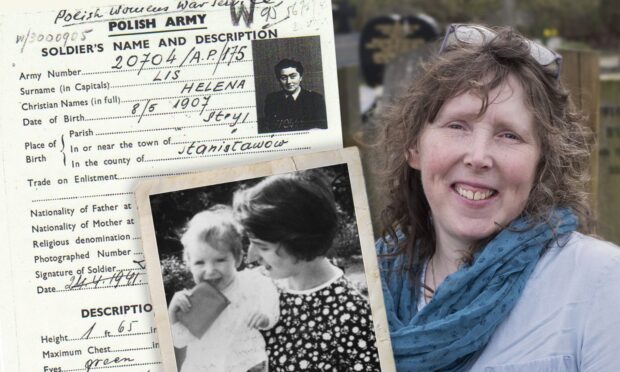

Jennie Workman Milne always knew her mother Elizabeth’s life was cloaked in mystery.

It was no secret that she had been abandoned as a baby in Devon during World War Two and brought up by a sympathetic and loving spinster nurse.

Her birth certificate gave her surname as Lis, but this was later changed to Lister to make her sound ‘less foreign’.

Elizabeth called herself a Russian-Polish Jew, and would reveal some details of her background, although as a child Jennie didn’t know how the information had been obtained.

Even as a child, Elizabeth was difficult and tempestuous, testing the limits of the nurse who brought her up, Rose Toms.

Jennie says Liz, as she was known, had a fiery nature, and was rebellious and out of control as a teenager. By all accounts, it was clear she needed help.

