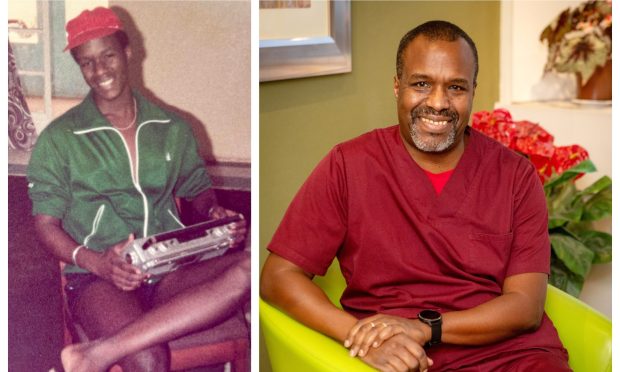

He arrived in Aberdeen almost 40 years ago, a fresh-faced — and freezing — medical student from the beaches of The Gambia.

Today, he is a freshly-minted OBE, recognised in last month’s new year honours list for his work as a leading prostate surgeon, the founder of a pioneering cancer charity and building a maternity hospital in Africa.

But can I get Professor James N’Dow to talk about his royal recognition? Fat chance.

“Of course I’m honoured,” he says with a big laugh as he sits in his office at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. “I mean, my parents were big royalists so they, God bless their souls, would have been tickled pink.”

James, though, is less tickled, which is a shame considering the OBE is the reason I’m here to interview him.

But luckily for me, James is funny, charming and full of enough stories for a dozen interviews. A humble reluctance to discuss his award is no inconvenience.

And of course, the OBE is really just an excuse to hear James’ story, which by any standard is a peach. How’s this for a narrative arc?

A young West African man drifting through life who thanks to a mysterious phone call finds purpose — and love — in a country that though much colder than the one he left eventually melts his heart.

Forget the OBE, this is the real story. Plus — and happily for me — it’s a subject on which James has plenty to say.

Especially the bits about the cold.

