Hebron, or Al Khalil as it’s known in Arabic, is a city in the southern West Bank.

While other Palestinian cities in the West Bank are under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authorities (PA), Hebron is the exception and is divided into two sectors. H1 is by far the largest sector and is controlled by the PA.

H2 and the remaining 20% of the city is run by the Israelis. Astonishingly, around 30,000 Palestinians live in the Israeli-controlled sector, yet only a tiny settlement of up to 1,000 Jews live here, under constant IDF protection.

Hebron is famous for containing the traditional burial site of the biblical Matriarchs and Patriarchs. Like everything else here, it is divided, one section for Muslims, one for Jews. Sadly, Hebron’s history is soaked in blood. Two examples – In 1991, a Palestinian sniper shot dead a 10-month-old Jewish baby in its pram. In February 1994, Jewish settler Baruch Goldstein opened fire on unarmed Muslims praying in Ibrahimi Mosque. He killed 29 of them. This act led to the closing of Shuhada Street and the final division of Hebron in 1997. Subsequently, there are huge curfews and restrictions on the movement of Palestinians.

The bus from Bethlehem dropped me off in Hebron city centre and I walked the poor, yet busy, polluted and dirty streets towards the divided old town. The roads are clogged with many old cars and minibuses which belch out fumes as they all toot their horns at each other. Yet, for one man sat outside on waste ground, nothing was going to distract his ritual of reading his morning paper. I actually stood and watched him for a whole minute. I love this photo; totally engrossed in his paper, he was taking no notice of the chaos all around him.

Soon, I came face to face with the checkpoint that blocks the entrance to H2. Apart from visiting foreigners, only the Jewish settlers and certain Palestinians with permission can enter.

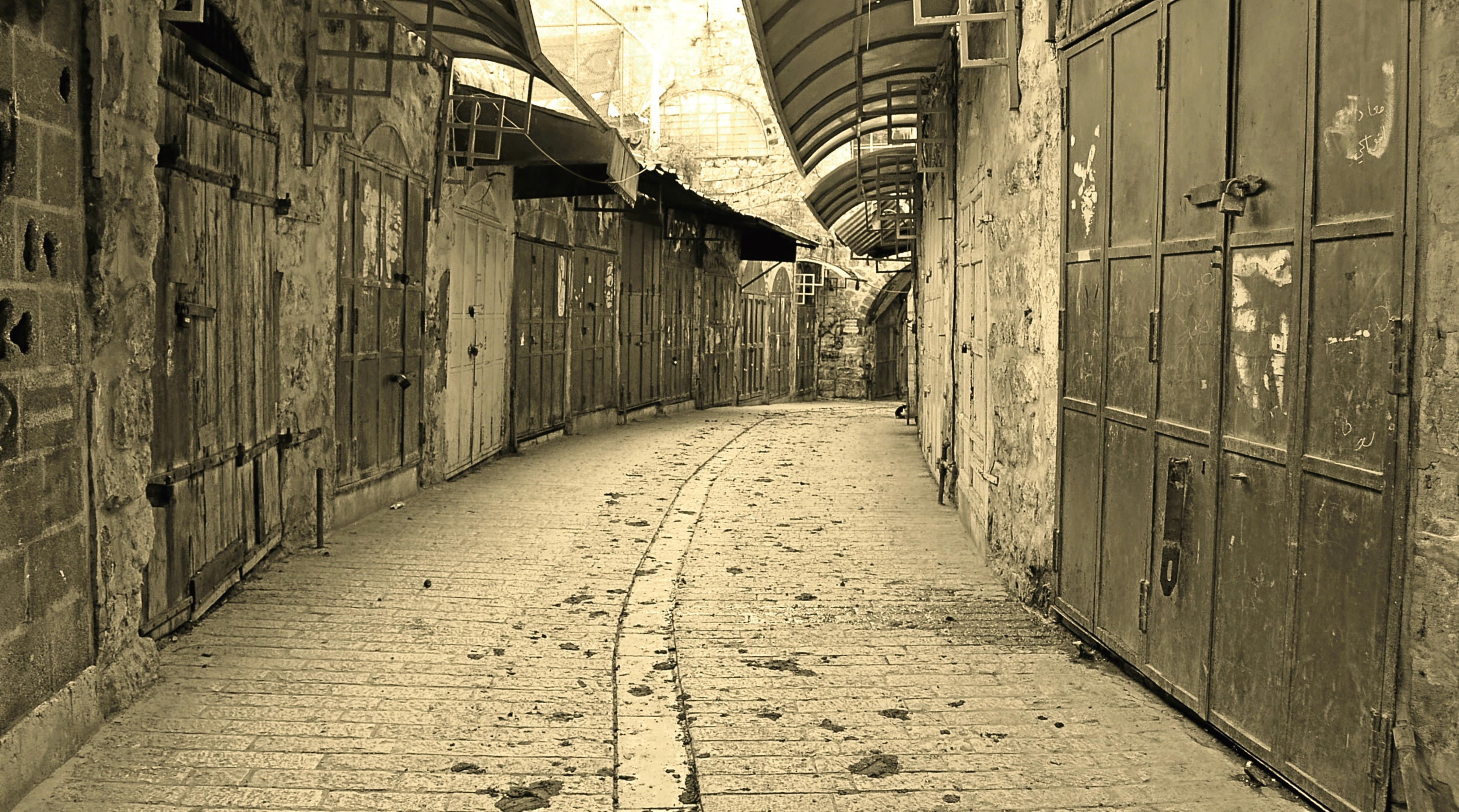

After passport checks and going through metal detectors, I stepped into H2. The difference from the ramshackle streets of the Palestinian controlled side? Worlds apart. Deathly quiet and deserted. Most shops all shut for years, it was like a scene from a movie, a ghost town.