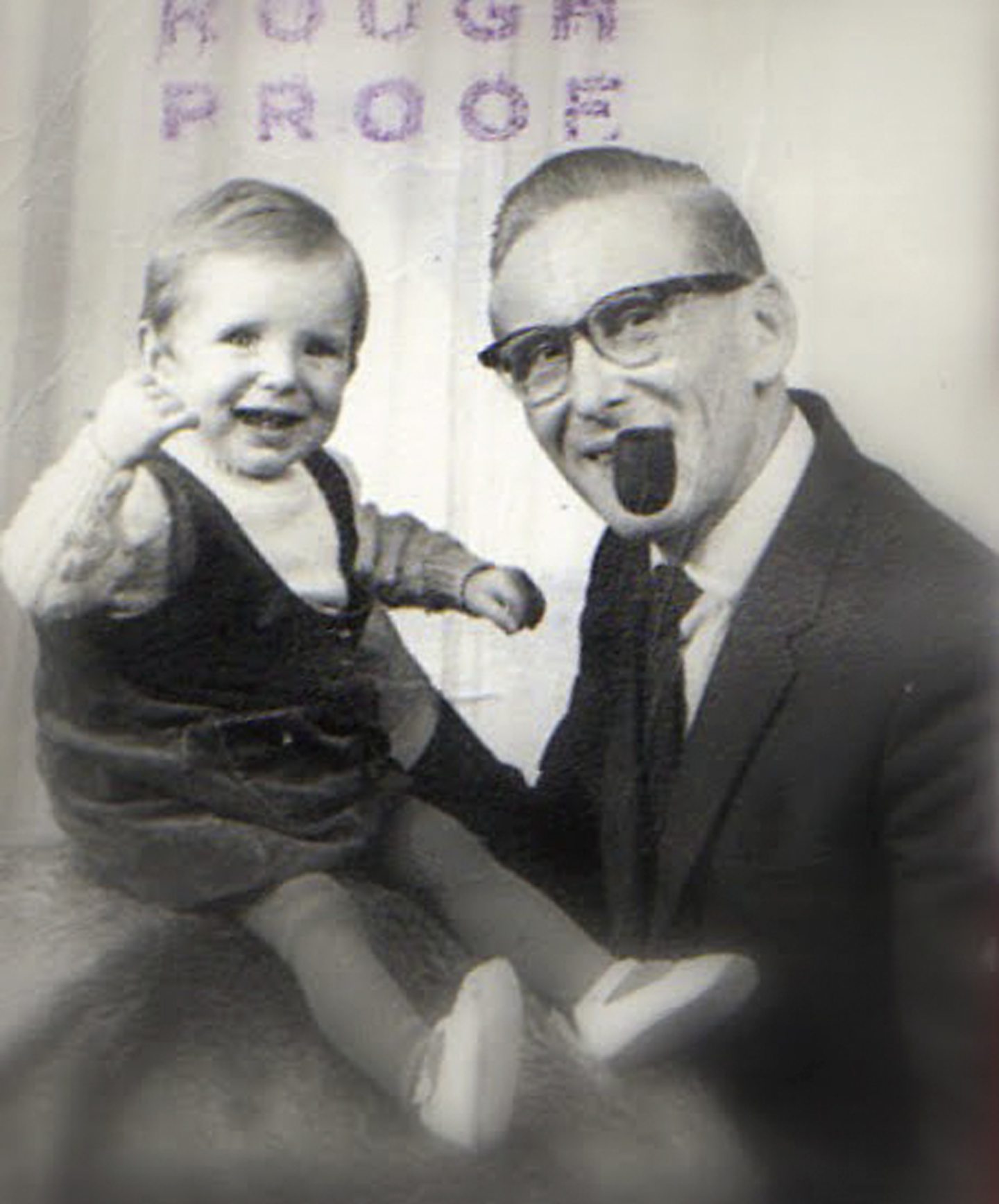

In her early 20s Liz had an affair with a much older man, Derek Workman – the father of Jennie and four of her siblings.

Jennie thinks Liz was deeply affected by the lack of her own father.

Adulthood and motherhood did nothing to calm Elizabeth’s tormented soul.

Jennie, 57, says: “She was a school teacher, very articulate and attractive. But behind closed doors she was abusive.

“She was violent. She beat us up, she beat Dad up.”

Eventually Liz left Derek, Jennie and two of her siblings to live with a boyfriend, who later became Jennie’s stepfather.

Sudden death of Jennie’s father

Meanwhile, Jennie’s beloved father died suddenly when she was 10, a loss that she feels to this day.

Her mother cut off all ties with his family shortly after he died.

Jennie and her siblings returned to live with her mother.

The abuse then escalated and became very dark, Jennie says, “calculated and sadistic.”

Whereas her father had tried to protect his children, the stepfather was dishonest, and orchestrated situations to get Jennie and her siblings into trouble.

The couple thought nothing of beating the children with a dog chain or other implements over a perceived misdemeanour.

A friend of Jennie’s later said hers was one of the worst cases of abuse she’d ever come across.

Liz married four more times

Liz married four more times after the death of her father, changing her children’s names every time.

“We didn’t know whether we were up or down,” Jennie says.

“We knew Mum’s Jewish background was very important to her, but she said that she didn’t know who she was.

“She was always searching for a sense of identity, but almost afraid to find out the truth.

“She was unable to watch Schindler’s list for example as she said ‘That’s what happened to my family’.

“This narrative was the background to my childhood.

“Mum would always tell me that her uncle had been killed by the Gestapo and her nephew had escaped to America after being badly beaten by the Germans at 14.

“I grew up knowing those things, but with no real context or understanding of who she really was.”

Jennie left school at 15 and ran away from home at 17.

Although she was keen to escape her abusive surroundings, Jennie still loved her mother, and it was that love which kept their relationship together to the very end.

Jennie became a Christian, married Brian Milne in 1988 and they have nine children, and four grandchildren.

She studied photography at Robert Gordon University and now helps run RGU’s photography department.

In the busy years when the children were young, Jennie’s feet barely touched the ground, let alone having enough time to think about her mother’s disturbed roots.

But in the back of her mind were many questions, and a desire to help her troubled mum.

Jennie made an attempt to learn more about her mother’s background in 1999, and learned that Elizabeth had in fact met both her parents in the 1960’s.

They were divorced and both remarried.

“Mum told me it was her father’s second wife who had said her birthmother was half Jewish, as she had known her in Poland, but mum was unsure it was true.

“She told me ‘Jen, my birthmother told me she had falsified my birth certificate – I don’t even know if my birthday is correct, and I have no proof I am Jewish.’

Liz eventually met her parents

Liz met her mother in a café, but found it the experience challenging.

