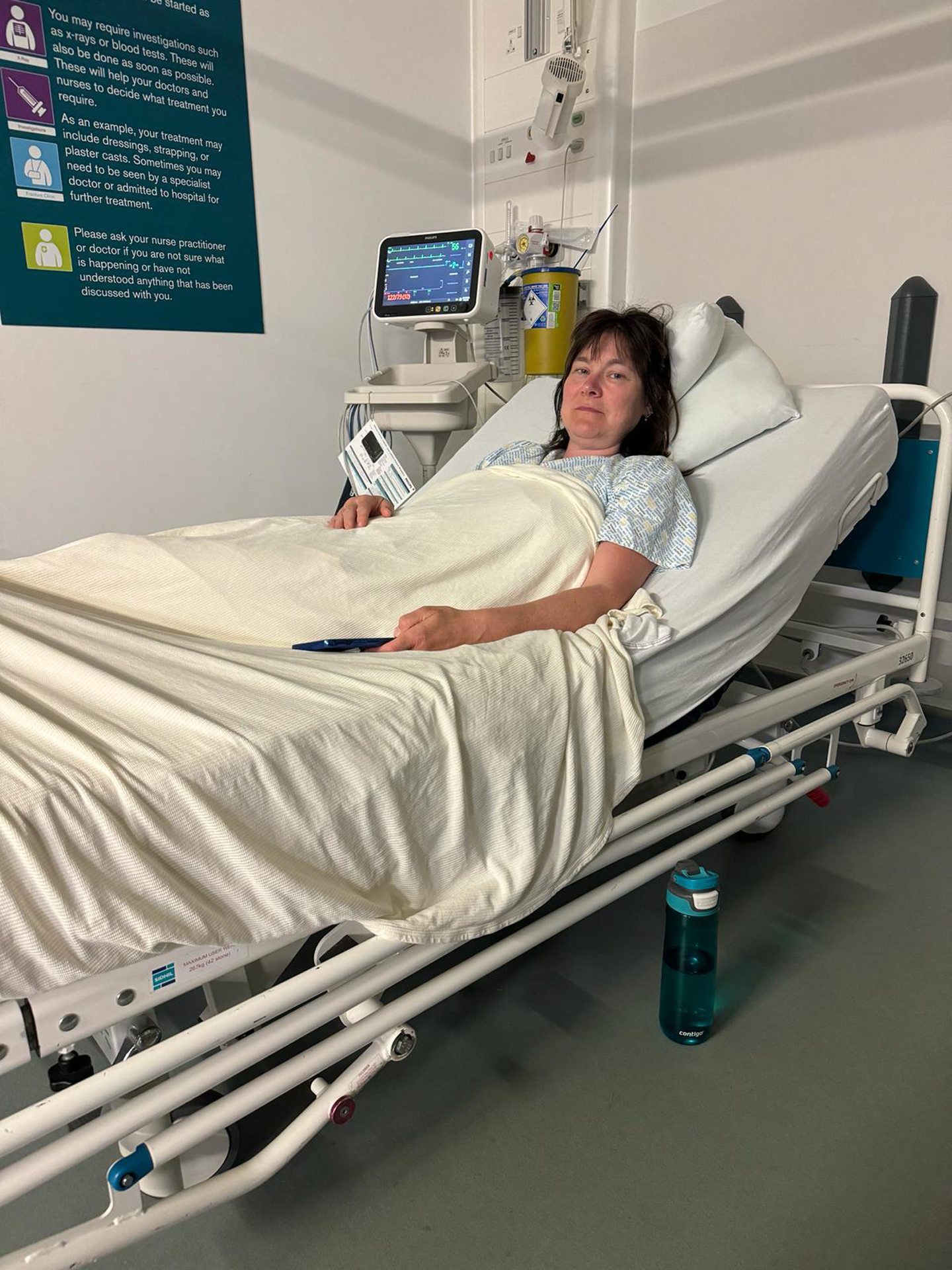

When Maggie Watson had a heart attack last month, her first thought was, “why me?”

The Banchory mum is a long way from the traditional idea of a coronary victim. For a start, she’s only 49. And she’s fit and healthy — she walks up local landmark Scolty Hill at least three times a week.

Even when the doctors told her she’d suffered a spontaneous coronary artery dissection, or SCAD, she didn’t understand.

She’d never heard of the term.

But it turns out Maggie WAS the perfect model for a heart attack, one in SCAD form at least.

