It is late Friday afternoon and Elizabeth Ajimisinmi is playing in the front room of the house in Aberdeen she shares with her mum Adeola and brother Testimony.

The eight-year-old has sickle cell anaemia, an inherited disorder that affects the oxygen-carrying red blood cells.

It is a serious condition that can be fatal, though for Elizabeth, who has treatment to manage it, the main symptom is the onset of a sickle cell ‘crisis’.

That’s when the blood cells get stuck in the blood vessels and cause severe pain, often in the chest, arms or legs. A crisis can put Elizabeth is in hospital for several days.

Because of this — and the fact she gets easily tired — her mum needs to keep a constant watch on how much energy Elizabeth expends.

A tricky proposition when you’ve got an excitable eight-year-old determined to make the most of her Friday evening after school.

“Can I play football?” Elizabeth is asking as she bounces off the sitting room sofa.

Her mum holds her thumb and forefinger slightly apart. A little bit, she is saying.

Elizabeth looks up. She has a huge grin on her face. Quietly, so her mum can’t hear, she whispers conspiratorially, “I CAN play football”. And off she zooms.

Living a normal life, but with sickle cell limits

Elizabeth can do a lot of things. She’s just started learning the cello AND double bass at the primary school she and Testimony attend in Aberdeen.

Meanwhile, she’s already really good at football (or so she claims). And one day when she’s older she’s going to “sing in front of 10,000 people” (location and song yet to be determined).

Her sickle cell anaemia, however, means that limits need to be placed on her, something that grates against her natural enthusiasm.

“She’s still a child,” says mum Adeola. “She doesn’t know her limits so I have to constantly remind her.”

When she is healthy, everything is fine. She goes to school and plays with her friends. Life can be normal.

But there is always the danger another crisis will hit.

It can, says Adeola, come out of the blue — even when she sticks to the treatment rules such as keeping Elizabeth warm, hydrated and well rested.

“She can be well now but you don’t know what will happen in the next few minutes,” Adeola says. “I don’t even know if I’m going to sleep in this house today or tomorrow.”

Elizabeth’s teachers know about her condition so can watch out for signs of a coming crisis like extreme tiredness, shortness of breath or dizziness.

But when one hits, the whole family go to hospital.

“I explain to her that it’s not her fault,” Adeola says. “She is afraid of the hospital because she knows they will try to put a line into her arm so that they can give her medication, like antibiotics.

At the hospital, Testimony, who is six, makes sure his big sister is well looked after.

“He tells the doctors to be careful with her,” Adeola says.

Sickle cell pain made Elizabeth a ‘crybaby’

Adeola is grateful for the treatment her daughter gets at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

Elizabeth was born in Lagos, Nigeria and initially doctors there failed to correctly diagnose the condition (sickle cell anaemia is more common amongst people of African or Asian origin).

She cried a lot, and initially, Adeola thought Elizabeth was just one of those babies.

“She would scream at night so I would feed her. But she’d still cry. You’d pick her up but she was still crying. Everyone said, oh this one is a crybaby.”

But she also noticed Elizabeth’s crying got louder if her hand was touched. She didn’t know it was a symptom of sickle cell, which inflames the limbs.

Learning the dos and don’ts of sickle cell anaemia

In the end, Elizabeth was in hospital for a month.

Adeola remembers it as a harrowing time. Treatments were tried but nothing alleviated the pain and Elizabeth didn’t improve.

One day, when hospital staff thought Adeola was sleeping, she overheard one of them say the only thing left to do for Elizabeth was pray.

But things changed after Adeola was put in touch with a sickle cell charity.

The foundation told Adeola how to manage Elizabeth’s condition by adhering to some dos and don’t.