Jennie said: “Mum couldn’t do it again, she found it overwhelming.

“Her parents were very badly affected by the war, although her mother told my mum she had never stopped looking for her.

“Mum later told me she regretted losing contact with them and tried to find them again.”

Liz’s father died not long after the meeting.

It wasn’t until 2012 when her youngest daughter Faith had a World War Two project at school however that things started to move on tracking down Liz’s roots.

Jennie asked Liz to write down every single thing she could remember.

But shortly after this, Liz was diagnosed with cancer and became very sick, very quickly.

She died in 2014.

Liz’s life was a mystery and Jennie knew she had to get to the bottom of it

Jennie said: “As I stood at mothers funeral by the coffin, I realised I didn’t know the woman inside.

“In many ways she’d shaped my life for better, for worse, and I knew her very, very well, but she was a mystery, she kept secrets, but she had secrets kept from her.”

A couple of months later Jennie woke up with an inner conviction.

“I knew I had to find out what had happened, and who my grandparents were. I took the fragments my mother had written and every single tiny detail she had about them.

“But there was no starting point. I didn’t even know if her name was correct.”

Tracking down Liz’s father was easier.

Stanislaw Lis turned out to have been a representative of the Polish president in exile after the war.

As a highly decorated Polish officer he was held in high regard for his bravery during the war, but as a political refugee he was unable to return to Poland.

He is buried in Gunnersbury Cemetery in Kensington.

In the quest to find out who Liz really was, Jennie left no stone unturned.

She joined every Polish group and forum to try and make connections with people who might be able to help.

She even turned to the TV programme Who Do You Think You Are? who initially said they couldn’t help her.

In a lucky break, Glasgow-based Jewish genealogy expert Michael Tobias, a consultant on the programme, saw Jennie’s plea and stepped in to help her.

The mystery started to unravel, as Michael quickly found the records for Jennie’s grandparents and great-grandparents.

