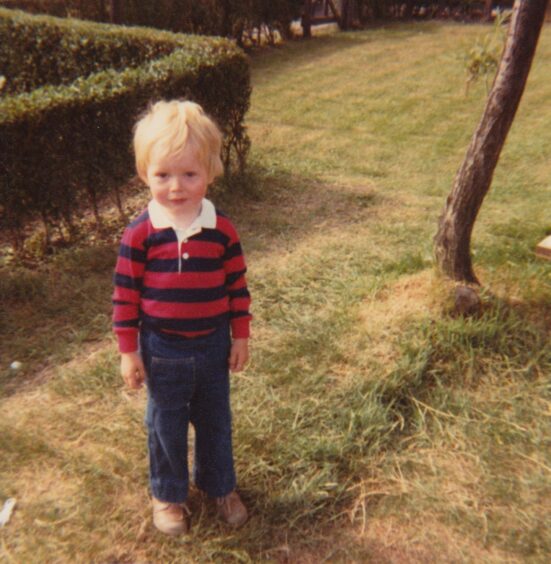

When Martin Reid was a boy he loved going to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary with his granddad to help him with his blood product injections.

The two had a special bond. Both Martin and his grandfather Isaac Middleton — an Aberdeen taxi driver — were haemophiliacs and the trip to the hospital was treated as a learning experience.

Martin even rolled the vials containing the Factor VIII blood-clotting protein in his hands to warm them up before they were injected into Isaac for his haemophilia.

What he didn’t know was that at least one batch of Factor VIII his grandfather used was contaminated with hepatitis, a condition that Martin believes contributed to Isaac’s death in 1997 aged 71.

“You had to sit and roll it in your hands for 10 to 15 minutes until it got to room temperature,” explains Martin, who also contracted hepatitis through contaminated blood products. “But unwittingly, I was sitting there helping my grandfather make up the treatment that potentially infected him.”

Is the contaminated blood scandal the biggest in NHS history?

Martin and Isaac were two of the estimated 3,000 people in Scotland, and thousands more in the UK, given contaminated NHS blood and blood products in the 1970s and 1980s.

Many of those, including Martin and Isaac, developed Hepatitis C, a condition that can cause potentially fatal damage to the liver. A smaller group contracted HIV. Some contracted both.

It has been called the biggest scandal in NHS history, in part because the contaminated blood came from unscreened sources.

Donors included prisoners and drug addicts in the US who were paid for their donations.

Meanwhile, medical staff at the time have been described as having a ‘paternalistic’ approach to patients affected by the contaminated blood.

Many were not told they had contracted a virus, their worsening health condition blamed on other factors such as alcohol or drug use.

For haemophiliacs like Martin and Isaac, the contamination was in clotting factors they used to control the condition, with Factor VIII the principal carrier. In Scotland, 480 people with bleeding disorders such as haemophilia were infected.

Contaminated blood inquiry report set for release

Now, however, the long-running campaign to get justice for victims may be ending. Monday May 20 will see the release of the report from the Infected Blood Inquiry, launched in 2017 and chaired by former High Court judge Sir Brian Langstaff.

Over the past seven years, the inquiry has heard from hundreds of witnesses either directly affected by contaminated blood or family members who watched loved ones die or their health deteriorate.

When released, the report is expected to finally give an answer to why so many men and women were given contaminated blood and blood products, what size of compensation is required and whether there was a cover-up in government and medicine.

‘I compare it to the Piper Alpha disaster’

Martin, who is one of hundreds to give a witness statement to the inquiry, has heard the upcoming contaminated blood report likened to the ongoing Post Office Horizon inquiry, which was brought to national attention by ITV programme Mr Bates vs The Post Office.

However, the 43-year-old graphic designer who grew up in Mastrick in Aberdeen and now lives in Oyne, Aberdeenshire with his wife and two children, says the NHS blood scandal even goes beyond other tragedies because of the length of time victims have waited for justice.

“When I’m talking to people about it, I compare it to the Piper Alpha disaster, especially in this part of the world as everybody knows the terrible incident that happened,” he says.

“But also afterwards there was a massive investigation and things were put in place to make sure that that something like that would never happen again. And unfortunately in this scandal we’ve seen some people who’ve been waiting 50 years to get answers as to why this happened.”