The mystery phone call that takes James to Aberdeen

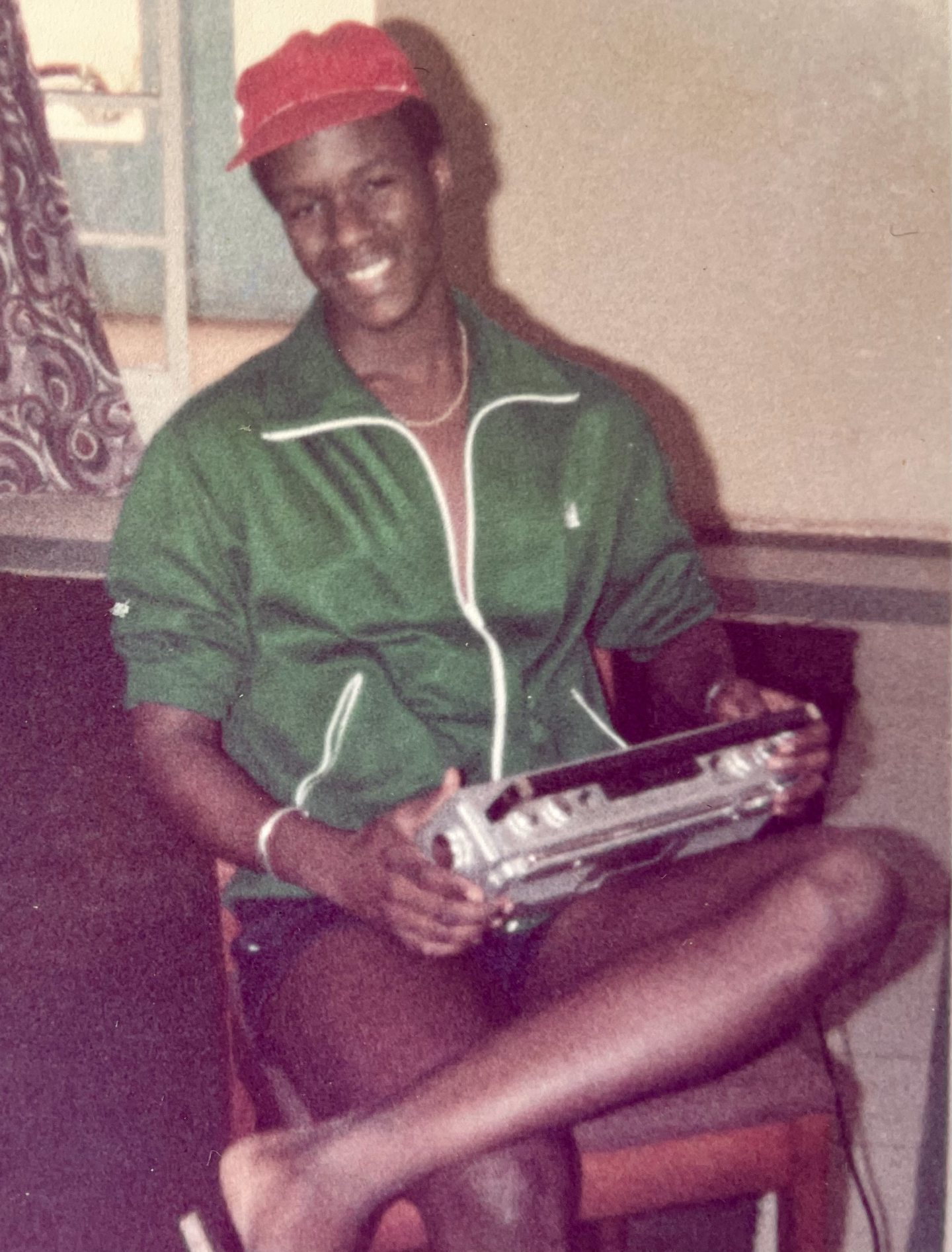

Back in what he calls his “beach bum” days in The Gambia, 19-year-old James N’Dow would gaze at the stars in the night sky and imagine jetting overseas to study at a top university.

At the time, he was working at a local hospital. His father was the head of the Gambian health service and James enjoyed — by the standards of The Gambia, where poverty and poor health are widespread — a privileged lifestyle.

But, he says, his life “was going nowhere”. Certainly not to Oxford, Cambridge or London where his star-dreaming reveries took him.

Then the phone rang. And his life changed.

“It was November 4, 1985,” James recalls. “I got a call that someone from the British Council wanted to see me and I had to go to my home.

“I thought, as the petulant 19-year-old that I was, that it was complete nonsense. So I went home and there he was, this chap from the British Council. And he was there to offer me a scholarship.”

It was great news, however he had never applied for a scholarship.

To this day, he has no idea how or why it was offered. His father, who studied medicine in Dublin and Edinburgh during the Second World War, may have held the answer but passed away a few years ago.

“I never did get to the bottom of it,” James says.

From The Gambia to Aberdeen, via a cold awakening

The scholarship was to study medicine in Aberdeen, and he flew almost immediately to London. Still groggy from the flight and the West African sun still in his bones, it was here that James had his first encounter with the British winter.

“It was late in the evening and looked quite beautiful white outside,” James recalls. “Then the doors opened and honestly I felt this was the end of my life.

“Nobody prepares you for zero degrees. Seriously, it’s impossible to imagine.

“The good thing was I had a one-way ticket. If I had a return ticket, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Things didn’t improve when James took the train north.

“Aberdeen the first year was honestly a nightmare. The people were lovely but I was sleeping in long johns, tracksuit bottoms, hat, gloves. I used to study at night but I could not focus after 9.30pm when they turned the heating off in my halls.

“So really it was the toughest year.”

James was also one of the few black students at the university, and though he says he was never treated badly there were some discomforting experiences.

“I used to have a bit more hair, and when you pulled it it would stand out,” he says. “So I had people sitting in the back [of the class] pulling it. Not maliciously, they had just never seen hair like mine before.”

Falling in love with a ‘Stonehaven lassie’

James quickly settled into the routine of medical school, but in that first year he viewed Aberdeen as a staging post. Never did he imagine that 40 years later he would still be here.

“I came with a clear intention that I would go back home,” he says. “The Gambian health sector has been challenged for years and for me that was my responsibility.

