Everyone knows the lily, with its glossy white trumpets, alluring scent and annoying habit of getting fluorescent orange pollen on your white shirt at weddings. But there are literally thousands of species and varieties in all manner of shapes, sizes and colours – and more are being added all the time – some of which come about in the most unlikely ways

But before we get started properly, I just wanted to catch your attention and show off a bit.

But back to the matter in hand, the genus Lilium in all its glory. That’s lilies to you and me.

What to you get if you cross (and I mean that literally in the horticultural sense) this …

… with this?

Well, you get the biggest breakthrough in lily breeding for years.

This gem was introduced with much sensation to the public at the Chelsea Flower Show in 2011. I defy you to describe that colouring.

While traditional hybridisation would involve keen Victorians daubing pollen from one species in a genus to the stigma (that’s the yellow thing sticking out of the middle of the blooms above) of another, randomly hoping for a new flower colour or form, things have moved on so far in recent years that all manner of DNA tweaking can be done under lab conditions to achieve results the gentlemen (and women) of old could only dream of as they pottered about in the conservatory.

Here’s the science bit, just skip it unless you have a PhD in biochemistry … This cross was made possible in the lab using a technique called embryo rescue. The little seed embryo from the cross is removed from the seed capsule itself and then is grown on in a test tube agar solution as the seed does not contain enough endosperm to nourish the emerging embryo to the cotyledon (first leaf) stage. Didn’t understand that bit? I didn’t really either. Let’s just leave them to it.

Welcome back. Last time I promised you more lilies so here are a few I’ve been growing this year:

Another of my own efforts is Lilium canadense (see how one can often get a clue as to the origin of a species from its name) which I’m afraid is for the bin as it has become infected with a virus. This is a surprise as it came from one of my favourite and very reputable suppliers but it must go before it infects other lilies and possibly even their relatives, such as Fritillia (more of which later).

I gave you a sneak peak of Lilium taliense last time but here it is again, seeing as how it is a such a stunner.

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of lily species all over the Northern Hemisphere, with the majority crowded round South-East Asia but North America and Canada are well represented and there are even a few native to Europe, although over-development of land and grazing are a constant threat. There is a single representative in the Southern Hemisphere, L. philippense. If you can’t guess where that lives, you’re not going to be much use on Pointless.

There is even – arguably – a species native to the UK. Lilium pyrenaicum is, presumably, to be found in the Pyrenees (my schoolboy Latin stretches that far although I got a C so don’t trust anything I say on that subject). Opinion is divided as to whether stands of this lily found very rarely growing in British hedgerows have been there since the Ice Age or just popped over someone’s garden fence and made themselves at home in our countryside. They are VERY easy to grow, although this offers no evidence to favour either theory over the other.

Here are a couple of hybrids that I have inherited from the previous owner of my garden.

Now, you know my mission is to get you growing things you might never have considered from seed, so let’s look at a few of pots of seedlings of lilies it is difficult or impossible to get hold of commercially in bulb form.

By the way, you can happily fill your garden with the thousands of hybrids you can get at the garden centre or by mail order and, barring a really serious attack of the scarlet lily beetle, which will feast on every part of your plant, they will grow well, multiply and come up year after year.

But what about something a little different, something no one else in the street has?

Perhaps Lilium pardalinum, a North American with hanging red and yellow flowers? If you’re lucky you might find it in limited numbers at one of a handful of specialist UK nurseries (all manner of environmental laws exist to prevent the importation of infected plant material from abroad, although I have purchased from other EU countries with no problem. Vendors in non-EU countries will demand you pay for them to provide a phytosanitary (literally “clean cells”) certificate to prove to customs that each plant/bulb is disease and pest free. Last time I checked they cost £70 per plant, so something for the serious collector only).

Seed, however, does not carry viruses and any new stock raised from seed will be, at least at the start of its little life, perfectly healthy. So I can, and do, legally obtain seed from Asia, Chile, South Africa, the US, Australia, the Caucasus and anywhere else that takes my fancy. Online auction sites (not just THAT one, there are others, particularly one based in South Africa) are a great source.

Raising lilies from seed is not a complicated business. Species are divided into various groups according to their method of germination (some send up a leaf first, some make a bulblet first and show no sign of life above ground in their first season). There are terms for this but I’ve never got my head round them so I’m not going to ask you to either.

