The last time Chris Thomson ran a marathon, he ended up in the back of an ambulance.

A Type 1 diabetic, the Peterhead runner is used to dealing with insulin spikes. But on that occasion, about halfway through the Edinburgh marathon, reality intervened.

“I didn’t even realise my blood sugar was dropping,” Chris, 35, recalls. “A medic spotted it, grabbed me and put me in the ambulance.”

It was a frightening moment. And yet, next weekend, on Sunday April 27, Chris will be lining up at the start of the London marathon.

Why?

This year marks exactly 30 years since Chris was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes — at the age of just five years old. He’s using the event as a way to celebrate just how far he’s come.

“I’ve done marathons, I’ve done ultramarathons, I’ve climbed Kilimanjaro, but this is the one that feels the most personal,” he says. “It’s 30 years to the week since I was diagnosed, so I thought, right, if I’m going to mark it, this is the one.”

The 200 decisions a day Chris makes to manage diabetes

Unlike Type 2 diabetes, which is often associated with lifestyle factors and can sometimes be reversed, Type 1 is an autoimmune condition with no known cause and no cure.

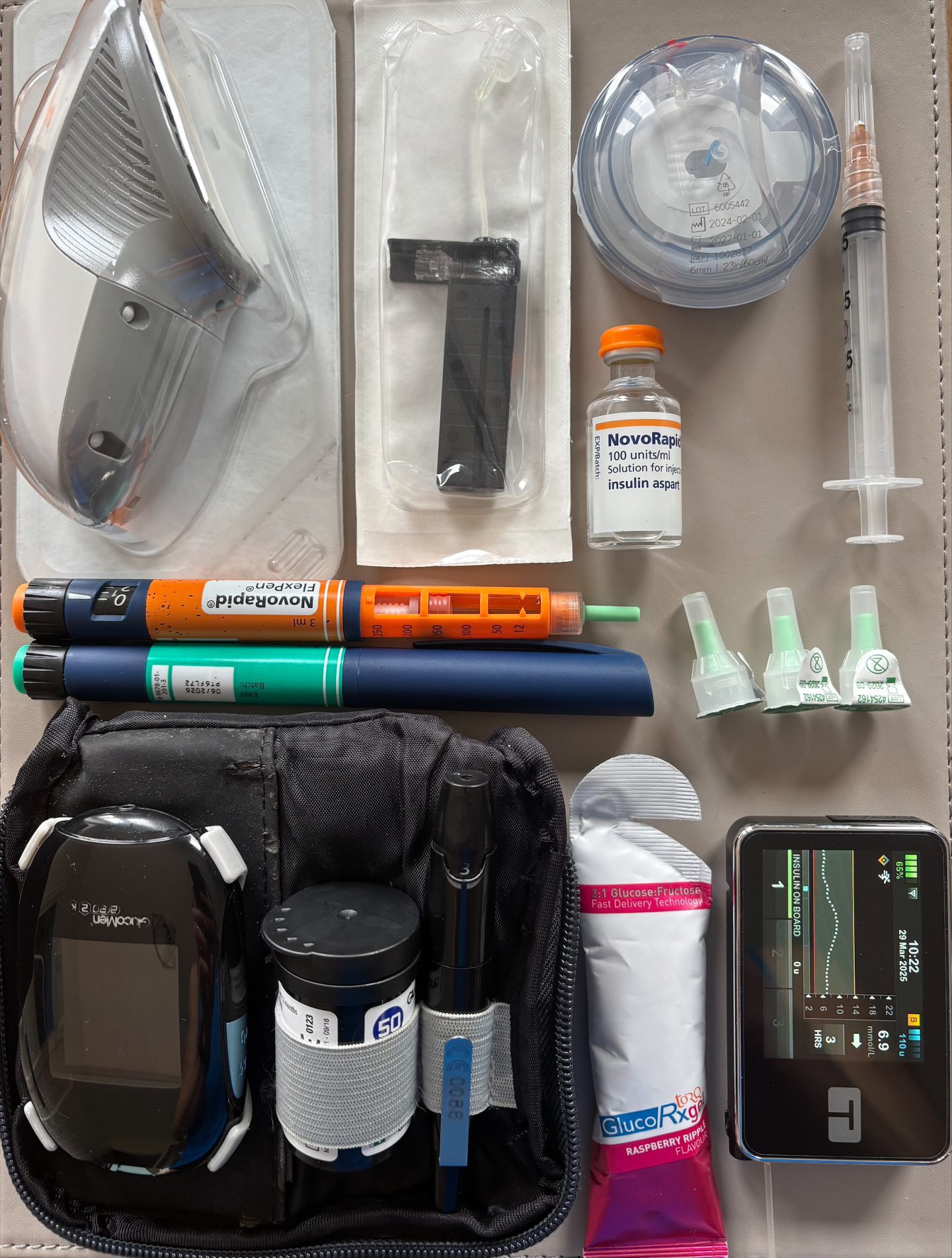

It requires constant management — insulin injections or pumps, blood sugar monitoring, and a never-ending stream of tiny decisions most people never have to think about.