He adds: “Since the inquiry started, and all the evidence that has come to light, it shows that the doctors and the government knew that there were issues with these products, but they just kept giving them to us.”

Martin hopes the report will paint a full picture of the mistakes that were made and offer recommendations to ensure nothing like this can happen again.

“I also hope that for many people, including myself, we get answers to the pieces of the puzzle of our life that are missing.”

The only paediatric case in Aberdeen?

Martin believes he contracted hepatitis C when he was four, though his family were told when he was eight.

Haemophilia ran in the family — as well as his grandfather, his mother Jacqueline and brother carried the gene.

Only Martin and Isaac, however, contracted hepatitis C through the contaminated blood. In fact, Martin believes he was the only paediatric case in the whole of Aberdeen.

“I won the crap lottery,” he says ruefully.

At school, he endured cruel taunts in the playground. In the 1980 and early 1990s, hepatitis C was widely misunderstood and often confused with HIV, a condition that at the time was portrayed as a death sentence.

“I got bullied for about six months,” Martin says. “I got called AIDS boy, terms such as homosexual, poofter. It was quite a quite an eye-opener as a 14-year-old.”

Martin’s heartbreaking final gesture for grandad Isaac

Martin was 17 when his grandfather died. Isaac’s medical records recorded his death as caused by his liver and bowel cancer, but Martin and his family firmly believe the liver cancer was caused by his hepatitis B and C.

The death affected Martin deeply. Martin remembers going to the newsagents to buy the Sunday papers and then placing them in Isaac’s open coffin.

“It was the last thing I could do for him,” he says.

But Isaac’s passing was not just the loss of a best friend for Martin.

“Seeing my grandfather going through the final stages of his life was what I thought lay ahead for me,” he says.

“And from losing my grandfather onwards, it felt like there was just this dark cloud hanging over my head.”

How Martin’s family struggled with guilt

Martin calls himself one of the lucky ones.

His heamophilia is classed as ‘mild moderate’, which means he only requires hospital treatment when having dental work, for example, or suffers an injury.

Meanwhile, his hepatitis C was successfully treated shortly with recombinant interferon, a therapy that can clear some viruses. It was shortly before he got married and he says he wanted to be free of his condition before he had children.

Though his daughter Elizabeth is a carrier of haemophilia and he worries about her passing it on to her children (haemophilia mostly affects male), his son does not have the gene.

Martin’s son is called Isaac, named for his great-grandfather.

But his family has struggled with feelings of guilt now for generations; Martin says his grandfather was conflicted about passing the haemophilia gene on to him.

Meanwhile, similar to many parents of children who were given contaminated blood, Martin’s mum and dad, who still live in Mastrick, felt in some way responsible.

“My mum and dad both left with a severe sense of guilt that they simply took their child to hospital to get treatment for haemophilia and ended up coming out of the hospital with a virus that potentially could kill him,” he says.

“And because my mum and dad had seen the process my grandad’s health had went through towards the end of his life, I know they were terrified that that’s what lay ahead for me.”

The human toll of the contaminated blood scandal

It is only recently that Martin has felt able to talk about what happened to him. His witness statement to the inquiry, and the many other statements from fellow victims, showed him the benefit of revealing the human impact of the scandal.

He recalls watching one mother tell how she discovered her son had HIV from a list pinned to a wall in a hospital ward. Another mother talked about how her dead son had his coffin nailed shut because he had HIV.

He says: “I’ve had a lot more time to reflect on my own history, and what happened to my grandfather. It’s that realisation that something really terrible did happen to you in your life. Because no one has listened to you for 35 years, you become very good at hiding it.”

‘No amount of money to make up for that’

Martin was one of the victims awarded £100,000 in compensation as part of a government-funded interim settlement in October 2022.

But he says money is not the priority for many affected by the contaminated blood scandal.

“Everyone who’s been caught up in this deserves some sort of financial recognition,” he says. “But because you did get money into your bank account, that doesn’t mean what you’ve been through suddenly vanishes overnight.

“There are thousands of people out there who had to give up their work, who lost their homes, who lost their marriages, whose relationships with their families totally broke down and in many cases people who sadly died.

“There is no amount of money to make up for that.”

Meanwhile, he says the report is a chance for closure, for families and victims alike.

“They just want someone to take responsibility and say, sorry, we got it wrong. And we will do our very best to make sure that something like this never happens again.”

Conversation