Because the little-known condition, which is as likely to affect healthy people as non-healthy, is a leading cause of heart attacks for women under 50.

It also cannot be predicted and so far there is no way to prevent one happening.

“It was scary,” Maggie says. “My husband is slightly overweight, and I said to him, why is it me? I thought I would be the healthier one.”

A tea-time WHAM in the chest out of nowhere

Maggie was introduced to SCAD, like nearly all its victims, out of the blue.

It was May 5 and she’d just finished her tea. She went through to the living room to sit with her father-in-law’s dog she was looking after when, WHAM!, she felt a large, compressed pain in the middle of her chest.

She lent forward to try to relieve it. That didn’t work, so she went into the kitchen where her children were still eating.

That didn’t help either, though for different reasons.

“I said, I’m not feeling right,” Maggie recalls. “And of course, they were all on their phones, ignoring me.”

Maggie eventually called 111 but the queue was an hour and a half long. So she did was many people would do in the same situation — she called her mum.

It was just as well she did, because her mum immediately told her to call 999, a move that ultimately may have saved Maggie’s life, though it still took time.

The paramedics came within half an hour but Maggie endured an extended stay in the loading zone of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary due to a shortage of available beds.

Even when offloaded she was initially stuck in a corridor.

“I didn’t like it,” Maggie says. “I mean, you definitely leave a bit of dignity behind.”

The nurse that saved Maggie’s life

Meanwhile, no one seemed to know what was wrong with her.

Perhaps because she wasn’t a typical victim of a regular heart attack, the paramedics thought Maggie had suffered a spasm, which can be similar to a heart attack.

However, a nurse told the paramedics that women do not always present the usual symptoms for heart attacks and ordered a blood test.

That test revealed Maggie’s bloods were up — she had indeed had a heart attack.

If it hadn’t of been for that nurse (“I’d love to shake her hand,” says Maggie”) the consequences could have been dire.

At the least, it allowed Maggie vindication with her family who, in typical fashion, were poking fun at her.

“My husband was laughing, saying I’ve got the ambulance out over a spasm,” she chuckles. “They were all thinking it was quite comical.”

What is SCAD and why does it affect women?

There was nothing funny about Maggie’s condition, however.

A SCAD is a serious condition when a tear appears in the wall of a coronary artery.

That allows blood to flow into the space between the layers and a clot forms, which in turn reduces blood flow and potentially triggers a heart attack.

Concerningly, the attack happens with no warning.

According to the British Heart Foundation, anyone is at risk though it is most common in women their 40s and 50s. Studies show that more than a third of heart attacks in women under 50 are SCAD.

And while little is known about why SCAD happens, it is much more common in women who have given birth.

Though pregnancy-related SCAD makes up a small percentage of all SCAD cases, it is the most common cause of heart attacks during pregnancy, according to the American Heart Association.

In Scotland, an estimated 50 people a year have a heart attack caused by SCAD and the NHS is beginning to ramp up efforts to tackle the condition.

Last year, health chiefs set up a pilot clinic in Forth Valley Royal Hospital near Falkirk to improve treatment.

After a few months, the clinic was receiving referrals from across Scotland, including Orkney.

How Maggie is dealing with the after-effects of SCAD

Since her heart attack, Maggie has read as much as she can about SCAD. She wonders if the fact she’s had five children had something to do with her episode, given the post-partum increase in risk.

What she doesn’t try to think about is what might have happened if the nurse hadn’t caught the signs of SCAD and ordered the blood test.

“I might have walked up Scolty hill and that might have been me,” she says. “You just don’t know and that’s scary.”

She is now under doctor’s orders to take it easy, which is exactly what she’s doing.

She was meant to be on holiday in Belize, the Central American country where her daughter lives, but that has been cancelled.

Also, a plan to climb Ben Nevis before she was 50 has been shelved.

“My daughter is still doing it. I’ve said to her she’ll just have come back and do it with me hopefully, in the next couple of years.”

But the hardest part of her recovery has been mental. The heart attack has left her feeling more vulnerable, a common symptom in post-SCAD patients.

The condition’s unpredictability can make life tough for victims.

“It’s fairly played with my mind,” she says. “Sometimes it’s not just the physical recovery, it’s the mental recovery — thinking, well, this could just happen again.”

She has, however, discovered a new sense of determination since the attack, one that.

She adds: “My youngest son did say to me at one point, are you going to die? I said, no, not if I can help it.

“Whatever doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger.”

Conversation