“They say people with Type 1 make 200 extra decisions a day,” says Chris, who works for oil and gas company Score in Peterhead.

“And it’s true. Everything from going for a run to walking into a meeting at work — you’re always having to think about it. It’s invisible, but it never goes away.”

For Chris, keeping his blood sugar stable during marathon training is a constant balancing act.

If his glucose levels drop too low and aren’t corrected quickly, he could fall unconscious or even slip into a coma.

During the Edinburgh marathon, despite careful planning, a sudden drop in blood glucose left him confused, disoriented and eventually in the back of an ambulance. He got back out and finished — but only just.

“Even with all the training in the world, Type 1 diabetes is always there,” he says. “You can do everything right, and something can still go wrong.”

What Chris Thomson needs to do to run London marathon

This time, though, Chris has a new ally — technology. Just weeks ago, he switched to an insulin pump, a device that delivers insulin automatically and works in tandem with a continuous glucose monitor to keep his levels more stable.

“It does a little bit of the thinking for you, which is a game-changer,” he says. “I’ve been testing it on my longer runs and it’s giving me a lot more confidence. I feel safer going into this one.”

But even with the tech, preparation is everything. Chris has trained hard, refined his fuelling strategy and knows he’ll need to keep a close eye on his glucose throughout the race. Jelly babies are stashed and ready.

“You’re always carrying sugar, always checking your levels. It never stops. But that’s just the reality of it. You deal with it and you keep going.”

What Chris learned about insulin when he climbed Kilimanjaro

If training for a marathon with Type 1 diabetes is difficult, climbing a mountain with it is something else entirely.

In 2023, Chris summited Kilimanjaro — the highest peak in Africa — but not without a whole new set of obstacles thrown at him by his condition.

As he gained altitude, he discovered that even insulin behaves differently in thin air.

“I realised pretty quickly that insulin doesn’t work the same once you get above 3,000 metres,” he says.

“I was taking injections and thinking, ‘This isn’t doing anything.’ But the danger is, if you take too much and your blood sugar crashes, you’re in serious trouble — and you’re miles away from a hospital.”

It wasn’t just the altitude messing with his body. The cold, too, posed a threat.

“On the first night in the tent, I woke up and everything was freezing — literally. And I panicked, because insulin can’t freeze. If it does, it’s useless. I was stuffing it down my t-shirt, into my waistband, anywhere warm, just trying to keep it from being ruined.”

Despite the extreme conditions and uncertainty, Chris made it to the summit — and learned a lot in the process.

“I’ll be more prepared next time,” he says, casually mentioning that he plans to tackle Mera Peak in Nepal next year — a mountain higher than Kilimanjaro, with a view of Everest from the top.

“I wouldn’t want anyone to think you can’t do it because you’ve got Type 1 diabetes,” he says.

Chris’s hidden condition, and his reasons for speaking out

For most of his life, Chris kept his condition relatively private.

He didn’t want to be treated differently or seen through the lens of his diagnosis. But with the 30-year milestone approaching — and with the opportunity to share his story — he’s decided it’s time to speak up.

“I’m not usually big on telling people about my diabetes,” he says. “But I feel like this is the right time. If it helps raise awareness or makes one person feel like they can do more than they thought, then it’s worth it.”

Chris is using the marathon to raise funds for Breakthrough T1D, a charity focused on finding a cure.

“There are other brilliant organisations that help people live with the condition,” he says. “But Breakthrough T1D is really focused on the end goal — curing it. And they’re getting closer. But the closer they get, the more support they need.”

The fundraising target is £2,000, but Chris is already well on his way, and hopes the story behind his run will inspire people to dig deep.

“I wouldn’t want anyone to think you can’t do it because you’ve got Type 1 diabetes,” he says. “It’s about proving to myself it can be done. I’ve had it for 30 years, and I just want to show that it doesn’t have to hold you back.”

This time, Chris isn’t planning on seeing the inside of an ambulance. He’s aiming for something far more satisfying.

Crossing the finish line, on his own terms, 30 years after Type 1 diabetes tried to write the rules.

Click here to donate to Chris Thomson’s London marathon fundraiser.

Conversation