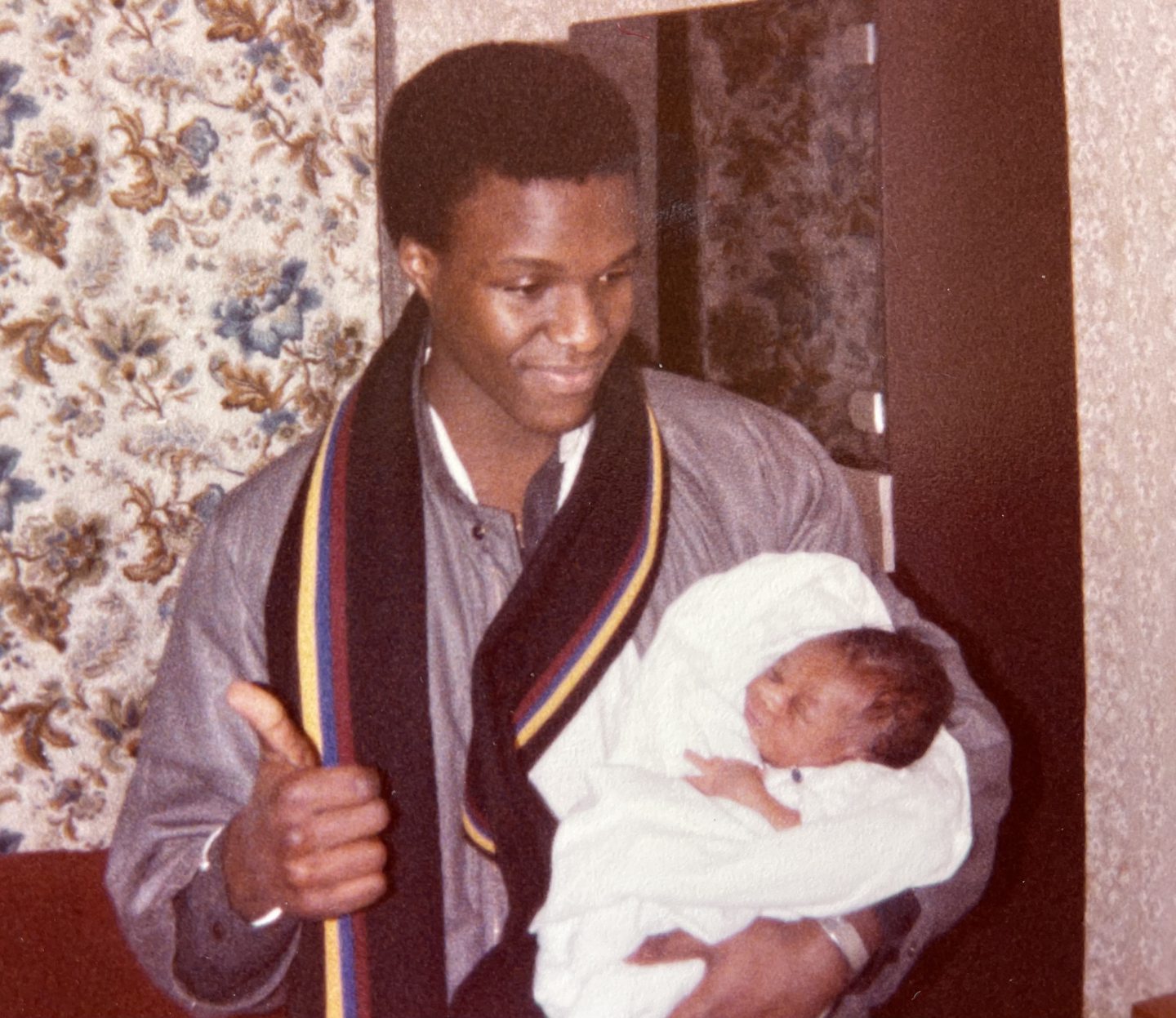

But on the first day of his second year he went to a cheese and wine reception and met Kathleen, a fellow medical student from Stonehaven.