I walked for maybe 100 metres and was approached by four heavily armed Israeli soldiers, who wanted another document check. However, as soon as they saw my official Israeli government press card, they didn’t even ask to see my passport or visa.

I’ve been wearing my stab and bullet proof vest most days while here. Not every day, I mean not if I pop down to the shops in Bethlehem to buy some bread. But I always wear it when around the checkpoints and always in Jerusalem on Fridays after prayers where most stabbing and shooting violence takes place.

I had my vest on that day in Hebron. I always have to take it off at checkpoints as it beeps like crazy going through metal detectors. Nothing illegal about wearing one, but it certainly raises eyebrows. IDF soldiers are on constant alert for stabbings, guns and suicide attacks.

The soldiers looked at my vest with suspicion, because it really could be mistaken at first glance for a suicide belt. I explained what it was. It was given the once over and one of them said “Good idea” as he handed back my press card with a smile.

I continued walking the near-empty streets – streets I’m told that even the Palestinian residents who live under Israeli control are not allowed to walk down. Only Jews and foreigners. There’s a unique feeling in the H2 sector of Hebron. Almost an oasis of calm, or maybe a sense of something’s “not right”. Very strange feeling indeed.

An hour later, I crossed through another checkpoint and was back in the Palestinian side. The livelihood of many Palestinians was destroyed when Shuhada Street was closed and Hebron divided. The few souvenir shops left had no customers, most tourist have been frightened off over the past few years.

It was coffee time. I found a classic old dirty coffee shop and ordered an Arabic coffee. I never pay more than two shekels from such places. The owner tried to charge me five, so I had a good banter with him and only paid two, before taking my coffee outside to a small rickety table. A guy came over, he talked basic English so we chatted about life. He then asked me how much I paid for my coffee. I laughed and explained the story, just as the shop owner came outside.

My new friend proceeded to scold the shop owner; it wasn’t an angry scene, good crack actually, and we all laughed. He then leaned in and in a hushed voice said: “Arab, no good.”

“But you’re an Arab,” I replied.

“Yes, but many no good, they want to take money from all. No good. Israeli good,” he said pointing over towards the Jewish sector. “My sister she now in America, good life. Here, life no good. I want Israeli passport. I want to live there. Arab no good, no good,” he kept repeating.

I walked on and came across a street where the locals were trying to lay a new sewage system. I stopped and chatted with a group of young men. Friendly enough, the conversation soon turned to the day-to-day situation they find themselves in. You know, it’s simply not true that all Palestinians hate Israel, the US and Britain. A growing number I speak to wish that they were Israeli citizens living on the other side of the divide.

“What do you think about Trump?” I asked

“Trump good!” said the man.

“Really? But what about him acknowledging that Jerusalem is the capital of Israel?”

It was explained to me by the group that basically at least Trump did what he said he was going to do. They also explained that because there’s been stalemate for years over Jerusalem, and that there will probably never be a two-state solution, that maybe the process of peace can move on. To what, they didn’t know though.

I found their views surprisingly open minded. You get precious little of that here. It’s usually very tribal.

That evening, back in Bethlehem, sitting outside my friend Adel’s shop, we discussed the topics of the day. His favourite line in previous years was: “There will never be peace in the land of peace.” Now, he chooses to use the following line: “Crazy people, crazy place, crazy politics.”

The city of Hebron may well be divided, but it’s nothing compared to what I was about to experience. Three words that invoke fear and shock the world over – The Gaza Strip.

No one but no one can just walk into Gaza. Written permission must first be sought from the Israeli authorities. The applicant must be involved in official humanitarian aid relief or work for, say, the UN. Even diplomats need permission. Applications can take months and more often than not, the result is refusal.

However, being in possession of an official Israeli government press card allows you the unique right to enter and leave Gaza as you please. The advice though, from nearly all concerned, is not to go.

I had done my homework and most importantly had been introduced to a fixer inside Gaza, with whom I had discussed my desires and my concerns on the phone. I was assured by friends in the West Bank that they knew him and that he was trustworthy.

Completely blocked off from the entire world and run by militant fundamentalist group Hamas, whose aim is the destruction of Israel, Gaza is also a base for Islamic jihad and is seen as one of the most dangerous places on Earth…

NEXT WEEK: Clearing immense security and walking into the Gaza Strip