Something that’s been in constant use for 200 years has certainly witnessed history.

In the two centuries since the Caledonian Canal has been open, there have been numberless wars, mind-blowing technological advances, more than a billion cars and thousands of planes currently on the planet, freight now circumnavigates the world on huge container ships, and we’ve not only had moon landings, but missions to Mars, and can even see millions of light years back in time.

Thomas Telford, the architect of the canal, would be utterly amazed.

But on Caledonian Canal, the pinnacle of the 1000 or so pieces of infrastructure he built, life flowed by at a slower pace.

Not to say that it wasn’t busy.

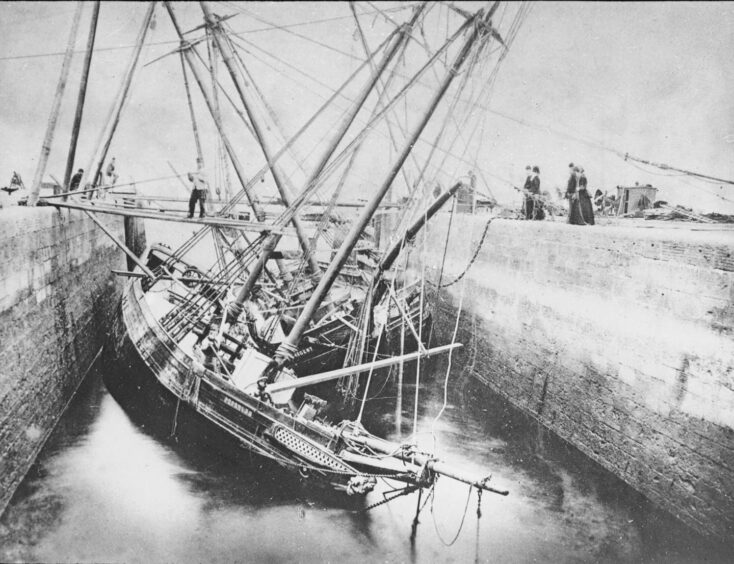

There were constant incidents and accidents to deal with, like this one on April 2, 1881.

Two schooners became jammed together when entering the sea-lock at Clachnaharry.

They became wrecked as the tide receded and soon sank.

Regent was carrying coal from Warkworth, in Northumberland, to Inverness while Progress was taking potatoes from Cromarty to Cardiff.

Three weeks later they were raised and beached about 50 yards west of the entrance to the canal where they remained.

A tourism highway

In 1873 Queen Victoria travelled on the canal aboard the steamer Gondolier, sparking an exponential growth in visitors, despite her description of waiting in the locks as ‘tedious’.

She wrote in her journal: “The Caledonian Canal is a very wonderful piece of engineering, but travelling by it is very tedious. At each lock people crowded up close to the side of the steamer… It is nervous work to steer for there is hardly a foot to spare on either side.”

Nevertheless, she had started a fashion, and the canal became a holiday destination offering steamer cruises and a chance for people to slow down and enjoy the scenery.

Paddle steamers transported goods

Paddle steamships would have bustled up and down carrying goods and livestock from the canal’s opening in 1822 until well into the 20th century.

This was a source of income for the Canal Commissioners.

For example in 1898, they saw revenue of more than £36 (£4,500 today) every three months from canal steamers bearing names such as Ethel, Cavalier, Tregan, Tartan, Handa and Maisie.

The canal was useful for conveying livestock between various towns and villages, but it can’t have been much of a money-spinner for the Commissioners.

Records held in the Highland Archive show that in the two years to April 1899, the canal steamers carried 76 cattle, 171 sheep, two bulls, 87 pigs and two lambs.

This brought in a miserly £3, five shillings and eleven pence, about £400 today.