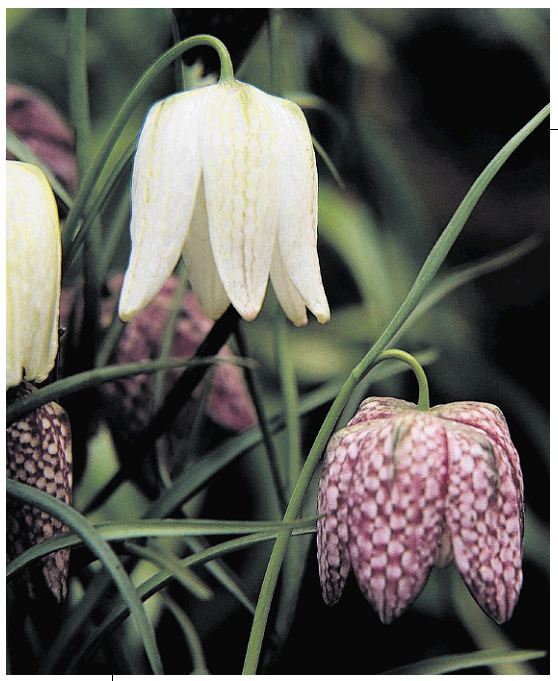

It just so happens that this week I’ve been sowing almighty quantities of our native snake’s head fritillary, Fritillaria meleagris, in the hope that I can pepper my woodland garden with groups of these curious beauties with their nodding, chequered heads that look very little like the aforementioned snake. As Fritillaria are in the same family as lilies, the Liliacae, raising them from seed requires exactly the same technique.

