Shortly before Jacqueline Robertson underwent surgery for oesophageal cancer, her consultant gave her an important piece of advice.

“She told me the operation will not make me better,” recalls Jacqueline, who had most of her oesophagus removed in the life-saving procedure. “She said it is going to get rid of the cancer, but it will leave you with a hidden disability.”

At the time, Jacqueline was happy to accept that outcome. She’s been diagnosed with late-stage cancer a few months earlier and had already gone through aggressive chemo to shrink the tumour. She just wanted the cancer gone.

It was only later, when the problems started, that she fully realised what the consultant had meant.

This was when Jacqueline’s remaining oesophagus, for reasons that are still unknown, had shrunk to half a millimetre in size, stopping even her own saliva from passing through and forcing her to vomit up her spit every 20 minutes.

Meanwhile, she couldn’t eat or drink and was being kept alive by a tube into her gut that fed her nutrients overnight.

At times, she regretted having the surgery at all even though she knew it had saved her life. She’d felt much better before the operation — exercising, eating and going on holiday with husband Anton and two children Emma and John.

Now, here she was, unable to eat and having to drain her saliva into the toilet.

“It was stupid to think like that because, guess what, the cancer was going to come back,” she says now.

“But I think we’re all psychologically geared to it — if something is wrong, you get surgery, it makes you better.”

It took her some time to accept that for her, this wasn’t how it was going to turn out. She would never get back to normal.

The symptoms that led Jacqueline to her oesophagus surgery

It all started with a touch of heartburn.

It wasn’t uncomfortable — nothing that a few indigestion tablets couldn’t fix. But one night, in a restaurant, Jacqueline suddenly couldn’t swallow her food.

It was October 2019, and at first, the self-confessed “yappaholic” thought she was just talking too much.

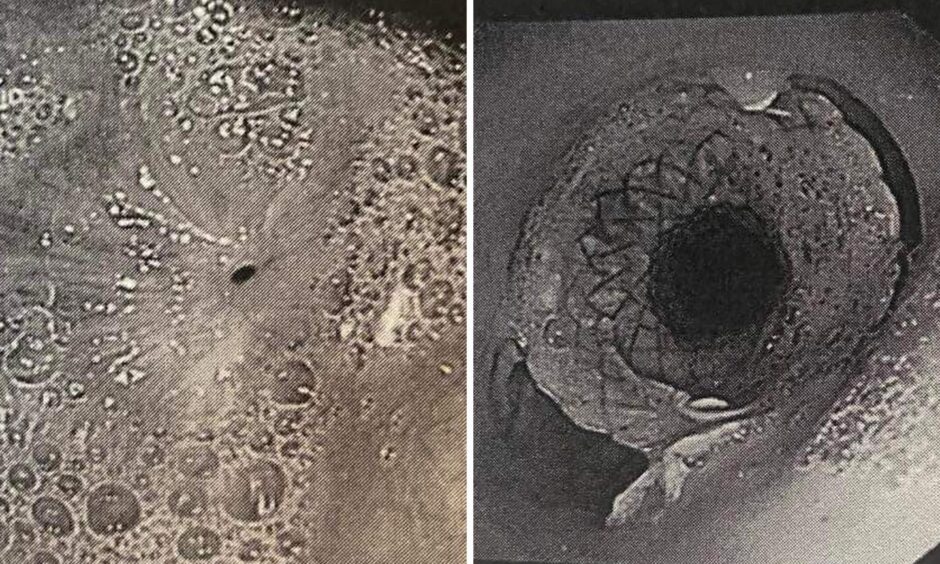

Eventually, she got it checked out, and in January had the first of what would eventually end up being 69 endoscopes — an uncomfortable procedure in which a camera is stuck the throat.

Biopsies were taken. By this time no one had mentioned cancer, and it wasn’t on Jacqueline’s mind. She thought her swallowing problems might have something to do with an old stomach hernia.

More biopsies were taken and time passed. Soon, an obstacle hooved into view; in March 2020, Covid-19 forced everyone indoors and suddenly hospitals had other priorities.

Finally, Jacqueline was called into the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary for results. She says she knew it was bad news because the nurse was surprised she’d turned up alone.

She was told she had “a genuine risk of it being cancer”. The assessment was confirmed later — she had stage-three oesophagus cancer.

A one in ten chance she wouldn’t survive oesophagus cancer operation

Surgery was set for October 16.

Oesophagus surgery involves removing most of the oesophagus and pulling the stomach up to fill in the gap. It is relatively complex and Jacqueline was told there was a one in ten chance she wouldn’t survive.

To make the most of their time together, the family booked a long weekend at a cottage in Perthshire; just the four of them and their dog.

