Hussein Patwa is one of Scotland’s best target rifle marksmen, an expert at shooting .22 caliber bullets at a bullseye 10 metres away and not much bigger than a pinhead. He is also blind.

“It’s a fantastic conversation starter,” the Aberdonian says with a grin. “There’s either a gasp, a pause or a ‘How on earth do you do that?’

Welcome to the world of acoustic rifle shooting, a sport designed for the visually impaired.

On the surface, there’s not much to differentiate it from the target rifle shooting on show last week at the Paris Olympics.

The rifle is the same competition gas-powered air rifle, as is the scoring system.

In fact, the only difference is that instead of a visual scope competitors use an audible one that lets them aim with sound instead of sight.

The higher in pitch the sound, the closer they are to the centre of the target.

Hussein’s gold haul and Paralympic ambitions

Hussein has been an acoustic rifle shooter — off and on — since 1998 when he showed up at an open day at the Denwood Target Shooting Centre just off Aberdeen’s Countesswells Road.

He loves it. And he’s very good at it.

Last month, at a national event in Swansea he took home two gold medals in his favoured discipline, the 10-metre bench rest, a seated variation that requires intense concentration and the ability to sit perfectly still for just under hour.

But he is also at the forefront of a movement that could result in a fundamental shift in competitive shooting — perhaps even disabled sports as a whole.

He believes that one day soon, blind athletes like himself will go head-to-head against sighted athletes in elite shooting competitions such as the Paralympics.

As he says of his sport: “The only thing that makes a difference is that I use my ears and they use their eyes.”

What is acoustic rifle shooting?

It is Thursday night — practice night — and Hussein is at the Denwood range with Aberdeen’s small group of acoustic rifle shooters.

To the psht, psht sound of the compressed gas cylinders being prepared for the air rifles, Hussein explains the origins of his sport.

It is a curious story.

Acoustic shooting started when the Austrian jewelry company Swarovski — which has a sideline in optical scopes — accidently discovered it could turn reflected light into a noise when hooked up to an oscilloscope.

That resulted in the Swarovski rifle scope, which for years was the basis of acoustic rifle shooting.

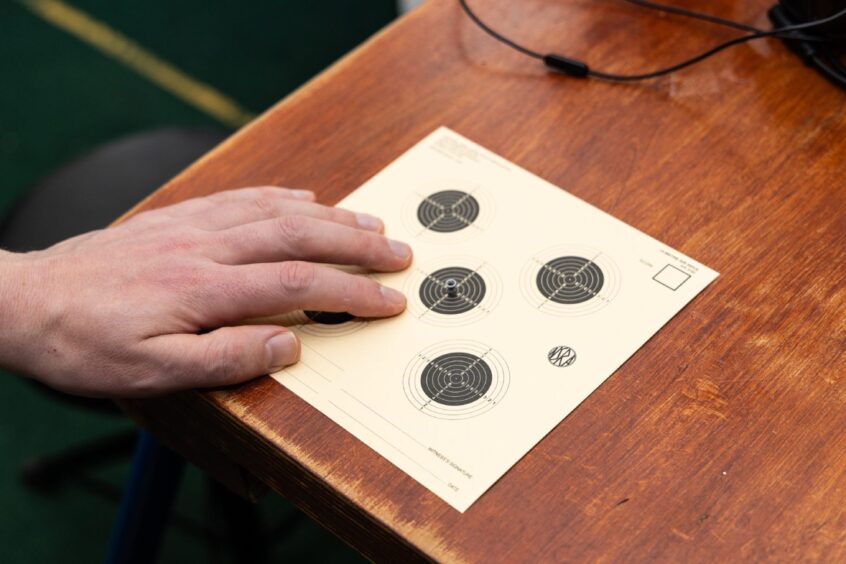

Participants fired at a paper target hung below a halogen light, which the scope used to determine the distance from the bullseye then transferring that measurement into sound.

The Swarovski scope is still used by beginners, but these days most competitive shooters have an electronic scope fitted with a high-speed camera. The set-up uses the same basic principles as the Swarovski scope but is more accurate.

It also gives instant feedback on where shots land via a monitor that sits by the shooter’s shoulder.

Also, no paper targets are used. As in all competitive target shooting these days, whether sighted or visually impaired, hits are measured using tiny microphones embedded in the target.

Why Hussein started competing against sighted rivals

You could say Hussein’s mission to compete against sighted athletes began two years ago.

He is not totally blind — he has some peripheral vision — but his condition, retinitis pigmentosa, is degenerative and means that he will eventually have no sight at all.

Two years ago, however, he was encouraged by his coach, Jim Cole-Hamilton, to switch from seated prone to bench rest shooting.

In prone, the full weight of the rifle is carried by the shooter, something Hussein always found uncomfortable.

In bench rest, the rifle sits on a bench or table. It is physically easier, but it is a more intense, technical discipline that requires focussed concentration to fire the regulation 60 bullets in 50 minutes.

