“Spot the artwork,” says my guide, her finger picking out an overlooked alley on the fringes of Glasgow’s Merchant City. I hesitate: surely she doesn’t mean the graffitied portrait of the rasta smoking a joint? Perhaps the small mound of bricks topped with a fraying bin bag? What is art nowadays, anyway?

And then I spot it, a vertical signboard, black against a faded grey building, displaying six white capital letters in mirror image: “EMPIRE”. It calls up vague memories of a similar sign in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, or the Merchant City’s associations with the slave trade. “It doesn’t belong to anything,” confirms the guide. “It’s a Douglas Gordon installation.”

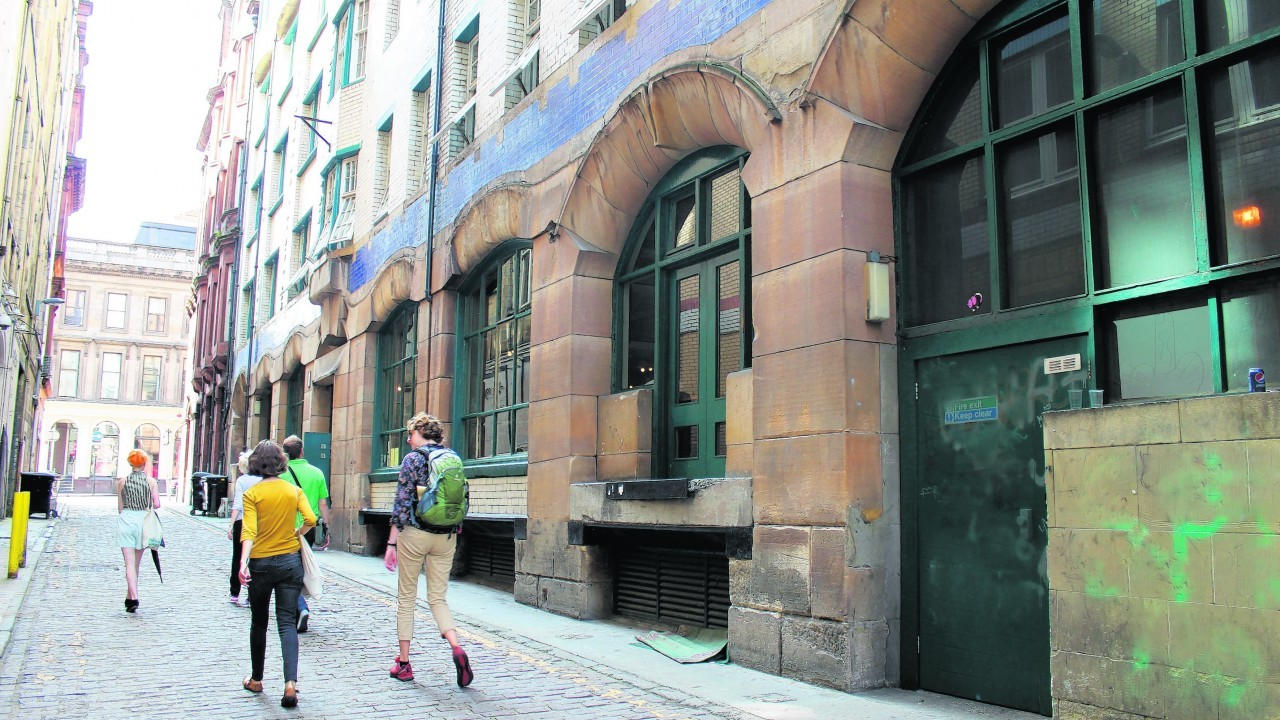

Like the trademark red sandstone of its buildings, public art colours the streets of Glasgow. Some of it is made by established names like Gordon, the irreverent Glaswegian video artist (and, indeed, Hitchcock fanatic); some, such as the remarkable murals that dot Mitchell Street, is the work of amateurs.

