Caring for patients in their final days and hours of life, two Inverness nurses dreamed of a better way to look after those with life-shortening illnesses.

That was in 1983. Four decades later, the ongoing legacy of Flora MacKay and Cecilia Bottomley lives on through the world-class work of the Highland Hospice.

But what does a hospice do? What does it look like inside? And is a place so associated with dying, a sad place to be?

Press and Journal Obituaries writer Lindsay Bruce went along to meet families, staff and volunteers at the specialist Inverness centre, and in doing so discovered one of Scotland’s best-kept secrets.

Surprising first impressions

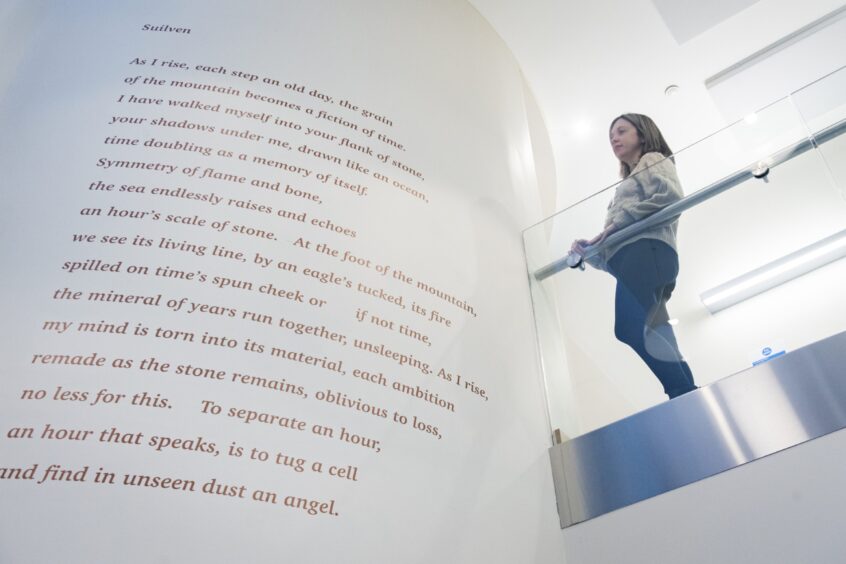

It’s hard to imagine a place with a more paradoxical first impression than that of Highland Hospice.

On the one hand, I’m aware my walk alongside the fast-flowing Ness will lead me to a place where so many of the people I’ve paid tribute to spent their final moments on earth.

On paper, it should be somewhere solemn.

On the other, on entering the doors of the centre – a hybrid space where modern, light, architecture melds with an historic ‘big house’ (once the property of the Highland Health Board), there’s an immediate sense of serenity, warmth and – dare I say it – maybe even joy.

‘I wanted to give back. The Hospice helped my Bruce,’ says Alice

“I just love it here in the coffee shop,” Alice Gordon tells me. She’s one of 900 people volunteering with the charity. “I’m made to feel very much part of the hospice family, and It’s my way of giving something back.”

Alice’s husband Bruce was diagnosed with cancer 10 years ago. When it came back “with a vengeance” they received specialist support from Macmillan and Marie Curie. When Bruce’s illness progressed further she turned to the Highland Hospice wellbeing team, then later made use of what would become the pioneering palliative care helpline.

Launched in May 2023 the 24/7 service offers advice, support and information for patients nearing the end of life, or their families, carers and professionals. It covers the whole of the Highlands, Argyll and Bute. During 2023/24 1,300 people used the phone line.

“It was lovely to have a knowledgeable and reassuring voice at the end of the phone,” Alice said.

“Bruce never once complained, but having someone there to help me help him was such a help.

“I knew when he passed away that I would do whatever I could to support places like this. I’ve even ziplined off the Kessock Bridge!”

‘We’re so proud of our helpline,’ says CEO Kenny

“It’s run by specialist nurses who can help in myriad ways to support families. We’re really proud of the palliative care helpline,” says Kenny Steele, Highland Hospice CEO since 2011.

So he should be. At a time when our hospitals are at crisis point analysis by the NHS Highland Public Health Intelligence unit showed people who used the helpline spent on average six fewer days in hospital in their last year of life.

“And for the people who accessed our Palliative Care Response Service – which we launched in 2022 – they spent on average 20 fewer days in hospital in their last year of life.”

The statistics blow me away.

“Does every hospice offer such services?” I ask.

“No, I think we’re the first in Scotland to launch a helpline like this,” Kenny adds.

It won’t be the only time during my visit where I’m taken aback by the scope of the services on offer.

“We operate a partnership approach, which I’d like to develop further. A disjointed service benefits no one. At the moment Amazon knows more about your likes, needs and preferences than the hospital if you turn up.

“We’re working on a way – funding permitting – to create a digital profile so every person involved in someone’s care can access information quickly and in a way that minimises stress.”

Dedicated ‘lifeline’ reduces need for ambulances

The reality is that there can be countless “partners” involved in a person’s care.

Susan Maclennan, a former district nurse with Marie Curie, works on the palliative care helpline.

“Calls can vary – a lot of the time relating to pain,” she explained.

“We can arrange for a change of medication, for example. We do a lot of signposting and connecting people to the help they need.”

One of her calls was from a lady on holiday who took a sudden decline, quickly moving into “end of life” care.

“We helped her register with a local GP. We contacted district nurses. If we have consent we can refer on to other services too, such as befriending.