Hussein took to it immediately. The 38-year-old freely admits to a slightly chaotic lifestyle (“I’m certainly not a tidy person, put it that way,” he says) but when shooting, he tunes into the meditative-like zone that top competitors need at the highest levels.

“He is a machine,” remarks John Gaskell, a former Scottish open shooting champ and one of the volunteers that make Thursday night practice possible for the acoustic rifle club.

In 2022, Hussein won the first bench rest competition he took part in. He calls it beginners’ luck. But he is being typically modest, because the athletes he beat were sighted.

‘The voices are getting louder’ for acoustic rifle shooting

Hussein has now competed against sighted shooters on eight separate occasions. In 2023, he added one more win to his Yorkshire success and came second in another in Cambridge.

Now though, he is setting his sights higher. Target shooting is a Paralympic sport, but as it stands there is no category for visually impaired shooters.

If Hussein gets his way, that will change. It’s too late for the Paris Paralympics, due to start on August 28.

But Hussein is adamant it will happen in either the 2028 Summer Paralympics in Los Angeles or 2032 in Brisbane.

“The voices are getting louder,” he says. “It’s not going to be too long before we break that ceiling.”

What does rest of the sport think of Hussein’s efforts?

Hussein may not have it all his own way.

For a start, he’s not entirely sure what the rest of the shooting community thinks about him and his audible scope.

He says he’s had nothing but encouragement, but tells the story of returning the following year to the Yorkshire competition he won and seeing the average score from rivals jump by 10 points.

“We had this joke in the club,” he recalls. “There’s probably people up and down the country going, ‘Who the hell is this Patwa guy? A blind guy from Aberdeen? Oh, we are not having that.’”

There is also a chance Hussein is knocking on a locked door.

Tyler Anderson, senior manager for World Shooting Para Sport, which oversees Paralympic shooting, said there are “currently no plans to integrate vision impaired shooting into able body shooting”.

He added: “We do have plans to make VI shooting a Paralympic Games event, which we have applied for the Los Angeles 2028 Paralympic Games.”

The Celine Dion effect on acoustic rifle shooting

But there are other, even subtler barriers. The recent competition in Swansea was held in a tennis centre, with an indoor Tannoy blasting out pop music — not the most conducive atmosphere for people who aim with their ears.

“It happens quite a lot with competitions,” Hussein says. “You could literally sit there with Celine Dion in the background, and you have to block it out.”

Conversely, competition rules mean that coaches are not allowed talk to their athletes, putting visually impaired athletes who are unable to see where their bullets hit, and make the corresponding adjustments, at a severe disadvantage.

To counteract that, Hussein and his coach have worked out a detailed signaling method. Jim traces lines on Hussein’s back with his finger to indicate how far off-centre the last shot was.

“That, again, is us trying to emulate what happens internationally,” Hussein explains.

Meet the Denwood acoustic rifle shooting crew

At Denwood, Hussein is halfway through his practice. He sits perfectly still, making his way through the tray of bullets that always sits the same distance from his hand.

Behind him, Jim notes each shot and silently draws his instructions across Hussein’s shoulder blades. Two clicks up, a click left.

To Hussein’s left are two other acoustic rifle shooters. Amanda Foster, who showed up to that same open day as Hussein in 1997, is on another electronic scope, easing through her bullets.

John Mitchell, a new recruit to the sport, is at the far end on a Swarovski scope.

A former Royal Navy gunner with macular degeneration, John was used to slightly larger caliber weapons until one day, aged 48, he walked out on deck and his world turned pink.

“The sea, the sky, everything,” he says.

Since then, his vision loss has progressed and he now only sees outlines against a white fog. Not that it stopped him from taking up shooting.

He also recently started ten-pin bowling.

‘When I go home even my wife sees a difference’

When the group break for a rest they are all smiles.

“I leave here on a Thursday night with a buzz,” says Hussein, who feels time fast forward when he’s on the range. “When I’m shooting, I find it does ground me. It centres me.”

“Big time,” agrees ex-sailor John. “When I go home even my wife sees a difference.”

All of the group wish they could practice more, but a lack of funding means they rely on the generous help of volunteers Jim and John, as well as third helper Ronnie Kain.

Meanwhile, Hussein — who has a day job as the co-chair of the Aberdeen Disability Equity Partnership — admits acoustic shooting is not the most accessible of sports.

The scopes cost as much as £1,600 each, compared to £400 for a regular scope, and travel expenses to competitions around the UK mount up.

Even getting out to the shooting range is expensive, and Hussein and Amanda share the £20 taxi fare as often as they can.

One question remains, though — if Hussein’s lobbying to get acoustic rifle shooting into the Paralympics is successful, will he enter?

We will have to wait and see.

“I enjoy just seeing how I can better myself,” he says. “But I’ve made a choice, and I want to see how far I can push that.”