Some of it is beautiful, some bracingly crude – see the traffic cone that clings to the Duke of Wellington’s head on the statue outside the Gallery of Modern Art. Some of it is on full display, while some – like the “EMPIRE” sign – needs to be sought out.

But all of it points to one thing: a brilliantly creative expression in a city containing Europe’s largest collection of civic art.

This is important, because it counters the tired stereotypes about Glasgow so beloved of the media: images of a crime-ridden, hard-drinking cultural wasteland.

In cinema, its streets generally serve as a backdrop to kitchen-sink drama or noir intrigue. Decades after the demise of the city’s industrial base, it sometimes seems as if the rest of the world is set on denying Glasgow any hope for the future.

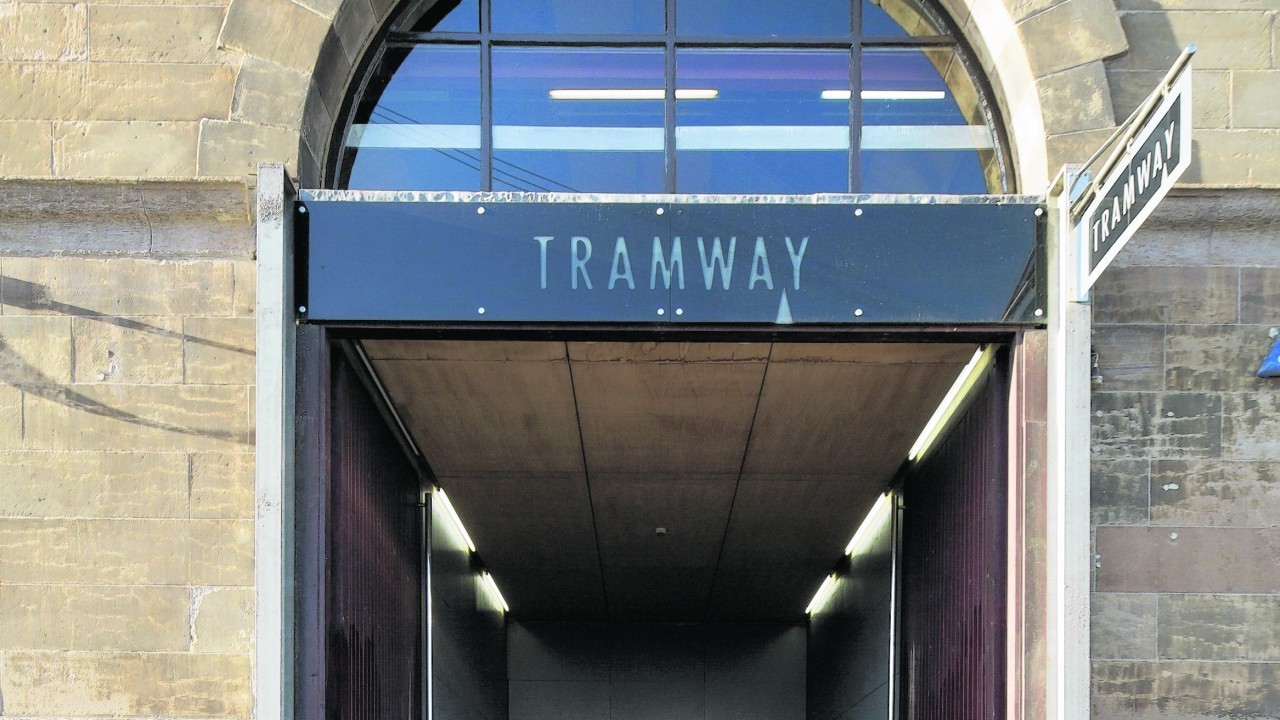

The arrival of the Turner Prize, that great promoter of artistic talent and provoker of public outrage, may mark a turning point. Whatever you think of the prize, which this year is hosted by the Tramway arts centre, there’s no denying its star power. Indeed, its judges have been doing more than anyone else to put Glasgow on the cultural map – artists based in the city make the shortlist of four almost every year, and routinely win (Gordon was awarded the gong in 1996). Given that Glasgow only accounts for 3.5% of the UK’s population, this is a remarkable feat.

