Jovi Fawcett is making up for lost time.

The 26-year-old from Banchory was diagnosed with a rare blood disorder in her final year of secondary school. Without continuous treatment, she was told, she would live for just five years.

Then, during the summer of 2020 when Covid was at its peak, she was held in an ICU ward with life-threatening sepsis – an isolating and “alien” experience during which her only contact with her family was by phone.

So, now, when she’s offered the chance by cancer charities to do something she loves – like spend five magnificent days of the summer sailing around the west coast of Scotland – she jumps on it.

After all, she’s earned it.

“People can look at the things I do, such as the sailing trips, and think, ‘Oh, why does she deserve that?” she says.

“And this is why — because there are things that I had to miss out on.”

Banchory woman back onboard and reconnecting with friends

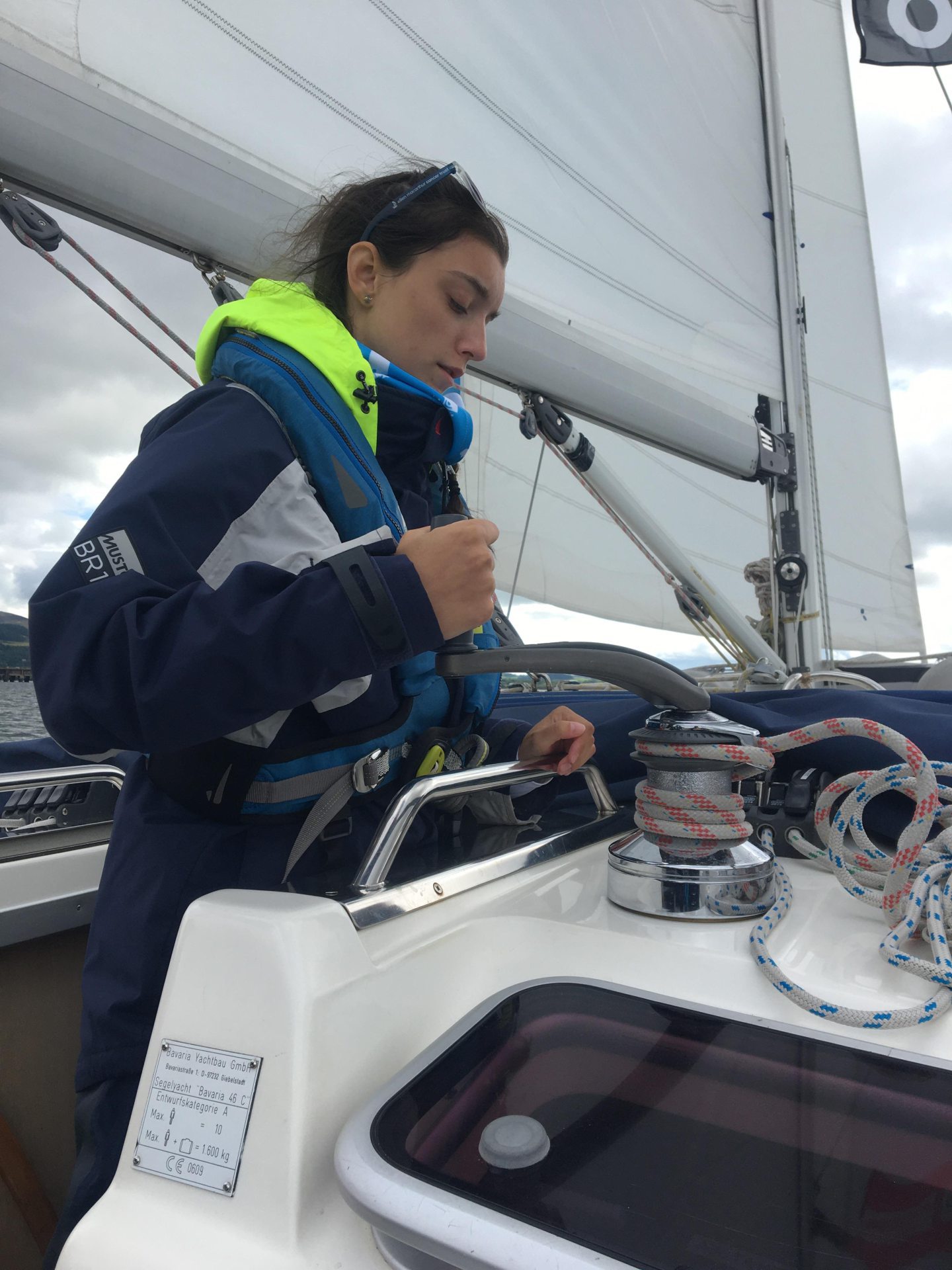

Jovi is one of the almost 250 young cancer and blood disease patients who will sail out of Largs this summer, part of an adventure organised by the Ellen MacArthur Cancer Trust, the charity founded by the yachtswoman who in 2005 broke the world record for the fastest solo circumnavigation of the globe.