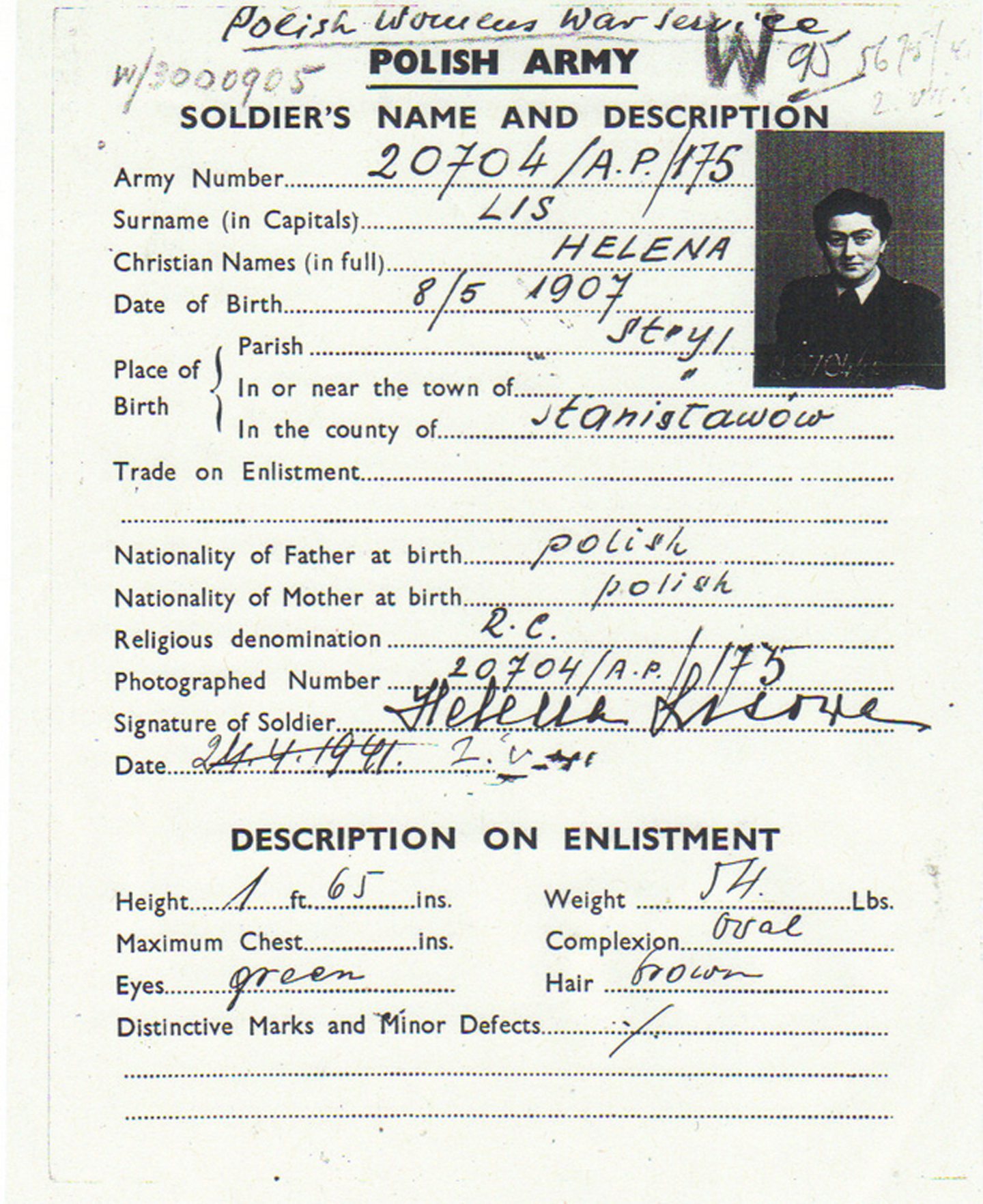

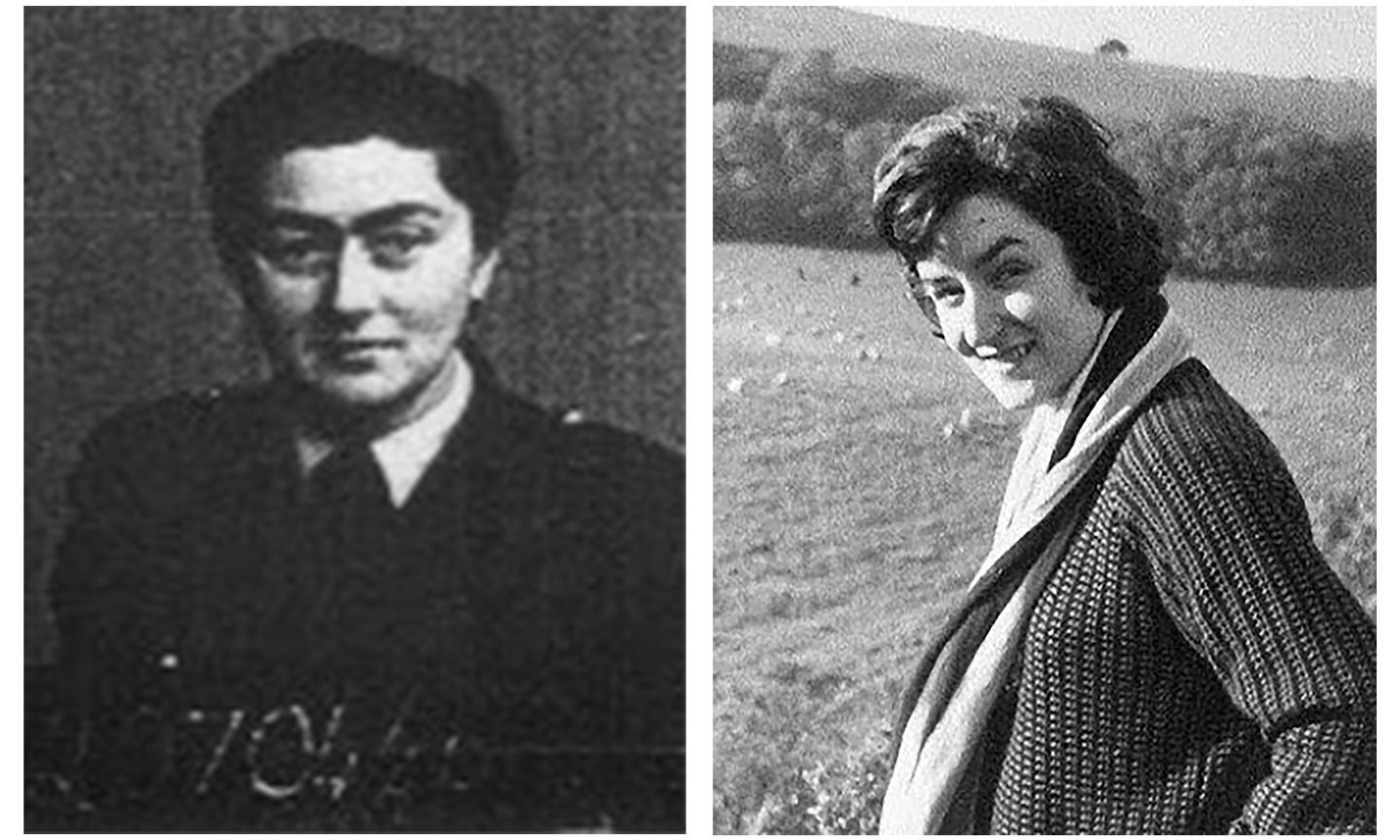

Jennie said: “When my grandparents’ military records came through front door it was the first time ever seen an image of my grandmother, a tiny image on an identity card.

“I knew immediately that she was my mother’s mother, I could just see it in her face.

“This taken was during World War Two she was in the Polish Army and the document said she was Catholic, she really tried to prove the point by calling herself Helena Teresa Maria Anna and a made-up Polish name.

“I thought she overdid it a little bit, and it gave away little about herself.”

But Jennie’s grandfather Stanislaw Lis’ records began to crack the mystery wide open by identifying Helena’s family as Rothenbergs.

From there, Jennie found out that Helena, Liz’s mum, also had a sister, Irena, who stayed in Poland and worked with the Resistance.

Many changes of name and age

Both women had changed their names and ages, making them difficult to trace.

Irena, a countess, was arrested with her only son James in Warsaw for hiding a small starving Jewish boy who had escaped the ghetto.

James, who was 12, was interned in a concentration camp, whilst Irena also spent time in a camp and was put on a death march to Dachau.

She escaped and reunited with James, who had also survived, in Vienna and both went to the States after the war.

A branch of her descendants has subsequently opened up to Jennie in the United States, giving her enormous emotional pleasure and comfort.

James’s daughters knew Liz’s mother but said she had never revealed that she had a daughter.

All Liz’s children were traumatised by her pain

Jennie admits frankly that all her mother’s seven children were traumatised by Liz’s personal trauma, and working through its effects took a very long time.