Once more, James’ life jumped the tracks, though it was only later he only realised it meant spending the rest of his life in Aberdeen.

“I did not do my due diligence,” he says with a smile. “If I had done my due diligence, I would have known that Stonehaven lassies don’t travel well.”

‘They told us how hopeless we were’

James eventually entered general surgery at ARI. His first surgical job was in the urology ward, a move that kickstarted a glittering career in the field and eventual move — via specialist training in Newcastle – to consultant urological surgeon.

On the academic side, in 2001 he was appointed as the first director of Aberdeen University’s Academic Urology Unit and has published more than 170 research papers.

His ongoing work with the European Association of Urology, Europe’s leading body on urological practice, research and education, saw him head up the important guidelines office for seven years.

Meanwhile, a chastening dressing down in an Aberdeen hotel led him in 2005, with colleague Sam McClinton, to set up UCAN, the pioneering urology cancer charity that would serve as a template for the way patients are supported post surgery.

James had hoped for some honest feedback from the patients. He and Sam got that — and whole lot more in what ultimately to the launch of UCAN.

Says James: “They spent one hour and 15 minutes telling us how hopeless we were.

Nicola Sturgeon and a bus ad — how UCAN started

Set in a redeveloped ward on the fifth floor of ARI, the UCAN centre was intended as — and still is — a point of contact for urology patients who can drop in and ask about prostate cancer, testicular cancer or any other worry they may have.

The charity’s launch in 2008, overseen by then Scottish health minister Nicola Sturgeon, was in tandem with a prostate cancer awareness campaign, which memorably rolled out on Aberdeen buses in 2008.

UCAN was groundbreaking and helped shift focus on how to continue looking out for patients once they’d left the operating table, work that continues to this day.

James’ current UCan project is a one-stop shop where people can get all their diagnostics — consultations, prostate biopsies, MRI scans, pathology report cards — in the same place.

It would, he says, cut down on the unnecessary stress patients go through before they are diagnosed.

“Imagine the psychological impact of sitting at home wondering if you have cancer, when actually you probably don’t,” he explains. “That six months or four months of stress. It’s not normal, right? Not when we can do something about it.”

‘If you’re not depressed by that you’re not human’

James hopes the one-stop shop will be a reality before the end of the year, though he baulks at the suggestion his OBE would be useful leverage.

“If only you could convince me that that would work,” he laughs.

But it does bring into focus the current situation of the NHS, where funding for projects is generally in short supply.

“I am,” James states, “a lover of the NHS,” though he does acknowledge the huge budget deficits and the demoralising waiting times for patients.

“If you’re not depressed by that you’re not human.”

He adds: “I’m biased because I’m in the health sector, and involved in the developing world but I think all leaders must prioritise these health and education,” he says. “Take budgets from wherever you want, I don’t care. But health and education – these are for our kids and our grandkids.”

James gives back to The Gambia

James may not have returned to The Gambia to live, but he goes back about six times a year to oversee his charity, Horizons Trust UK, which works to improve the country’s currently inadequate pre-and-post natal care.

“In The Gambia, about 60% of people are living below the poverty line,” he says. “But the biggest tragedy is women dying in childbirth, where one-third of them bleed to death.

“If one woman in Aberdeen bled to death, there would be an outcry. It would be investigated by the Scottish government. In The Gambia when women bleed to death they are not even a recorded statistic.”

Will King Charles do the honours for James?

With the interview nearly over, I try one last time to talk about the OBE.

James laughs and deflects once more, nobly dedicating the award to all the people that work with him in ARI and elsewhere.

We chat about whether he will go down to London to receive it with his family, Kathleen and children Jegan, Samira and Kamal.

James has no idea what will happen, or if it will be King Charles who does the honours.

And then he relents, and gives me something.

We’ve just spent the past hour discussing his life story, so maybe he finally was able to put it all in context.

Whatever the reason, it’s a good way to end the story of the man who all those years ago opened the door at Gatwick and felt that icy chill.

“I’m hugely honoured about this,” James says of the OBE. “Because it was unimaginable for me back then, as a 19-year-old standing in the airport.

“It’s just something that doesn’t happen to you, right?”