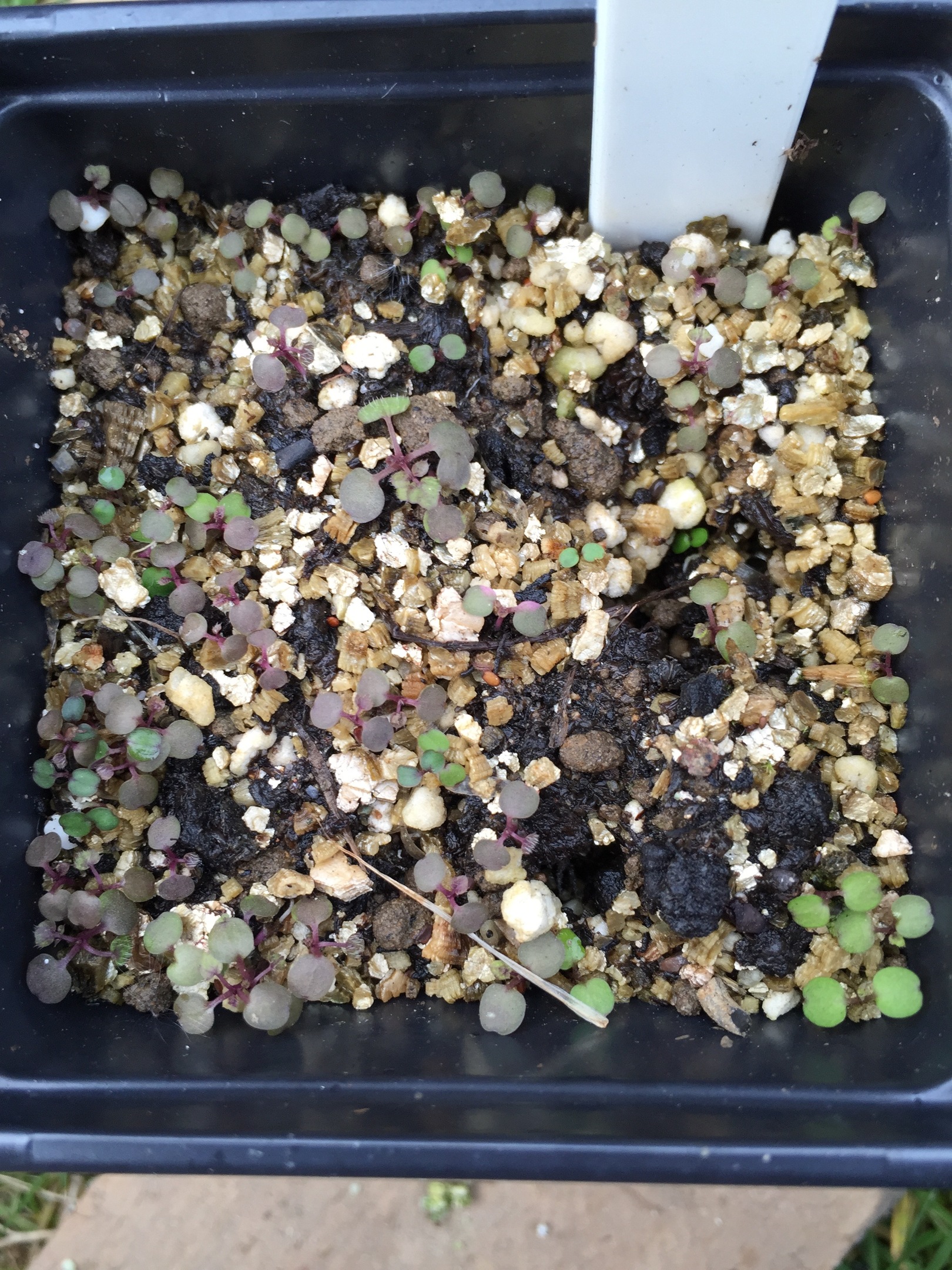

I’m raising these in industrial quantities so I used professional seed trays acquired second-hand from a nursery.

Next you need your sowing medium. John Innes seed compost or No 1 is best as it has the texture to suit exploring rootlets without having too much in the way of nutrients to scare them. The seedlings will be in here for two years as they establish so remember you will have to start feeding as time goes on.

When sowing in these quantities it’s not really practical to push each seed around the surface of the compost to give it its own space; it’s more a case of sprinkle and hope. Some will be too close together but they’ll just have to learn to get on with each other.

Now you want to cover the seeds. My preferred option for almost all seed is to use a layer of fine grit for this. It anchors the seeds to the growing medium, allowing them contact with moisture, but lets in light, which, as a general rule, seeds need to germinate.

Finally, select a shaded spot outside where the trays or pots can spend the winter unmolested as the seeds, both frits and lilies, need a winter chill before they will pop up in spring.

The above-mentioned friendly neighbourhood cat found it’s way into one of my cold frames full of sown seeds of all manner of tasty treats from Azalea hybrids to Zephyranthes (literally A-Z) and made this rather heart-breaking mess.

Some of larger seeds can be rescued with the help of a colander and some tweezers but others will just have to be written off. Some came as a one-off opportunity from a contact in Greece so this really is gutting. Which, of course, is not something I would want to do to Tiddles here, whom I caught sauntering along the garden wall looking for all the world as if it had nothing to do with him.

But to cheerier matters.

In flower at the moment are a few of my Impatiens, including the legendary (in planty circles) I. namchabarwensis, discovered by two intrepid, modern-day plant hunters, Yuan Yong-Ming and Ge Xue-Jun, in a remote part of Tibet in the barely-explored Namcha Barwa Canyon. Noted for being the world’s deepest canyon, it was hiding a little blue wonder, growing at an altitude of 930m in a very limited area of the uninhabited Tsangpo gorge, a dramatic landscape twice as deep as the Grand Canyon.

With less interesting backstories but just as enchanting are these two, to be followed in the coming weeks, I hope, by another three or four species of what you might know as Busy Lizzies.

What else … there’s this honeysuckle, or Lonicera to give it its Sunday name, which I’m pretty sure arrived wrongly labelled as L. Henryi “Copper Beauty”. Either that or it’s just been badly named, it’s just not very coppery. Pretty though.

Now this next fella is a real curio. It was collected in China and, as far as we can tell, is a Lobelia, the same genus as those blue, white or pink trailing flowers so beloved of hanging basket and window box enthusiasts. It has been given the name “aff. montana GEY125”. The “aff” means simply that it has an affinity to a species called Lobelia montana but no one is quite sure whether it actually is to this species. The GEY125 bit is simply a number assigned to it by the plant collector so that it can be identified while the boffins at Kew or wherever decide what we want to call it.

This here is one of the bluest of blues in the plant world. It out-blues even the bluest strains of Meconopsis, the stunning Himalayan blue poppy. It’s Salvia patens, a close relative of Salvia officinalis, which combines very well with onions to make stuffing, being as it is sage. That’s S. officialis you should be eating, not S. patens. This plant comes really easily from cuttings so you can give one to all your friends. But not too many, we want to keep it our little secret, OK?