“In one case we were able to organise the right help to enable a patient to stay at home rather than wait hours for an ambulance, then endure another long wait outside a hospital in the ambulance.

“It really is a lifeline.”

Bereavement service helped dad Will speak to his family

Will Macrae knows only too well how valuable a Highland Hospice lifeline can be.

After losing both his parents he came to bereavement counselling before volunteering for the charity. He’s now the hospice’s digital fundraiser.

In 2014 Will signed up for the Strictly Inverness fundraiser. He thinks the busyness of life masked his grief.

“Learning to dance and meeting new people was amazing. Really full on.

“But after that, my wife suggested I should think about the bereavement service. I was just really snappy. Little things would get to me. I’d lost both parents but had kept myself so busy.

“It really helped to give me the skills to come home and talk about things, instead of keeping everything to myself.

“It helped the whole family, because of that. I hadn’t realised how much the losses were affecting my kids.”

Grief team support Highland youngsters after loss

Of course, grief absolutely affects children.

Louise Mainland and Craig Mitchell are part of the Crocus team, offering specialist bereavement counselling to children aged five-18.

“To say ‘losing a loved one’ doesn’t cover it,” says Craig. “Sometimes it’s a teacher that’s been a really valuable, protective role model. Grief is complex.”

Offering leisure-based groups, one-to-one and group counselling, they’ve even got a small cohort of young adults who now serve as Crocus volunteers, using their own experiences to help others.

“They really connect with them, and there’s a nice amount of lovely dark humour, that they fully get, because they’ve walked that path too.”

‘We can become ‘stuck’ in grief. We can help,’ Louise says

Louise believes peer support is invaluable.

“We can often – wrongly – think someone needs fixing, but actually all they need is to be seen and heard.

“We also support people to have difficult conversations.”

Louise says they receive a large amount of referrals as a result of a traumatic death or suicide. The most likely type of grief for people to become “stuck” in.

“There are a lot of whys and unanswered questions with suicide. Especially if children are grieving. It’s very common for children not to be told what happened – and then later find out.

“We help facilitate honest, age-appropriate conversations. When it comes to grief and bereavement, if the parent is struggling, the child is struggling.

“Death happens to everyone, and everyone will experience grief. But we’re still not great at being able to talk about it,” added Louise.

‘It’s a privilege to deliver ‘Last Aid’ training’, says Will

Facing up to the reality of death and dying is something Will has now embraced.

“I’m what we call a ‘Last Aid’ trainer.

“As opposed to First Aid, this course helps people prepare for death. It helps with accepting what will happen, what it will look like… We cover things like power of attorney too.

“It’s really helpful, and for me it’s a privilege to help people in this way.”

Knowing what lay ahead for him, Glasgow-born Jimmy Neil expressed a desire not to be taken to hospital.

The 87-year-old retired welder was supported by Sunflower Home Care – offering tailored help and care to people in remote and rural areas in the Highlands – to help him remain at home.

Lorna Devlin, Jimmy’s daughter, is grateful for the help her dad received.

“He was this big strong man. He loved motorbikes and pipe music. It was so hard to see him become weaker.

“The Sunflower team offered my dad dignity.”

‘In-patient unit is a far cry from standard hospital wards’

For others, however, final life care may best be provided in the hospice 11-bed in-patient unit.

Senior nurse Gillian McRobie showed me around.

What struck me first was the smell – or lack of it. There was nothing hospital-like about this spacious, serene space, except perhaps for some nurses in scrubs.

Neither was there the constant white noise of monitors or nurse-call buzzers.

“We try to keep it as calm as possible for the people staying with us,” Gillian explains.

She shows me where wires, oxygen tanks and masks are kept in each room. Not on display, but accessible when needed. There are also flat screen TVs and stunning river views.

It’s a far cry from the crowded, curtained-off cubicle in a shared ward where my father passed away in hospital.

As we chat a chef does the rounds, popping into each of the en-suite rooms.

“Some people are here and then go home. Others will be with us for that final stage of life,” the former Marie Curie nurse explains. “We also have people come to stay for a week – such as those with MND or MS – to have physio. We have a dedicated space for that too.”

There are also beautiful side rooms for family members and visitors. A space that’s been used to conduct weddings in the past.

‘People’s hospice’ for the people – sustained by the people

The current unit – which was an extension of the hospice’s original offering – opened in 2016, and is staffed by nurses, clinical nurse specialists, health care assistants, and GPs on rotation.

But despite offering such a needed service, the hospice remains reliant on its community for funding.

Covering a population of over 230,000 people scattered across an area almost the size of Belgium, the NHS annual grant of just over £2million covers only about a fifth of its costs. A shortfall of just over £8,500 a day remains.

“Every member of the team here is very aware that we are so privileged to work in this environment, doing what we do. I can’t image a more fulfilling nursing role than ensuring someone’s final chapter of life is as good as it can be.”

‘People deserve the best possible care, that’s why we’re here’

As I leave the hospice to catch my train – I stop in at one of the city’s many Highland Hospice charity shops. CEO Kenny Steele’s words have stuck with me.

“About 2,800 people die in our area every year. Around 80% of these deaths are people with palliative and end-of-life care needs.

“We believe these people should have access to the best quality care and support to make the most of their limited time. And all deaths impact loved ones, and in some cases, people dealing with grief can benefit from additional support.

“This is who Highland Hospice is for.”

Conversation