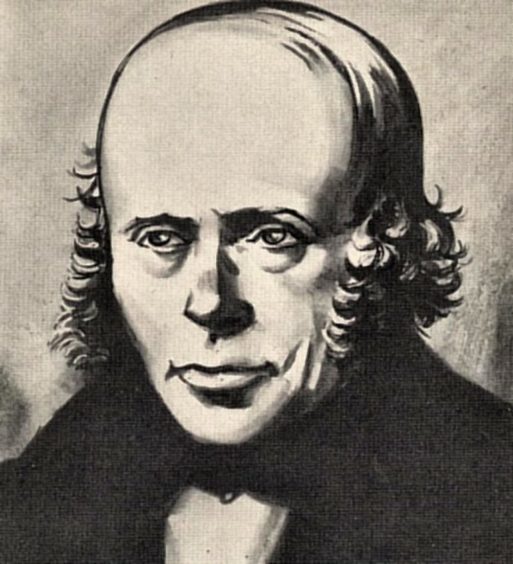

A north-east family found a photograph of their great-great-grandfather, the pioneering inventor Robert Davidson, in an envelope in a drawer at their home.

The sepia-tinged image dates back almost 150 years and features the man who designed the world’s first electric vehicle and put it and other artefacts on public exhibition in Aberdeen’s Union Street in October 1840.

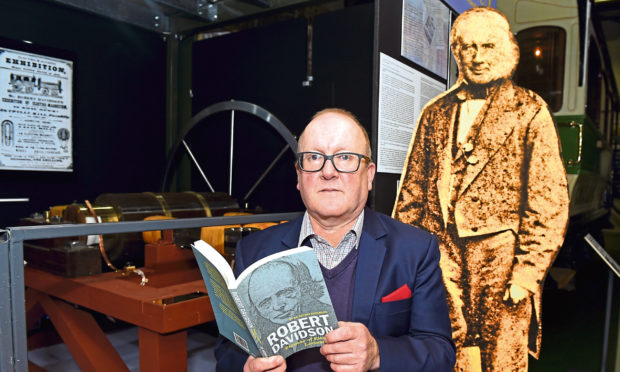

Granite City pioneer Davidson’s achievements have been highlighted by Grampian Transport Museum at Alford, and a new book by Dr Antony Anderson tells the story of the enigmatic Scot who preferred to work on his inventions rather than patent and profit from them.

Davidson’s peripatetic life from 1804 to 1894, stretching from the Battle of Trafalgar to the Boer War, spanned a period of unprecedented change, heralding the arrival of such items as the steam engine, the telephone and the introduction of the electric light bulb.

And the Scot played his own pivotal part in the development of these new scientific advances. His experimental locomotive predated by decades Werner von Siemens’ electric tramway, which was unveiled at the Berlin Exhibition in 1879, and he was prescient in recognising the potential of electric cars and trains.

Automobile companies are working round the clock at the moment to create these new vehicles in a bid to reduce carbon emissions. But, almost 200 years ago, Davidson originally devised the mechanics of bringing such a plan to fruition.

It’s hardly surprising that motoring enthusiasts have been excited by the amount of new information which has emerged in recent years about the beetle-browed individual, who refused to blow his own trumpet, in the mistaken belief that his achievements would speak for themselves.

That is one of the reasons his exploits are largely unknown.

Trailblazing methods

A new book by Dr Antony Anderson, which has been published with the backing of the Grampian Transport Museum in Alford, has emphatically demonstrated that Davidson was a man who was generations ahead of his time.

Mike Ward, the curator at the museum, told your life he was very impressed with the trailblazing methods which were used by his compatriot during one of the most revolutionary periods in the history of science, technology and engineering.

He said: “Robert, the third child in a family of four boys and two girls, was the son of a shopkeeper and an Aberdeen Grammar School boy and he was encouraged to take an interest in what were viewed as the ‘useful arts’ and learn all about them.

