The ice-cream Mars bar, no argument, is the best confectionary product ever.

Take it out of the freezer, let it slightly defrost for a few minutes, then bite in. Perfect.

Now, just imagine how the concept was pitched in the Mars boardroom.

“We’re going to diversify our iconic Mars bar, by freezing it and offering as an ice-cream product”. Out of a crazy idea that made no business sense the best ice-cream product, ever, was launched in 1989.

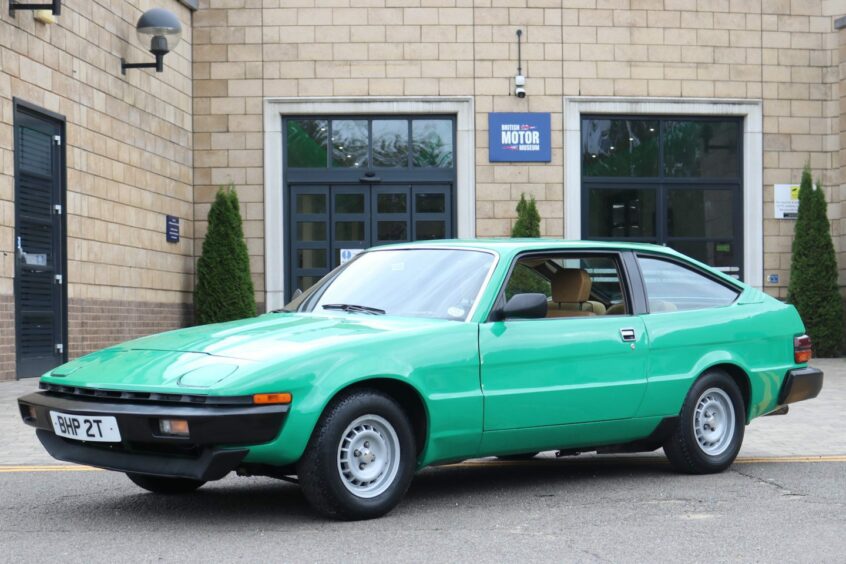

I give you the British Lamborghini Espada, with pop up headlights… the Triumph Lynx

This month I’ve been driving what should have been the motoring equivalent of the ice-cream Mars bar.

A concept, to my mind, a lot easier to sell in the boardroom. Here’s my take on the pitch: brand extension to the Triumph car range with a well sorted sportscar using in-house components, all wrapped up in a four-seater hatchback body.

“British Leyland decision makers of the 1970’s, I give you the British Lamborghini Espada, with pop up headlights… the Triumph Lynx”.

More muscle, better handling, and great style

I imagine rapturous applause after the presentation as those attending realise that this is a real competitor to the Vauxhall/Opel hatchbacks and Capri offerings, but with more muscle, better handling, and great style inside and out.

A genuine four-seater sports hatch that could attract the growing mass of middle-class buyers seeking both style and space for a family and their luggage. It’s a winner, right? Wrong.

A restart to the Lynx project

Plans for a four-seat Triumph sports had been pitched, without success, since the 1960s under the codename Lynx. In 1971 the project was re-started and paired with the upcoming TR7.

The Lynx would be its longer-wheelbase brother, taking the fight to the Capri in Europe and providing a logical range extension to the TR7/8 in the United States.

Development of the Lynx was stepped up following the start of TR7 production in September 1974, with the plan to use as many of the British Leyland (BL) components already being produced, which included the engine, gearbox and rear suspension from the Rover SD1.

Industrial relations throw a spanner in the works

The package looked very viable and, once it became clear that there was excess capacity to produce it, the BL Board gave it the go ahead for production.

The problem was that by the time that the tooling was ready to be installed into the Speke factory coincided with, quite frankly, unbelievable industrial relations problems between the workforce of the Liverpool factory and the company’s management.

It would be lazy to lay the blame solely on the BL workforce. Sure, they preferred being on picket lines rather than production lines, and yes, they had a corrosive anti-management, anti-government, and anti-work attitude, but, in their defence it was management failings that allowed the chaos to unfold.

Quality control sees a drain on customers

The 1970’s bosses at BL had as much financial know-how and communication skill as Kwarteng and Truss. BL management was out of money, consumed with in-fighting, and was responsible for producing poorly built products due to flawed and outdated production processes. Customers were being lost through a lack of quality.

As an east-end soap character might say, I’ve got “previous” with this concept. Back in 1986, having received a company car, I was able to justify a two-seater sports car as a private purchase.

The creation of a sportscar which was the envy of my peers who had bought new hot hatches

I bought an open top Triumph TR7 that had been converted with a Rover 3.5 litre engine into a TR8 by a Newcastle engineer at his home.

I then invested some of my salary with a Triumph specialist, located in a dodgy part of Gateshead, to up the power (through a Holley carburettor, Offenhauser manifold and “flexi” twin exhausts), and improve the stopping with better brakes.

Feeling right at home

The result was the creation of a sportscar which was the envy of my peers who had bought new hot hatches.

That was my Tyneside two-shed creation from 1986, so what’s the BL factory produced prototype brother car like in 2022?

Well, I felt right at home. Settling in behind the US specification steering wheel and left-hand controls, I noticed Rover SD1 door opening, and electric windows that weren’t in my old car, but overall, the feel was just the same.

Controversial styling

For a tall person you can’t beat the headroom, legroom and how the steering wheel falls to hand.

The styling of these Lynx cars was, to put it mildly, controversial. The front is pure TR 7/8, and with the pop-up lights it still looks fresh. The rear styling treatment needs more work, the lines just don’t flow. My thoughts are graft on Jaguar XJS Eventer style taillights and/or a spoiler, and all would be well.

The packaging is spot on, though, with accommodation for four normal sized humanoids. Even I can just fit in the rear.

I love the Rover V8, a unit that can be taken to 5.0 litre as TVR proved. As ever, it works well in Lynx, delivering plenty power, and for me the familiar 5-speed gearbox is a joy to use, which I did, on the road and overly large roundabouts at the entrance to the British Motor Museum.

On my early morning visit there was no other traffic, so I pushed the Lynx round these, which was very satisfying, with the car handling better than I had hoped. Ahhh, the delight of a big engine up front driving the rear wheels.

Public appetitite for the Lynx

The green Lynx I’ve been driving still lives in the British Motor Museum, the sole survivor of 18 prototypes. When the Lynx project finally died it wasn’t because it couldn’t be made; BL still had factory space and the tooling had already been ordered. No, it’s seems there was no appetite for it within the company.

But was there an appetite for the Lynx amongst the 1980’s car buying public, of which I was one? Of course there was. That’s even more obvious than making ice-cream Mars bars.

- Thanks to Cat, Hannah and Martin at the British Motor Museum, Gaydon, for their help, and where the Lynx is now back on display.

Conversation