If you love exploring Scotland’s great outdoors then you’ll fall heavily for the Faroes.

This isolated archipelago is a challenging and stimulating destination for families, couples or individuals with a sense of adventure. Only a mere hour and 15-minute flight from Scotland, visitors arrive at the edge of the world.

As the Atlantic Airways plane starts its descent passengers receive a breathtaking first impression: small, picture-postcard towns set atop vast cliff ranges with waterfalls cascading into the ocean. It’s immediately apparent that nature is a very powerful beast here.

The landscape is strangely familiar; a mix of Orkney, Shetland and Lewis with an epic dose of Glencoe thrown in for good measure. This isn’t a comfortable place, it’s a destination where your senses are heightened the minute you touch down.

The airport is situated on the island of Vágar and most tourists head for the capital of Tórshavn on the neighbouring island of Streymoy. Don’t worry about waiting for ferries, when the Faroese want to link their islands they build tunnels underwater or hack through mountains pretty swiftly, so it’s an easy 45-minute drive to some of the best hotels and restaurants the Faroes have to offer.

The islands are bare basalt rocks, jutting out of the Atlantic, with sweeping valleys sliced through by glaciers during a truly decisive ice-age.

The grandeur, power and majesty of the landscape is inescapable, and deserves to be described as awesome as it strikes genuine awe into the beholder.

Visiting the Faroes is about experiencing the wilderness and the beauty of a land that is stark, raw and captivating. It’s a photographer’s, hiker’s and birder’s dream, and if it’s said that you get four seasons in one day in Scotland then up this considerably in the Faroes and dress accordingly. Two accessible and achievable hikes are indelibly printed on my mind and encapsulate what the islands have to offer.

Parking at the small town of Saksun at the north of Streymoy grants the opportunity to walk (strictly only when the tide is out or going out) straight out to meet the Atlantic. The route is called Út á Lónna, 3km each way, and takes roughly an hour.

Heading down a gravel path, passing possibly the most free-range hardy sheep and lambs in existence, hikers follow the water to a beach and its dramatic waterfall – admittedly the Faroes aren’t short of staggering waterfalls. From there, with the wind behind us, it was an effortless power march to the Atlantic. Staring out at the water’s greyness, it became easier to grasp how truly isolated the Faroese people are, and how this has shaped their character and their innate, endless pursuit of survival through farming, hunting and fishing in the most challenging circumstances.

Retracing our steps, with the full force of the wind in our faces, it’s clear why trees and cereals don’t grow here, and why root vegetables, tucked in the warmth of the earth, are coaxed and nurtured to feed the 50,000-strong population.

The second memorable hike is along the cliffs linking the town of Tórshavn with Kirkjubøur. At 7km long it takes approximately two hours. Heading uphill, following a clear path that on wetter days is simultaneously a small waterfall, walkers are rewarded with excellent views of the neighbouring islands of Sandoy, Hestur, Koltur and Vágar before descending into Kirkjubøur which is a riveting destination in its own right.

Here stands the ruins of St Magnus Cathedral, as well as the famous farmhouse Rokstovan, one of the world’s oldest inhabited timber houses which is open for the public to explore.

