Do Italians really have the best way of life? Try living like a local on a lemon farm in Southern Italy

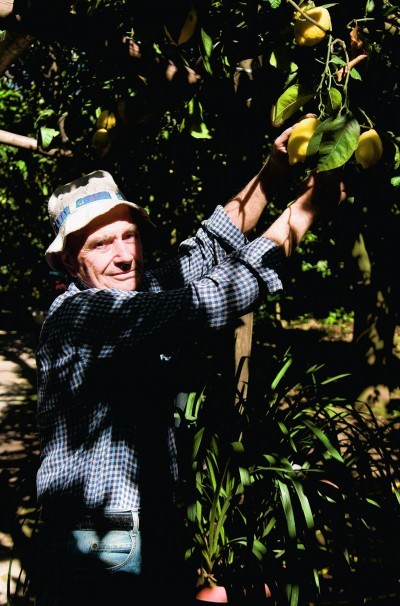

Using the same care and attention a jeweller might employ to handle precious stones, 68-year-old farmer Peppino Nunziata examines the plump, waxy lemons hanging from wooden pergolas in his 10,000 square metre garden.

“Lemons are very delicate, so they need a lot of looking after,” he tells me, after deciding this particular bunch are not yet ready to be picked.

Every day, from 6.30am, Peppino works in his garden, preparing for a marathon seven harvests, which produce an impressive 2,500kg of lemons per year.

Sadly, though, these fragrant, golden gems are no longer the high value commodity they once were; at one time Sorrento lemons were a lucrative export, but today the price is much lower.

In order to keep their business going and preserve an important part of the region’s history, Peppino and his family have been forced to diversify, opening their property up to tourists as an agriturismo – a working farm where guests are literally granted a taste of local life, with many home-grown products served at the dinner table.

The Italian government set up the concept in the 1980s, to give farmers a secondary source of income, thus maintaining the existence of farms and stopping a mass exodus of people from the countryside.

Tour operator G Adventures are now using the Nunziatas’ Il Giardino di Vigliano property in their ‘Local Living’ programme, giving tourists the opportunity to enjoy grass-roots southern Italian hospitality.

Set in the hills above Sorrento, with views of the island of Capri and a coastline dotted with umbrella pines, it’s hard to imagine that life here is ever hard graft.

As I walk through a shady tunnel of lemon and mandarin trees, the smell of citrus fruits sending me into a euphoric headspin, the thought of lemons served at breakfast (in jams), lunch (zested on pizzas) and dinner (slices served raw, dusted with sugar, as a dessert) seems very appealing.

Owned by the Nunziato family for four generations, the garden was first planted in the 17th century. Ida, Peppino’s wife, tells me that lemon production in this region was started by the Jesuits in the 16th century, although the fruit was popular as far back as Roman times.

Now, most of the lemons the family produce are sold to a limoncello factory in Capri, one of the first places to bottle the syrupy, sweet digestif 20 years ago.

Sat on the terrace of the 15th century stone farmhouse, I’m given instruction on how to properly savour a shot of the drink, which I’ve always (apparently mistakenly) served straight from the freezer.

“Good limoncello should be cold but not freezing,” Ida explains with a matriarchal authority, revealing that while Peppino’s preserve is the garden, she very much rules the kitchen.

Once the sun has seeped into the still Gulf of Naples, leaving an afterglow of pink streaks across the horizon, we head inside for a pizza-making lesson. Using a peel – a long wooden paddle – Ida slips doughy discs into a crackling wood-fired oven.

I wonder how many days I could survive on a diet of pizza and limoncello, and conclude that I could happily keep going for some time.

We bake enough bread for a picnic lunch the following day, exploring the other side of the peninsula along Italy’s better known Amalfi coastline. Following the Walk Of The Gods hiking trail clinging to the cliff tops, we watch expensive yachts cruise the waters and marvel at the exclusive Li Galli islands, once owned by Russian ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev. This area certainly isn’t short of money – or tourists.

Finally we reach Positano, where pastel-coloured houses crowd the cliff face like pushy spectators jostling for a front row view of the water.

Baking is second nature to Italians, and during excavations of nearby Pompeii, archaeologists even unearthed carbonised bread, along with grains and BBQ grills.

The famous site is a short drive from Sorrento, and an obvious highlight for visitors to the region.

Our guide, Renato, takes us to a domus (villa), which reopened 10 days ago after being closed for a 35-year restoration.

While most crowds gravitate towards gory plaster casts of coiled of bodies, killed by asphyxiation, I’m more captivated by Pompeii’s many social spaces.

Open bars on every street corner, public baths decorated with erotic scenes, and even popular communal latrines are a reminder of what a life-loving and hedonistic society this once was. (The emperor, I’m told, actually introduced a “toilet tax” for using the latter.)

Several centuries later, Italy continues to be a sociable nation – although when I arrive in Naples, I’m pleased to discover people prefer to congregate in more salubrious places.

The gateway to Italy’s enchanting southern coastlines, the city has – quite unfairly – been tarnished with a reputation for being dirty, rundown and dangerous. But for me, the former Spanish-ruled kingdom is the beating heart of Italy.

I walk along Spaccanapoli, the street which famously splits Naples in two. Some of the tufa-brick buildings are so close, residents can even reach out and touch their neighbours.

The street is also famous for stocking Christmas decorations year-round, with artisans making miniatures for the popular Italian presepe (nativity sets). Alongside Jesus, Mary and Joseph, I’m surprised to find models of that other revered deity, Maradona, who once played for Napoli.

As I sit down for another pizza, an eccentric performer turns up on a customised Tim Burton-esque scooter to entertain diners. He’s the epitome of Naples’ offbeat, humorous charm.

I remember Ida’s advice and order my shot of limoncello chilled but not frozen. Despite my self-consciousness, sunburned shoulders and fragmented Italian, I’m confident I might just have passed for being a local.

G Adventures offer their seven-day Living Local Sorrento group tour, exploring Pompeii, Capri, the Amalfi coast, Sorrento and Naples, from £999pp. Price includes most meals, accommodation, transport and local guides (flights extra).