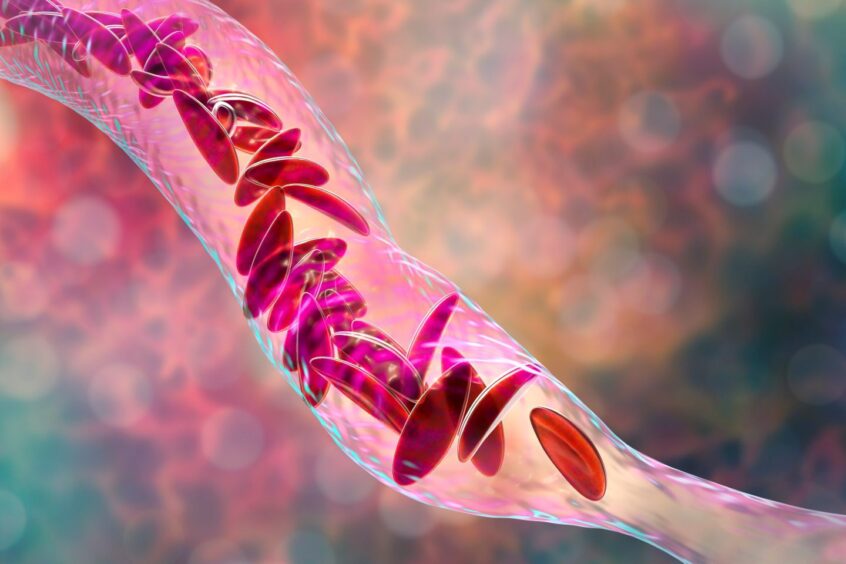

The extreme pain of a sickle cell crisis is caused by the red blood cells changing shape — into that of a curved sickle — after the oxygen in them has been released.

The red blood cells then stick together, causing blockages in the small blood vessels.

To stop this from happening, people with sickle cell anaemia stick to four core rules:

- Drink plenty of fluids;

- Don’t get too hot or cold;

- Dtay away from places with high altitudes where oxygen levels are low;

- And avoid anything that makes them very tired.

‘Even in my dreams they are expensive’

Thanks to the rules, Elizabeth’s crises subsided — not completely but enough to make a difference.

And Adeola sticks to them to this day, though moving to from Nigeria to Scotland — and then from Glasgow to Aberdeen last year — has made it that more challenging to keep Elizabeth warm.

Moreover, as a single mum bringing up two children, Adeola has money concerns to contend with. Knowing Elizabeth may have to deal with sickle cell her whole life adds to those fears.

“I get scared about things, especially when she’s in crisis,” Adeola says. “Doctors may well come up with different cures for sickle cell but in my dreams I cannot afford it. Even in my dreams they are expensive.”

Recently, a friend put Adeola in touch with Family Fund, a UK grant-making charity for disabled and seriously ill children. The fund pays for essential items such as kitchen appliances, clothing, bedding, sensory toys and computers and last year provided grants and services totalling more than £32 million.

With Family Fund’s help, Adeola bought a new bed to replace a broken one. She also got a laptop for Elizabeth, which has been invaluable for her school work and as a creative outlet.

And after getting past her astonishment it was free — “Nothing is free in Nigeria!” — Adeola now encourages other low-income families to use the fund.

“It was a saving grace,” she says. “I couldn’t afford it and they came through for me. It was a whole lot and I’m so grateful for that.”

What will happen to Elizabeth’s sickle cell anaemia in the future?

The afternoon has become evening, and Elizabeth’s earlier energy has disappeared, replaced with an emotionally-charged tiredness. A sibling argument with Testimony sees her snuggling into her mum, who covers her in a giant hug.

With Elizabeth cocooned in her arms, Adeola keeps talking.

She mentions the future; how it was something she used to worry about for her daughter but is now slowly coming to terms with. Meanwhile, she is doing her best, and that is the most she can do.

She says one question Elizbeth always asks is whether she will have sickle cell anaemia when she is older.

It is a question Adeola can’t yet answer. There is a cure for sickle cell but the risks of the bone marrow transplant it requires means it is not often used. New treatments are being approved for use in Scotland, but nothing is definite with this type of condition.

“Things might change,” Adeola says to Elizbeth, almost hidden in her mum’s embrace. “We don’t know what the future holds.”

For more information on Family Fund and to check if you may be eligible for support visit www.familyfund.org.uk.