to keep them down but I still struggled.”

To cope, Edward relied on something his dad used to tell him.

“If you’re going to have to swallow a frog, don’t spend too long looking at it,” he says. “When it came to the pills, it was the same.”

The treatment didn’t stop him from working, though. He took the afternoon off on chemo days because, he says, “I couldn’t really function after that”.

But he found that the hustle of work – he was party whip at the time and also still working with constituents – kept his mind of his cancer, most of the time, at least.

“Work was hugely therapeutic,” he says.

“Though there were a couple of occasions when I was dealing with issues relating to bowel cancer, and the lack of help people thought they were getting. I found that really, really difficult.”

Why having bowel cancer is like being in the movie Alien

The next stage of treatment was surgery to remove part of his bowel. Edward describes himself as a staunch defender of the NHS. Nevertheless, he freely admits he went private for the operation, which was eventually done in London.

“No one should have to do that,” Edward says of opting to use private health care, before explaining his reasoning for doing just that.

Mostly it was because of repeated delays, he says, and specifically a letter from NHS Grampian that left the scheduling of his expected surgery in doubt.

“Have you seen the film Alien?” Edward asks. “That’s the best analogy I can give.

“You think you’ve got an alien inside you and you want to get it out as quickly as possible. It’s something that’s deeply horrific and you don’t fully understand it, your body’s let you down, get rid of this goddamn thing.

“So to be told there’s going to be a delay, that just didn’t do it for me. People will criticize me for going private. I don’t, because it freed up the space for somebody else. And it meant I got my treatment.”

Learning to live with a stoma bag

Another reason Edward went private is because his NHS doctors told him that if he got the operation in Aberdeen he may have his stoma bag for up to six to eight months.

He admits he hadn’t given much thought about the need for a stoma in the run up to surgery. The operation was his main focus, not the need for a bag to retain a portion of his colon on the outside of his body.

“It was the least of my worries,” he says.

Even in the days after the operation, hospital staff took care of the stoma bag as Edward recovered. However, around day three, he had to change it himself.

His first attempt did not go smoothly.

“I’m tottering across to the loo and the bloody thing dropped off,” he says. “That’s when I decided that I’d better learn how this works.”

Pain, seepage and the thought of being blown to France

He eventually got the hang of bag changes — usually every two days — though he says the stoma “wasn’t an easy thing to get used to”.

His wife Charlotte was able to help him, and he says he can’t imagine how anyone does it on their own.

Still, it wasn’t easy.

“I had quite a lot of seepage, and you’ve got a lot of pain around it, but we got around that,” he says.

“It was when you had to empty bags in public. I remember having to do it in a disabled loo in a service station and there was no shelf.

“The toilet wasn’t that immaculate, and you’re laying out your scissors and your wet wipes and your mirror and your bag on the floor – it’s just not that great.

“Also, I’ll be honest with you, I like a beer occasionally, and I was terrified that this thing was going to blow up like a hot air balloon and I was going to drift off to France.”

Taking a stand on stoma bags and cancer test sensitivity

Edward eventually had his stoma reversed, though not before wearing his ‘Shit Happens’ one to Holyrood (“My daughter bought that one for me,” he says, laughing).

Today, he talks openly about his experience to help destigmatise stoma bags. But he makes it clear that people who use stoma bags are able to live full lives. It’s just sometimes they need a little help.

“There’s 20,000 people in Scotland that have a stoma bag,” he says. “They might need facilities, they might need the loos sorted, but they are perfectly normal human beings. They can do most of it.”

Edward is also using his platform as a politician to call for improved bowel cancer screenings. He praises Scotland’s current home-testing kits that are sent out every two years to everyone between the age of 50 to 74.

However, he says the sensitivity of the tests are currently set at 80, which means it can detect 80 micrograms of haemoglobin per gram of faeces. Edward believes the tests should be able to detect down to 20 micrograms.

“If you get it down to 20, it will pick up all bowel cancers,” he says. “It will mean a few people get picked up that just have polyps or other things. But a few more colonoscopies are a lot cheaper than radiotherapy, chemotherapy and then an operation.”

It’s not just money that Edward is thinking about. There is his own experience of treatment.

“It’s brutal,” he says. “If I can avoid anyone going through it, then of course, I’m going to do that.”