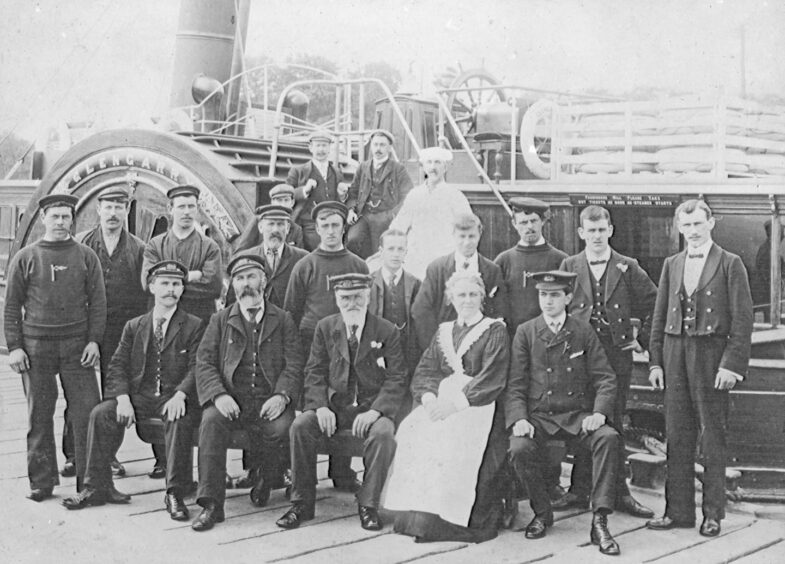

A venerable paddle steamer

First named Edinburgh Castle, later renamed Glengarry, this paddle steamer plied the length of the Caledonian Canal for 80 years.

She was built in 1844 and sold to the shipping empire of Messrs G & J Burns in 1846.

The company sold their fleet of West Highland steamships in 1851 to a partnership of David Hutcheson, his brother Alexander, and the Messrs Burns’ nephew, David MacBrayne.

This marked the germ of what would eventually become the Caledonian MacBrayne empire.

Renamed Glengarry

In the 1870s the Edinburgh Castle was lengthened, provided with saloons and given a new name – Glengarry.

The volume of passenger, cargo and mail on the Banavie to Inverness route continued to increase and a third ship had to be introduced in 1877.

From 1895 the Glengarry was placed on the Loch Ness mail run from Fort Augustus to Inverness where she remained until her last run on 29 October 1927 and was broken up three months later.

At 83 she was the oldest steamship in the world.

A busy life for the superintendent

Canal superintendents had their hands full with all sorts of challenges, very often legal.

The Highland Archive holds many documents which reveal the administrative burden borne by the superintendents.

For example, in 1889, there was a long and complex negotiation about whether the canal could supply water to the cemetery at Tomnahurich, and at what price —£2 annually considered a small charge ‘upon a prosperous company like the cemetery company.”

That year also saw complicated proposals to accommodate the railway at Corpach with a passenger station, road and canal siding.

The idea of a canal siding was abandoned, but the station opened in 1901.

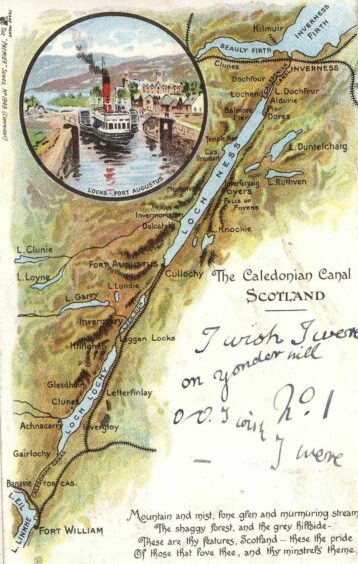

This postcard was found enclosed in the pages of the 1903 diary of 11-year-old Malcolm Blane. He manages to convey a child’s insight into the excitement of a trip on the canal.

The Amazon of their day

In 1908, paddle steamers Ethel and Cavalier were still on the go, ferrying all sorts of goods up and down the canal, a bit like the Amazon of their day.

The Highland Archive Centre in Inverness has records for timber, meal, paper, hay, bread, tea, sugar, oats potatoes, soap, ironmongery, cement and cask stout being transported along the canals.

Not to mention a barrel of apples, destined for ‘the Sanatorium’ that November.

World wars

The World Wars brought change, but in the case of the canal some of that was positive – shipping was once again under threat and having an inland passage from coast to coast was a benefit.

To some extent the canal had come full circle and was even used by submarines during the First World War.

The 20th century progressed

As the 20th century progressed the canal’s management was handed over to the Ministry of Transport before moving on to be the responsibility of the British Transport Commission and then British Waterways Board who oversaw a substantial period of modernisation in which the locks became mechanised, making the journey both quicker and smoother.

In the 21st century, the Caledonian Canal continues to be a popular and well-used part of the Highland landscape, just as it has been for 200 years.

The next 200 years

Scottish Canals’ heritage officer Chris O Connell sees a bright next 200 years ahead for Telford’s great work, including greener and more efficient machinery to operate the locks.

He said: “We’ll undoubtedly have to adapt and become more resilient to climate change, that is going to affect the infrastructure and I suspect that’s going to be a real driver for innovation.

“It’s hard to say what the next big thing is going to be, but the canals have proved to be adaptive and resilient over the past 200 years, so this can be harnessed to see them through the next two centuries.”

With thanks to High Life Highland’s Highland Archive Centre.

Read more:

Caledonian Canal 200th anniversary: Much more than just a waterway

Caledonian Canal 200th anniversary: Highland infrastructure as big as HS2 and built by hand

Conversation