“He soon proved himself to be an ingenious and innovative character who created superb engineering models to help him run his own business.

“He was fascinated by so many things and was one of those Victorians who kept pursuing new advances in many different fields. He was involved in crafting useful things, including the black art of making and sharpening files.

“He specialised in yeast propagation to help develop the emerging distilling industry.

“He made dyes for colouring cloth and, at one stage, even specialised in plants, so there were a lot of strings to his bow and he was a real entrepreneurial spirit. I think it’s amazing he had such an impact in so many diverse areas.

“His work in electromagnetism was ground-breaking and his name was associated with other great scientists of his time, including the world-renowned physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who spent a significant part of his life in Aberdeen.

“Basically, Davidson was somebody who wanted to make abstract things useful. He took it out of the laboratory and put it to work – and he was the first to do that.

“At an exhibition in Aberdeen in 1840, it was Davidson who first showed a working electric vehicle to the public. This was no mean feat in the mid-1800s.

“Electricity – or electromagnetism as it was called – was such a new and unknown phenomenon that science hadn’t even got as far as quantifying it.

“At that time, there were no units of electricity – no volts, amps, watts, joules or ohms as we now describe them. They just couldn’t measure it. And yet, here was Davidson in the north-east of Scotland making it move vehicles and carrying people before we had any of that understanding.”

Exhibition

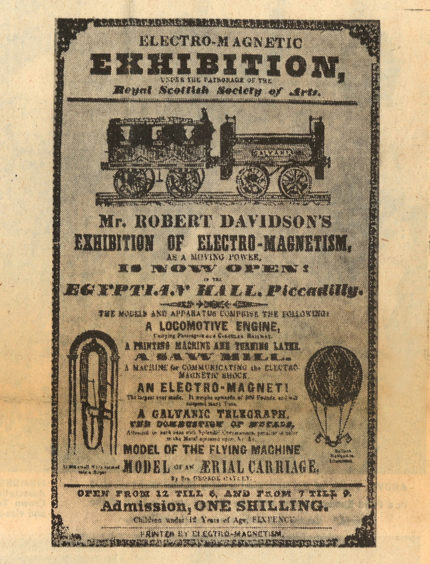

The museum has organised an exhibition which summarises Davidson’s contribution to the use of electromagnetism and, in particular, its effectiveness in relation to traction and vehicles. And it has become clear that his electric carriage – which could carry two people – was the first recorded passenger-carrying electric vehicle in history.

Dr Anderson’s book chronicles how the Scot was prepared to highlight his scientific work to the Scottish public and he organised a special exhibition at 36 Union Street in Aberdeen from October 2 1840 – which ran for three weeks – with an admission price of a shilling, which didn’t deter thousands of people from attending the event.

He was exhibiting a variety of devices, including a model of a locomotive carriage, which was sufficient to carry two people; a turning lathe; a small printing machine, organised through magnets; and a “machine for communicating electric shock, featuring the combustion of metals by electromagnetism and other phenomena”.

Many of the visitors marvelled at these artefacts and the Aberdeen Journal – the forerunner of this newspaper – was impressed by Davidson’s ideas and imagination when it reviewed the exhibition with positive words on October 23.

The report stated: “In the space of just one day (October 14), 1,100 people had the satisfaction of witnessing the collection.

“Our ingenious town man’s inventions continue to attract visitors from far and wide. Last week, they were inspected by Dr Hamel, from Russia, a gentleman well known in the scientific world, and who expressed his huge gratification with the exhibition.”

For the benefit of all

Davidson, himself, was an egalitarian fellow, who had no grand ambitions of amassing vast wealth nor profiting from his inventions.

Unlike the prolific Thomas Edison in the United States, who slapped a patent on anything and everything he created – and notoriously took credit for the work of others on several occasions – his Scottish counterpart was determined that his creations should be available to everybody who might be able to benefit from them.