It remains an ongoing process.

Liz died before Jennie found out, and continues to find out, so much about her family.

But she takes comfort from the “real connection” she managed eventually to establish with her mother just before her death.

She went to see her in Honiton, Devon where she was living and had been a well-known local councillor.

“She was very weak and hoarse, but we had an honest conversation.

“She then called me to go and get my camera as there were pheasants at the end of the garden.

“Her way of saying she loved me”

“She’d always encouraged my photography, and I knew this was her way of saying she loved me.

“I have this photo framed in my bedroom. I was the last of her children she contacted by phone a few days before she passed away.

“She couldn’t speak really but neither of us wanted to put the phone down.

“We had finally connected.”

Jennie’s describes the long journey towards understanding her mother as “the best thing, on a personal level, that I’ve ever done.

“What I discovered expanded my world, made me more confident, and has given me a sense of wholeness and the realisation that we are all connected to the people who have made decisions before us.

The journey has help Jennie understand her mum

“It’s helped me understand my mum’s sense of displacement and that family is important, where you come from is important.

“I never wanted to be seen as a victim, yet I carried pain deep inside.

“Visiting the Aberdeen shul, I learned that the whole Jewish community carries trauma, it took the focus away from me.

“I’m thankful for my parents and wouldn’t change them.

“And I’ve been able to move forward and embrace life.”

Conversation