Scots law gives certain family members fixed entitlements in your estate when you die. These are called ‘legal rights’ – viewed by some as justified because they protect against ‘disinheritance’, and by others as a restraint on freedom to pass your assets to who you want.

The important question is whether these legal rights would affect your plans? Legal rights are generally limited to certain people – a surviving spouse or civil partner and children (or grandchildren where a child has died before their parent). They do not apply to partners and they do not apply to step-children. As the law stands, legal rights are calculated as a proportion of what is called your ‘moveable estate’ – broadly this excludes the value of land and buildings, although future changes in the law in this area may remove this distinction. The proportion depends on who has survived.

If survived by:

- a spouse/civil partner but no children – the spouse/civil partner is entitled to half of the moveable estate.

- children but no spouse/civil partner – the children are entitled to half of the moveable estate, split equally among them.

- a spouse/civil partner and children – the spouse/civil partner is entitled to a third of the net moveable estate and the children are entitled to a third of the net moveable estate, split equally among them.

If a spouse/civil partner or child takes their legal rights they cannot also benefit from the provisions of the will – it’s one or the other. In practice, most people who are entitled to legal rights decide not to enforce them, either because they wish to respect the deceased person’s wishes or because the provisions left for them in the will have a greater value anyway. However, legal rights are problematic if you wish to leave most of the value of your estate to one or a small number of the family, with the others getting less or nothing at all. This might arise where a business owner wants to leave the business interest to one of his children – the other children may not inherit under the will but they may have a very large legal rights entitlement.

Also, estranged children or separated spouses/civil partners might not get a mention in the will but they do have legal rights entitlements. If legal rights might frustrate your succession plans, then it is important to think ahead. There are a number of techniques to mitigate or eliminate the extent of the entitlement.

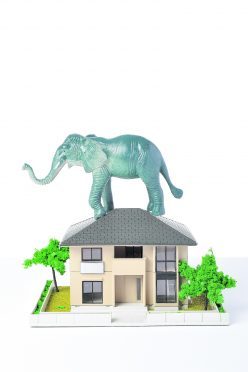

While most of us plan to leave our estate to our own kith and kin, a major risk to many people’s succession planning is the spectre of inheritance tax (IHT).

This time it is HM Revenue & Customs, rather than family members, that wants a slice of your estate. At 40% of the value of assets, when it hits, IHT can strike hard. Working out whether your estate may be subject to IHT requires a clear picture of the total extent of the estate, what it consists of and who you want to leave it to. IHT is sometimes referred to as a voluntary tax – that’s a reference to the variety of reliefs, exemptions and planning that can be employed during a lifetime, and immediately after a person’s death, to mitigate, or at least defer, the tax.

There are four main methods to mitigate the exposure. Firstly, ‘lifetime giving’ involves gifting assets to your chosen heirs now, rather than after death. In most cases, so long as you live for seven years after the gift, IHT will not apply, although it is important that once the asset has been given away that the donor no longer receives any benefit from it.

Secondly, where our wealth takes the form of certain assets that have relief from IHT (e.g. many business and farming interests) the value can be said to be ‘sheltered’ from IHT – for that reason, some people consider investing in these type of assets to secure that shelter.

Thirdly, certain financial products provide a means of investment and also an inheritance tax upside.

The use of life assurance is the fourth traditional method. It is always important to consider, with the benefit of independent financial advice, the broader implications of any investment strategy. What suits you best will depend on your personal circumstances and objectives.

Another risk for many people who have worked hard over their lifetimes to buy their own home, is that it might be lost to pay for residential care in later years. Faced with this prospect, many people consider what they might be able to do to mitigate this risk.

The law in this area is complex with detailed rules to prevent people deliberately ‘depriving’ themselves of assets with a view to avoid future residential care home costs.

Also consider putting a power of attorney in place. The use and effect of powers of attorney is now much more widely recognised. Acknowledging that a day may come when we can no longer make decisions for ourselves, whether because of some unanticipated and nasty accident or disease or should dementia become a factor in later years, it is a sensible precaution to consider appointing someone to make decisions for us through a document known as a power of attorney. In this way, we are in control of who makes the decisions – whether this is a spouse, or one or more children, or others. The powers that can be included are extensive, ranging from financial matters to personal welfare. Where a person becomes incapable and there is no power of attorney in place, then it may be necessary for someone to seek to be appointed by a Court as guardian – which may be a costly and time-consuming process.

- Mark Stewart is a partner in the personal & family team at Brodies LLP. For more information, contact Mark on 01224 392282 or at mark.stewart@brodies.com