He declared in the poster advertising his exhibition: “Mr Robert Davidson begs to intimate that he has, for the last three years, been engaged in a course of experiments on electromagnetism, with a view to devising means for the employment of the magnetic influence as a moving power.

“In this objective, he flatters himself that he has succeeded and he trusts the time is not too far distant when, on account of its greater cheapness and simplicity, and its perfect freedom from danger, the electromagnetic power shall have superseded steam for many or most of the purposes to which the latter power is now applied.

“Mr Davidson has declined securing to himself by patent the exclusive right to the use of this new power.

“He believes that all to whom the possession of a cheap, simple and safe substitute for steam power is an objective, should freely avail themselves of the advantages to be drawn from his invention.”

In short, money wasn’t the main motivation for this bright spark. Discovery and innovation were far more important in his world.

Full-size working replica

Mr Ward and his colleagues at the transport museum have built a model of Davidson’s 20-cell zinc iron battery and a full-size working replica of his electric engine.

It was a major undertaking to produce this device with its five-foot flywheel, but it was worth the effort, given the substantial interest that members of the public have shown.

Now, mirroring what happened 180 years ago, Davidson’s endeavours have sparked fresh curiosity, especially with the publication of Dr Anderson’s book which was, in itself, a labour of love which has taken more than half a century to be published.

Mr Ward said: “The Davidson family were, and are, very helpful and, of course, they are keen to have their illustrious ancestor better recognised.

“They passed all Davidson’s records to the National Library of Scotland, which was a masterstroke, and they had kept them safe and sound for many years.

“It was they who recalled Dr Anderson’s interest in the subject, back in the 1960s and 1970s, and they discovered he produced a manuscript, but never got round to publishing the work. At that point, those of us at GTM felt we must help him realise that ambition, both for himself and for the Davidson family.

“We fact-checked against the library material – there were masses of it – and then we proofread the work and published the book.

“It is selling very well and a second edition in the future will include more very early photographs, including the one which has just been found in the attic.”

Illustrious ancestor

Stuart Scorgie said he was delighted at finally unearthing the picture, which was taken by Ballater-based William Reevie during the 1870s.

He said: “My reaction to finding the photo was one of disbelief. My grandmother died in 1959 and passed on a few odds and ends to my father, one of which was this photo.

“He had it all this time, hidden away in an envelope in a drawer, and never once thought about mentioning it, even though we knew quite a bit about Robert Davidson in the 1970s thanks to the work of Dr Anderson.

“The photo only came to light after the book was published, because my father had just forgotten all about it.

“Robert died in 1894 – at the age of 90 – leaving a sizeable amount of money to his son, also Robert, who travelled to the United States and squandered his fortune on railways and orchards – this was a common way of investing or losing your money at the time.”

Mr Scorgie said he and his family were thrilled at the increasing amount of interest being shown in their illustrious ancestor.

He added: “In a way, things have come full circle, because electric cars will soon be the norm with people not realising that this most modern automotive phenomenon is indeed similar to the technology that was developed 180 years ago.

“I think it’s great that more people are finding out about Robert Davidson and now, I am just waiting for Elon Musk to find out and send me a shiny new Tesla!”

enigmatic inventor

Dr Anderson has posed the intriguing question of why Davidson is not more widely renowned in the city where he spent almost all of his long life.

Was he simply too self-deprecating for his own good? Or was he uninterested in the trappings of fame and the publicity which might have accompanied it?

The author says: “Aberdeen seems to have forgotten Robert Davidson. He is partly to blame for this lack of recognition, because he failed to document and publish his work.

“So we have had to pick our way, as best we can, through scattered records to piece together even the most approximate picture of the life of this enigmatic inventor.

“The Davidson story is by no means complete and there may still be material somewhere about him which is yet to be discovered. But that is what makes historical research so interesting, isn’t it?”

Robert Davidson: Pioneer Of Electric Locomotion by Dr Antony Anderson is available from most bookshops or at the Grampian Transport Museum at www.gtm.org.uk