To understand it, one might start with a visit to the Glasgow School of Art. Spreading out over one of the city’s signature drumlin hills, its complex of studios and research centres draws in talent from across the world, and consistently churns out successful artists – including four of the last 10 Turner Prize winners.

Pride in their city is palpable among the students, who run insightful walking tours of its art and architecture (such as the one that took me past the “EMPIRE” sign). Crucially, cheap rents encourage many to stay in the city after their studies, ensuring a fruitful mingling of recent graduates and high-profile alumni on the scene.

“That’s the thing: we all know each other,” says Calum Matheson, a painter and ex-GSA student now based in the West End’s SWG3 studios. “The other day, a friend of mine was putting on an exhibition in her flat. Ex-Turner nominee Spartacus Chetwynd, who lives upstairs, came down with her mates to have a look. That wouldn’t happen in London.”

As we talk, Matheson shows me around the sprawling studios, which house some 120 artists in a former warehouse and under railway arches (leased from Network Rail for £1 a year). A bustling bag makers’ atelier neighbours a graphic design studio, its walls adorned with literary quotes in esoteric typefaces.

Next door, the 120-capacity Poetry Club, created by pop-obsessed visual artist and – you guessed it – former Turner nominee Jim Lambie, puts on regular spoken word and club nights. “All the Glasgow old guard come back to play here,” Matheson tells me. “Hudson Mohawke, Rustie… Even Primal Scream – those guys barely fit on the stage…”

With its whitewashed cement walls and bared ventilation, SWG3 embodies the spirit of the new Glasgow; the transition in its stock-in-trade, so to speak, from industry to culture.

This story of regeneration is playing out across the city, from the scuzzy-chic West End to the spirited Speirs Lock district. Here, on the bank of the Forth and Clyde Canal, sits The Glue Factory. Its labyrinthine venue encompasses studios, galleries and performance spaces. Visual art is combined with music, sometimes in one installation. In the first gallery I’m greeted by a puppet parade of headless army drummers who mechanically beat their instruments at intervals.

Like SWG3, The Glue Factory has close ties to the GSA. And like SWG3, it makes an aesthetic virtue of its rusty furnishings and crumbling industrial infrastructure.

“I think 1990 was the turning point,” suggests one of the venue’s student volunteers, referring to the year in which Glasgow was designated the European Capital of Culture. The groundwork had already begun in the late Eighties, with the opening of landmark centres such as the cavernous Tramway, and the Glasgow Sculpture Studios, which faces The Glue Factory across the canal. But the people I speak to agree that the activities of 1990 gave the arts scene a much-needed confidence boost.

In the years since, cultural venues – mainstream, pop-up, big and small alike – have proliferated, and the number of live performances in the city has roughly doubled.

And now those decades of expansion are crowned by the dubious honour of hosting the Turner Prize. Opinions on this year’s shortlist vary widely – for what it’s worth, I wasn’t convinced by some of the sophomoric conceptual pieces on display.

But in a rare year with no Glaswegian nominees, the prize can be expected to plug Glasgow in a different way. It has thrown the city’s cultural scene into the limelight, renewing local interest in its museums, drawing tourists to its studios and galleries, and so raising the platform for a new generation of artists. Glasgow the industrial powerhouse is dead. But Glasgow the creative hub, born alongside that new generation, has come of age.

:: Alex Dudok de Wit was a guest of the Glasgow City Marketing Bureau (peoplemakeglasgow.com). The Turner Prize exhibition will be on display at Tramway (www.tramway.org) until January 17. Entrance is free.