It is a unique experience — on a fleet of sail boats up to 44 feet in length the crew spend almost a week at sea, zipping around the islands and living onboard.

For Jovi, it is the second year she’s taken part.

It meant reconnecting with friends she made on the last trip, and making a few more along the way.

But once again it allowed her to spend valuable time with people who have gone through similar experiences to her.

“There is a feeling of relief that it doesn’t matter bringing it up, because everybody understands,” she says. “There’s no issue going into the deep, dark details, because everybody has those deep, dark details.”

Banchory student’s late-night call and blood disorder diagnosis

Jovi’s own diagnosis came when she was just 17. A keen gymnast and trampolinist, Jovi was feeling tired a lot. Friends at Banchory Academy started telling her she looked skinny and pale.

Her mum took her to get a blood test thinking she might be anemic. The test was in the afternoon but just a few hours later, at 11pm, the phone rang. Jovi had to go to hospital the next day.

Was she scared?

“I didn’t sleep well that night,” she says with a wry laugh. She was told her haemoglobins were low but she didn’t know what that meant. Doctors took more blood and did a painful bone marrow biopsy.

A week later, she was diagnosed with something called paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. A doctor said that without treatment, she could expect to live for another five years.

“So that was scary,” says Jovi, who was also told that the treatment was an intravenous injection into her hand every two weeks.

“That was the surreal moment of, no, this can’t be happening to me. I came here to be fixed, and you’re not fixing me.”

Life plans suddenly under threat

Her diagnosis came when Jovi’s life was about to hit top gear.

She’d already been accepted to study archeology at Aberdeen University, and friends were making plans for gap years, summer trips and all the other exciting things that happen to teens making the jump into adulthood.

Suddenly, all of that seemed to have been taken from her.

“Part of me was very much in denial for a long time,” she says. “It was hard at school, because everybody else was living normal lives.

“I mean, I didn’t get to go on a girls’ holiday, and I spent a lot of my last few months of school either not there or kind of just dipping in and out. Everything was different for me, and it wasn’t how I imagined that transition.”

Isolated in the ICU during Covid

Jovi started her treatment, and also her studies in Aberdeen, but it wasn’t easy.

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, often shortened to PNH, is extremely rare – just five people in a million have it, according to charity PNH Scotland.

It is a chronic and life-threatening blood disorder that causes the destruction of oxygen-carrying red blood cells, usually leading to anaemia.

Jovi suffered bouts of extreme fatigue that left her unable to think clearly. At university, she was often unable to read or write and everything seemed to take her longer to complete than everyone else.

Then, because of the medication she was taking, she contracted meningococcal sepsis, a bacterial form of meningitis.

She eventually suffered an extremely dangerous septic shock, a dramatic drop in blood pressure that only three or four people out of 10 survive.

What made everything worse was Jovi’s timing. It was summer 2020 – the height of the Covid pandemic — and the ICUs were full of severely ill Covid patients.

Jovi was put in a separate ICU with non-Covid patients but the protocols at the time meant she could have no contact with her family. Her only means of communicating with them was Facetiming them on her phone.

Even the hospital staff were distanced from her, clad in protective masks and scrubs, faces barely visible.

The Covid rules meant staff had to change their scrubs every time they went into a different ward. Fed up of doing this, doctors and nurses that needed to speak to Jovi resorted to simply writing a message on a bit of paper and holding it up against the window.

New medication that turned Jovi’s life around

Today, Jovi is on a new medication that is more efficient and has improved her symptoms.

“It’s amazing to be honest. I’m so grateful for it. I’m living a bit more of a normal life now.”

That life includes studying for a PhD in archeology at Aberdeen University, and her by now almost regular summer sailing trips.

After loving the adventure last year she couldn’t wait to do it again, the excitement building until the moment she stepped back aboard.

“It felt like coming home,” she says. “I knew from experience what an amazing week it was going to be. And I just couldn’t wait to get started.”

It also gave her lots of new photos for her Instagram page, where she charts her life with PNH.

The page has another use — helping other young people living through their own PNH diagnoses.

And every time someone gets in touch to thank Jovi for talking about it, she’s reminded that those life moments she missed out on because of her condition haven’t all been in vain.

“If I had the chance to take away the experiences I’ve had with my health over the last eight years, I wouldn’t take it away,” she says.

“It’s horrible at the time, but it’s made me who I am.”

Conversation