To compliment, or perhaps clash horribly with, the above I am growing the bright scarlet Salvia coccinea from seed.

Now, here’s an example of my hypocrisy and inability to stick to my own rules. Last November I sowed seeds of Gunnera manicata, which need a bit of warmth to germinate, so I shoved them in the heated propagator unit at the recommended 15C. And nothing happened. For ages.

When summer came along I just moved the pot outside with a heap of other refuseniks so that nature could take its course. Still nothing. I was beginning to think I was going to fail with this enormous Brazilian wonder with leaves big enough to stand under in the rain and stems so spiky a butcher could use them for knives. It will, in moist enough conditions, reach 3 metres by 3 metres and, should be hardy in Scotland, given a few precautions. It thrives at Edinburgh’s Botanical Gardens. The first frosts will turn those massive leaves to mush pretty quickly so, wearing thick gloves, I’m not joking about the spikes, remove any dead material and cover the crown of the plant with a good pile of straw (easy to come by in Alford, the home of the Aberdeen Angus cattle breed, maybe not so easy in Aberdeen itself) or wrap in garden fleece and make sure either of these is well secured. Next spring you should see new growth and, after the worst of the winter has passed, you can unwrap the bandages.

ANYWAY … I bought a young plant in a 9cm pot and it has fairly taken off. That’s a packet of fags down there to give you a sense of scale. I would have used a pound coin but it would have been invisible and a London bus or Nelson’s Column were just impractical. So if my mum’s reading this in Heaven, I was just looking after them for a friend, OK?

Of course, you guessed the next bit. A few days ago I was going over some slightly abandoned pots and found this:

I’ll leave you with another, possibly even more remarkable, example of the hybridiser’s art. Whoever came up with the idea of crossing our native foxglove with Isoplexis canariensis (from the Canary Islands, we’re getting the hang of this now) was struck by a flash of genius.

He or she took this:

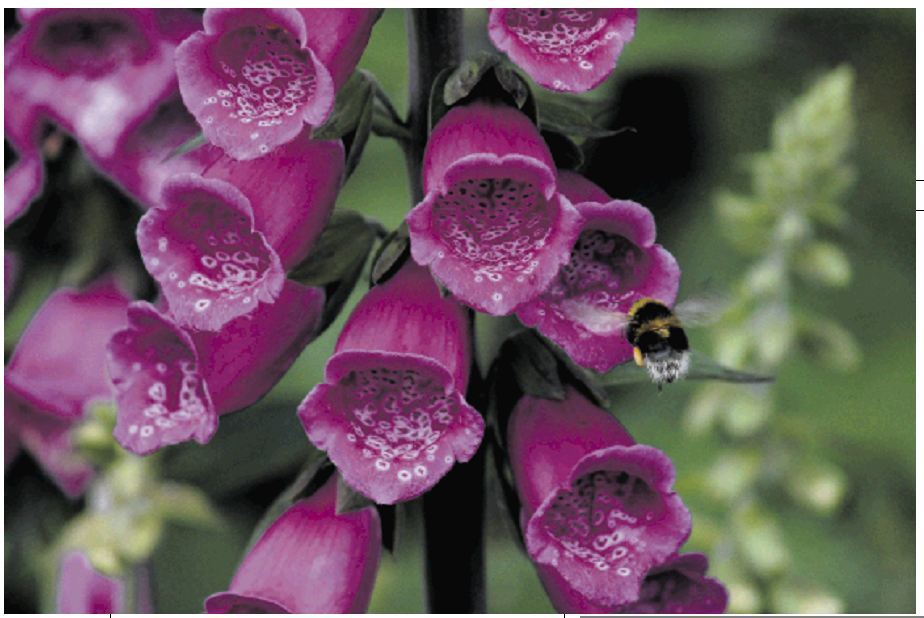

Crossed it with this:

And came up with Digitalis “Illumination Pink”. So good they named it Plant of the Year 2012.

That’s it for now. Next time I might take a look at the ginger family, the brilliantly named Zingiberacae, if enough of them are getting their flowering groove on (the Hedychiums have noticed it’s September).

And you thought ginger was all about the biscuits!