“It was wonderful,” Jacqueline says. “I think subconsciously it was like this could be the last holiday that we’re all together. But we didn’t dwell on it. We didn’t think about it.”

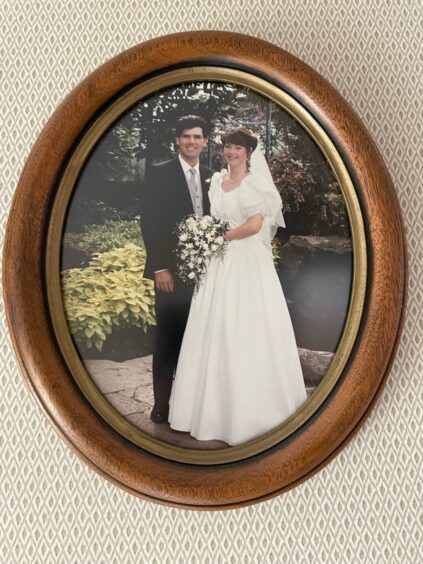

She and Anton dealt with it as they had in the three decades they’d been together since meeting in an Aberdeen nightclub in 1991. With no melodrama, and the sense that this is just one more challenge to get through together.

“My husband is one of the most amazing human beings that you could ever hope to meet. He is so caring and considerate and like me meets every challenge head on. And that’s what we were doing at that point.”

The eight-hour surgery removed the tumour completely and though a two-week hospital stay turned into nine weeks, it was with huge relief that Jacqueline eventually returned home.

Daughter Emma put balloons up around the house.

Jacqueline looked forward to some normalcy at last.

‘I couldn’t even have a cup of coffee’

Because the operation was in October, Jacqueline expected to be feeling a lot better by Christmas.

When the holidays came round, however, she was struggling. She couldn’t eat; she couldn’t even swallow her own saliva.

She didn’t know it at the time but her oesphogus had shrunk to half a millimetre in width. The saliva she produced in her mouth had nowhere to go and was pooling about 10 centimetres down her gullet, triggering the gag reflex.

If Jacqueline was having a conversation with someone, she would have to excuse herself every 20 minutes to go to the bathroom. There, she would throw up all the saliva that had built up at the blockage.

“I couldn’t drink water,” she says. “I couldn’t even have a cup of coffee, I couldn’t do anything.”

Why 2021 was Jacqueline’s worst year

Jacqueline calls 2021 her worst year.

Various attempts to widen her gullet were tried, but all failed.

Her consultant eventually inserted a small mesh tube, 12 millimetres in width, into Jacqueline’s throat. The mesh allowed Jacqueline not only to swallow her saliva, but to eat a small amount of food for the first time in months.

“One day I had some pasta and some macaroni and cheese,” Jacqueline says, smiling at the memory. “These things blow your mind when you haven’t eaten for three months.”

But the mesh would only last for four weeks. There was no time for Jacqueline’s body to recover so she was hardly eating. Her weight dropped precipitously.

A new mesh was used — this time a biodegradable one that was still being tested.

Jacqueline was one of the first patients in Aberdeen to try it, and it proved to be the answer.

Instead of four weeks use, Jacqueline was getting four months — “a massive difference,” she says.

She started putting weight back on. She was able to travel down to Wales to meet an old friend. It wasn’t perfect, but she could live with it.

“If someone had told me in 2020, you’re going to have this operation and you’re going to have to come into hospital every four months for the rest of your life, I would have laughed at them,” she says. “But it’s relative, everything’s relative.”

‘Nobody likes the thought of a camera down their throat’

Because her doctor still replaces the mesh every four months, Jacqueline is classified as a palliative care patient. If the procedure didn’t happen, she would die.

But as she points out brightly: “I’m not dying.”

Indeed, sitting in her front room in Aberdeen with dog Brüna she looks to be thriving.

She is able to swallow her saliva, which means she can get back to talking – not that she admits to ever stopping.

And though she can’t eat everything she wants – for example, she can eat the topping of a bruschetta but not the crisp bread base – she is able to enjoy the sensation of chewing again.

None of it would have been possible, she says, without the amazing team at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary — all of the doctors and support staff without whom she wouldn’t be alive.

Meanwhile, she has a message to pass on. If you suspect something is not right, get it checked out.

“Nobody likes the thought of a camera down their throat because it’s invasive,” she says. “But I’m sure you would rather have one camera down your throat than have three years of it.”

What lies ahead for Jacqueline after her oesophagus cancer

Next October marks five years since Jacqueline’s surgery to remove her cancer. After that, she will no longer have to go for the routine scans that are a precaution against the cancer returning.

Life may never return to normal, but she is happy at where it has ended up.

“All these corny quotes are actually true,” she says.

“When you’ve gone through what I’ve been through, it’s about being aware of what you’ve got, and being grateful for it.”

Conversation