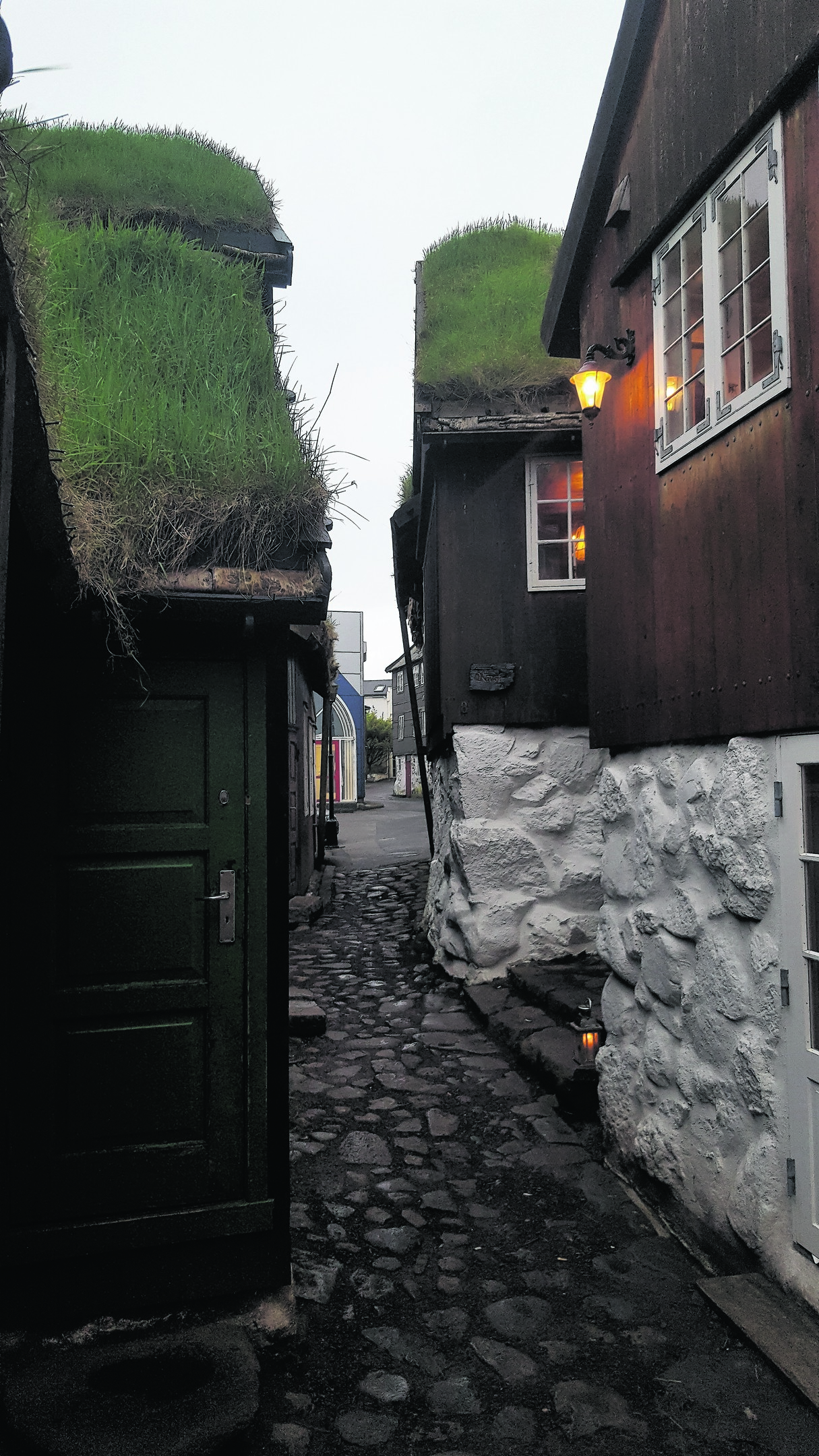

The houses in Kirkjubøur are clad in the signature black tar, with vivid red doors and window frames and the iconic insulated grass roofs.

Situated on the land of a 17th-generation farmer, sheep and Highland cows graze on the grassland, but step inside the main farmhouse to discover everyday life from days gone by.

Flotation aids created from animal guts, harpoons for whaling and ropes for catching wild birds on clifftops festoon the walls.

The ocean plays such a pivotal role in Faroese modern life, heritage and culture that taking to the water is strongly recommended.

By heading to Vestmanna on the west coast of Streymoy it’s possible to grab lunch at the local visitor centre before setting sail with www.puffin.fo cruises. Rock formations, sea stacks, caves, birdlife and the most precarious grazing lambs are discussed in both Faroese and English by the skilled skipper who navigates narrow channels and caves to bring visitors epic sights. Back onshore, those with a relatively strong temperament can visit the quite graphic museum of Saga.

It packs no punches about Faroese history, from the early Irish settlers to violent pirates and Vikings, it portrays events with a frankness that it usually glossed over by modern institutions.

From decapitations, hangings, raids, violence and drownings, it conveys history with acutely lifelike waxworks. Its upfront depictions are in some ways refreshing, and seem to tie in with the Faroese attitude of telling things as they are, but it’s probably not suitable for young children.

Other indoor activities include the National Art Gallery in Torshavn. With a permanent collection of renowned Faroese artists visitors get an insight into Samuel Joensen-Mikines who put Faroese art on the map; Ingálvur av Reyni who gained an international reputation; and the impressionism of Ruth Smith. Immediately adjacent to the gallery is the National Forest, planted with a certain optimism by the officials, and peppered throughout the woodland are striking sculptures by Hans Pauli Olsen.

His work is found across the Faroe islands, his most distinctive perhaps being the Seal Woman or Selkie statue at Mikladalur on Kalsoy – a folklore familiar to many Scottish islanders.

Eating local produce gives further insight into the Faroese way of life. Some farmers are diversifying into home dining experiences, called ‘heimablídni’, such as the one offered by Anna and Óli.

Welcomed into their dining room, with jaw-dropping views, we sampled cured lamb, salted herring, beef meatballs, followed by rhubarb cake, washed down with beer from the local Okkara brewery.

More centrally, in one picturesque street in Tórshavn, Barbara Fish House dishes up huge horse mussels and sumptuous salted cod; Áaranova’s slow-cooked lamb, cooked for 12 hours, flakes off the bone; and Ræst serves up traditional fermented food which is air-dried with a potent, distinctive flavour that is the epitome of Faroese home cooking and heritage.

For fine diners, KOKS restaurant in Kirkjubóur has a Michelin star. And for dining al fresco try Frída’s sea views at Klaksvik, or coffee by the quayside at Tórshavn’s Kaffihúsi.

From the food to the landscape, the weather and the history, the Faroes is an assault on the senses in a good way. And on a sunny day the beauty of its wilderness turns into paradise.